Over the July 4 weekend, hundreds of museum-goers waited in line several hours to get a glimpse of one of the Western world’s foundational political documents. The fragile sheet, written in an elegant hand, tells the story of a people oppressed by an unjust English king and teetering on the brink of war.

Setting their differences aside, and invoking God’s blessing, the nation’s leaders had gathered to compose this document expressing their grievances and making a case for their country’s independence. This declaration would go on to inspire generations of patriots then and now to fight for the freedom — of Scotland.

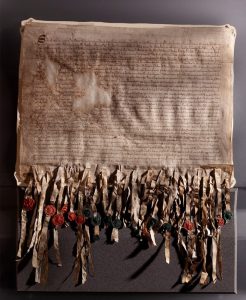

Wax seals affixed to the Declaration of Arbroath confirm that those named in the Declaration’s preamble authorized its message. (Image: Mike Brooks © King’s Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland)

Yes, Scotland has its own declaration of independence, the “Declaration of Arbroath,” which predates the American Declaration of Independence by more than 400 years and, according to some historians, may have inspired it.

Like the U.S. Declaration of Independence, Scotland’s famous declaration has taken on a life of its own as successive generations of Scots have received and wrestled with its meaning. The Declaration of Arbroath raises questions about the context, interpretation and impact of historical documents — be they for the state or the church.

Origin story

Written in 1320 on vellum made of calfskin, the Declaration of Arbroath is rarely displayed in public. It was last exhibited 18 years ago, and the recent viewing at the National Museum of Scotland set strict limitations on lighting and temperature to preserve the 700-year-old artifact.

Alice Blackwell

“It’s very old, it’s very fragile,” said Alice Blackwell, senior curator of Medieval archaeology and history at National Museums of Scotland.

Further, “it wouldn’t have been known as the Declaration of Arbroath when it was written and in the centuries after,” she added. This moniker evolved in tandem with the document’s interpretation, influenced by the Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration of Arbroath originally was a letter addressed to Pope John XXII composed by Scotland’s most powerful barons.

“It’s written in Latin and at the bottom of the text are a number of pieces of parchment to which are attached seals of people named in the document,” Blackwell said. Some of the wax seals depict knights on horseback, others the heraldic shields carried by those knights. Originally 50 in number, the seals dangle from the document like tiny red and green Christmas ornaments. Red for the major barons and green for the minor ones. They add visual support to the barons’ petition on behalf of their king, Robert the Bruce.

Bruce needed all the support he could get. Scotland’s war with England continued, despite several decisive Scottish victories, including the most famous at Bannockburn. Many Scottish nobles still welcomed English rule if it meant stability.

A diplomatic document

One of these, Edward Balliol, son of Scotland’s former king, was proving a formidable rival for the Scottish throne. If Robert the Bruce and Scotland were to survive, they needed Pope John XXII’s blessing.

Dauvit Broun

“The papacy is the equivalent of the UN in this context, and so if you’re wanting to have your independence recognized, it’s got to be by the pope or it’s not really going to count,” said Dauvit Broun, professor of Scottish history at the University of Glasgow.

Like the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration of Arbroath is a diplomatic document whose chief aim is to present a united front to enlist international aid. Only later would both declarations develop internal audiences.

With their wax seals and august titles, the barons behind the Declaration of Arbroath lived at the apex of an Anglo-Norman feudalist society. According to protocol, the declaration lists their names first followed by the “whole community of the realm of Scotland.” A citizenry with a voice, this “community of the realm,” was a very new idea in English political thought. With the advancement of the English common law and creation of Parliament, some political theorists were suggesting knights, burgesses and prominent citizens might have a role to play in governance, especially in matters of taxation.

It would be too great a leap at this point to say the barons thought “all men are created equal.”

It would be too great a leap at this point to say the barons thought “all men are created equal.” This was still a document of the barons, by the barons, for the barons. However, it’s worth remembering that the signers of the Declaration of Independence, many of whom considered themselves the barons of their day, only intended equality for white men of property. Yet both documents sowed the seeds for something greater.

The Declaration of Arbroath narrates the Scottish people’s mythic/historic journey from Scythia to Spain to Scotland and its unbroken line of 113 Scottish kings. According to Broun, “What they’re trying to show is that Scotland is an independent kingdom, always has been.”

