American Christians may think of Africa most often as a mission field, but the continent now plays a prominent role in global politics too.

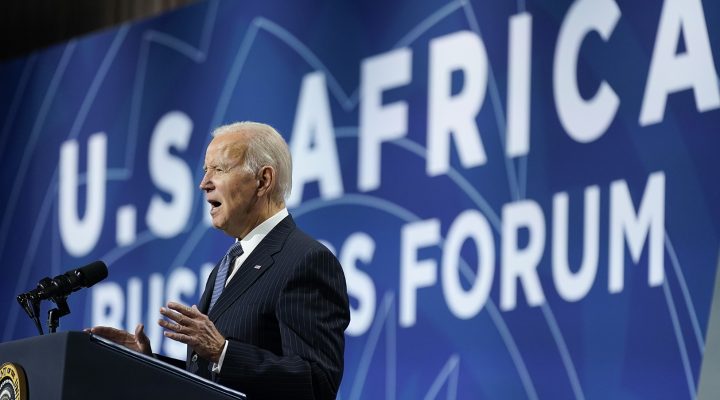

“Look, this forum is about building connections. It’s about closing deals. And above all, it’s about the future, our shared future,” U.S. President Joe Biden said at a U.S.-Africa business forum held in mid-December in Washington, D.C.

“We’ve known for a long time that Africa’s success and prosperity is essential to ensuring a better future for all of us, not just for Africa,” Biden said, later adding: “When Africa succeeds, the United States succeeds; quite frankly, the whole world succeeds as well.”

At that event, Biden spoke about U.S. financial support for Africa and pledged to do even more.

“Today, I’m announcing that the U.S. International Development Finance Corp. is investing nearly $370 million in new projects: $100 million to increase the reliable clean energy for millions of people in Sub-Saharan Africa; $20 million to provide financing for fertilizer to help smallholder farmers, particularly women farmers, increase the yields of their crops; $10 million to support small- and medium-sized enterprises that help bring clean drinking water to communities all across the continent,” he said.

U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris conducts a roundtable of female entrepreneurs to discuss economic empowerment, inclusion, and leadership in Accra, Ghana, Wednesday March 29, 2023. Harris is on a seven-day African visit that will also take her to Tanzania and Zambia. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Three months later, Biden’s vice president, Kamala Harris, traveled to Africa for a weeklong trip to Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia. During that trip, she announced a $100 million assistance for Ghana, Guinea, Benin Republic, Cote d’Ivoire and Togo, all West African countries.

“The United States will remain a steadfast partner for progress,” the vice president said. “I am more optimistic than I have ever been about the future and the future of the continent of Africa.”

Such talk may be familiar to U.S. churchgoers, because Africa is one of the most common destinations for mission trips and missions partnerships — from building water wells, to medical missions and schools and social services, along with evangelism.

On the global scene, Africa — a continent comprised of many poor and developing countries — now plays an increasingly important role in the battle for world prominence between the U.S., China and Africa.

Over the past decades, both China and Russia have made serious incursions into Africa with the aim of upstaging the U.S., and some analysts believe the U.S. now lags behind the duo in influence on the continent.

“Africa has been crucial to China’s foreign policy since the end of the Chinese civil war in 1947.”

“Africa has been crucial to China’s foreign policy since the end of the Chinese civil war in 1947,” according to a February 2023 report by Chatham House. “China supported several African liberation movements during the Cold War, and for every year since 1950 bar one, the foreign minister of the People’s Republic of China has first visited an African country.

Further, the report states: “China’s new foreign minister Qin Gang visited five African countries and the African Union in January 2023. Wang Yi, the former foreign minister, visited 48 African countries, and premier Xi Jinping undertook 10 visits to Africa between 2014 and 2020.”

Since 1999, China’s ‘Going Out’ strategy has encouraged Chinese companies to invest beyond China, including in Africa. In November 2003, the first Forum for China-Africa Cooperation summit was held in Beijing.

Russia, for its part, has taken a different path.

“Unlike most major external partners, Russia is not investing significantly in conventional statecraft in Africa — e.g., economic investment, trade and security assistance,” according to a report by Joseph Siegle, director of research for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. “Rather, Russia relies on a series of asymmetric (and often extralegal) measures for influence — mercenaries, arms-for-resource deals, opaque contracts, election interference, and disinformation.”

The competition for Africa among these three competing superpowers, while not devoid of benefits to the continent, has come with costs and led to suspicions and accusations by Africans and the superpowers themselves.

China, for example, is accused of holding down many African countries with loans mainly tied to its infrastructure projects. The U.S. is accused of championing regime change in the continent and seeking to impose Western concepts such as LGBTQ rights on African countries known for their conservative ways.

Generally, however, the influence card is one the three countries wield at various levels of their interventions. Also, questions are asked in some quarters about transparency and accountability, about how some of the financial pledges are fulfilled or deployed.

Olobo Maurice

Just because the U.S. has poured lots of money into Africa doesn’t mean the relationship is healthy, according to Olobo Maurice, a Ugandan consultant on finance and risk management. “If genuinely we want to see change in Africa, the U.S. needs to start looking at Africa (as) a partnership. We should foster partnerships and collaborations in research, education, industry, etc. and focus on key sectors that have multiplier effect to improve livelihood in Africa.”

Speaking of Uganda in particular, U.S. involvement appears to have decreased while Chinese investment has increased, Maurice said. “The Chinese investment and involvement in the economy is huge. I see the U.S. influence has dwindled. But there are still opportunities for the U.S. to get involved in the future of Africa. The U.S. needs to start looking at Africa as a business partner rather than an aid destination.”

Beyond outside help, however, Maurice insists that “the solution for Africa resides with Africans.”

Emmanuel Ogebe, a U.S.-based Nigerian lawyer, also thinks so.

Emmanuel Ogebe

Recent financial donations from the U.S. to Africa are a response to the Chinese incursion into Africa, but they seem to be coming late, Ogebe said. “A source at the U.S. embassy told me there are over 300,000 Chinese currently resident in Nigeria and a Nigerian lawyer, in a public statement, said that those people (Chinese) are expatriating — not repatriating — over a billion dollars’ worth of resources out of Nigeria every year unchecked. So, the U.S. intervention is coming very late.”

He added, “In Central African Republic, the Russian Wagner Group is lifting half a billion dollars out every year from its mining industry. That’s the agreement they have with the Central African Republic government to provide them security. And that’s part of what the Wagner group is using to sustain its war effort in Ukraine. The U.S. intervention is coming at a time it was expected to help pressure Nigeria to stay on the part of democracy. Unfortunately, because the U.S. is now trying to compete with other powers, it is no longer standing for true democracy in Nigeria as we just saw in the recent Nigerian elections.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.