Apostolic connections

The document’s arguments emphasize the country’s apostolic connections as well. In what might be described as “Scottish exceptionalism,” the letter reminds Pope John XXII that Jesus Christ himself chose the people of Scotland to receive the gospel from no less than St. Andrew, “the Blessed Peter’s brother.” Since the pope stands in Peter’s place, and Scotland had no archbishop, the nation had received special protection from the pontiff in the past.

“That’s them pulling at the heartstrings and saying you owe us,” Broun said.

Bruce himself is compared to the Apocrypha’s Judas Maccabeus, who led a small band of Jewish revolutionaries against the might of the Seleucid empire and restored Israel’s independence. For his dedication, and with “due consent and assent,” the barons made Robert the Bruce king of Scotland.

Statue of Robert the Bruce at the Site of the Battle of Bannockburn near Stirling.

‘As long as but a hundred of us remain alive’

The Declaration of Arbroath then states that, should any king of Scotland ever submit to England and become “a subverter of his own rights and ours,” he will be driven out of power and replaced because “as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule.”

The writers of the Declaration of Independence embraced a similar idea 450 years later that governments derive their power from the “consent of the governed,” therefore the people had a right to “alter or abolish” those governments when they were unjust.

Such a stance seems natural now; however, this was a view not shared by many in the late Middle Ages. Even the barons of Scotland didn’t believe the peasants plowing their fields had any right to revolt.

“There has been quite a lot of attention given to that particular clause threatening to depose Robert Bruce,” cautioned Broun. “There isn’t any evidence that it was understood at the time as being a great constitutional principle about the sovereignty of the people.”

Most famous line

What follows next is the most well-known passage of the petition, which graces merchandise in souvenir shops across Scotland. “It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honors that we are fighting, but for freedom — for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Tourists might be dismayed to learn that this famous quote originated with the Roman historian Sallust; but those who wrote the Declaration of Arbroath knew what they were doing.

“They’re not just making any statement about freedom. Those listening to it may hear that and associations may trigger in their mind that this is extremely impressive,” Broun said. The quote has been slightly altered from the Latin original to emphasize the altruism of the Scottish people and the centrality of liberty, both individual and communal, in the life of a nation.

The Scottish nobles discussed all these ideas at Newbattle Abbey. Chancery scribes then composed the final letter at the Abbey of Arbroath, where the document gets its name.

“It was a powerful and seemingly effective statement,” said Alice Blackwell. Pope John XXII acknowledged Bruce as the “illustrious king of Scotland.” He urged peace between Scotland and England, which eventually came to pass in 1328, and allowed the bishop of St. Andrews to anoint kings of Scotland on his behalf.

A life of its own

The Vatican’s copy of the declaration is lost to history; but fortunately, Bruce’s scribes kept a “file copy” to hold those who applied their seals to the Declaration of Arbroath accountable. This copy is the one exhibited at the National Museum of Scotland.

By the end of the 14th century, the Declaration of Arbroath began to take on a life of its own. “The main significance is, it became part of the standard account in Latin of Scotland’s history of a kingdom, and the freedom of the kingdom,” Broun said.

In 1689, the Latin text was translated into English and published in response to the removal of James II from the English throne. The letter was divested of its wax seals and reduced in size from 19 inches of parchment to a mere pamphlet. In an early example of Marshal McLuhan’s theory that “the medium is the message,” the Declaration of Arbroath’s mass production allowed for its mass consumption, which implied its message was for the masses.

The Declaration of Arbroath prepared to go on display at the National Museum of Scotland. (Image: Mike Brooks © King’s Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland)

Later, Scottish writer James Boswell read a printed copy of the Declaration of Arbroath and was so moved by the Sallust quote that he added it to the title page of his 1768 narrative of the Corsican revolution. This was the first time the document was associated with an armed overthrow of government, but it wouldn’t be the last. Boswell’s account of Corsica’s struggle for independence was a best seller in Colonial America. The Sons of Liberty toasted Pasquale Paoli, the hero of Boswell’s book, and John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, named a ship after him.

Members of the Continental Congress, seeking support for their separation from England, looked to various historic documents, such as the Magna Carta, to make their case to the world. Could the Declaration of Arbroath, with its talk of liberty and threat to depose an unjust king, have been one of their sources of inspiration?

Blackwell is skeptical: “Though this is a nice idea that the Declaration of Independence took inspiration from the Declaration of Arbroath, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that we can point to for that.”

One of Thomas Jefferson’s mentors at William and Mary, Professor William Small, grew up near Arbroath; however, no copy of the Declaration of Arbroath has been found in Jefferson’s library.

Historians looking in the library of fellow Declaration Committee member Benjamin Franklin might come to a different conclusion. In 1775, while collecting sources on international law for the Continental Congress, Franklin obtained copies of Swiss lawyer Emer de Vattel’s book, The Law of Nations, which included a lengthy footnote quoting the Declaration of Arbroath.

Nevertheless, a link has been made. Since 1998, America celebrates Tartan Day on April 6 in honor of the possible connection between the two declarations and the contribution of Scottish immigrants to the United States.

Back in circulation

Regard for the Declaration of Independence developed along a similar trajectory. Once America won its freedom from England’s king, the document that first declared it fell out of circulation for a time until it was resurrected in the 19th century as an argument for the rights of marginalized people.

The Seneca Falls convention for women’s rights amended the Declaration of Independence to read “all men and women are created equal.” Frederick Douglas in his What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? called the principles of the Declaration of Independence “saving principles.” And Abraham Lincoln believed it provided the light by which Americans should read the United States Constitution. Later luminaries like Martin Luther King Jr. and Harvey Milk also cited the Declaration of Independence in their quests for equality.

The Declaration of Arbroath similarly became a rallying for the country’s working class. Circulating libraries in lowland Scotland provided laborers access to books of Scottish history that included the Declaration of Arbroath, which helped inspire the strikes of the early 1800s. In 1820, a rally of 1,500 weavers and miners gathered on the anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn at the site of the battle to invoke the struggle of Medieval Scots against tyranny.

In 1920, Scotland celebrated the Declaration’s 600th anniversary with a gathering of dignitaries at the Abbey of Arbroath. The event was dominated by voices in favor of empire, until the moderator of the United Free Church of Scotland delivered his dissenting address. In his view, the Declaration of Arbroath served as an example to nations around the world striving for self-government. The right of a people to determine their own destiny is a basic human right, he said. Not only is it impossible to govern a people against their will, but it is wrong. When Germany attempted to do that very thing in World War II, the UK distributed copies of the Declaration of Arbroath to schoolchildren to bolster morale.

After the war, the Declaration of Arbroath was once again in the news when four students from the University of Glasgow stole the Stone of Scone from beneath the coronation chair in Westminster Abbey and later deposited it in the Abbey of Arbroath draped in the Scottish flag. The stunt in support of Scottish home rule renewed the relationship between the declaration and the independence movement in Scotland, which has only grown in the decades that have followed.

“In Scotland, it has a very special place as a statement of Scottish freedom,” Broun said. “It has this powerful presence in Scottish identity today.”

Analysis

Both the Declaration of Arbroath and the Declaration of Independence are documents of their times that have evolved to become documents for all time. They are what Blackwell calls “living documents” whose meanings and relevance change as nations and individuals continue to engage with them.

Although both declarations began as diplomatic correspondence by their country’s elite to further a particular political agenda, the Declaration of Arbroath and the Declaration of Independence are now considered foundational pillars in the national identities of Scotland and the United States.

But now that the Declaration of Arbroath is back in the archives, and the smoke from the Fourth of July fireworks has settled, how do we live with living documents and why are they so necessary, especially for the people of Jesus?

“We must continually engage the foundational documents of our nation not just from the perspective of the privileged, but from the point of view of those who are marginalized.”

We must continually engage the foundational documents of our nation not just from the perspective of the privileged, but from the point of view of those who are marginalized. Both the Declaration of Arbroath and the Declaration of Independence were composed by those in positions of power. However, it was the marginalized, the poor, the enslaved, the disenfranchised who have breathed new life and meaning into them and kept these documents alive.

This is why originalism is problematic. Limiting interpretation of a foundational document solely to what it meant at the time of its composition ignores the lived experiences of people and societal advancements, both philosophical and technological, that followed. Originalism itself developed in the United States as a reaction to the radical societal change of the 1960s and ’70s, when conservatives tried to curb the expansion of rights for women and minorities — the very antithesis of equality.

Thomas Jefferson himself said, “The earth belongs to the living and not to the dead,” therefore the nation’s constitution and laws should be a revised every 20 years to reflect changes in the country.

The church also belongs to the living. The great cloud of witnesses in Hebrews 12 is not there to ensure things remain unchanged, but to inspire believers to “run with perseverance the race set before us,” not behind us.

If the foundational documents of our churches are living documents, then they also must adapt to a changing church and a changing world. Do our constitutions and bylaws, largely crafted by white men in Sunday suits, meet the needs of members who work multiple low-wage jobs or single mothers stretched in multiple directions?

More importantly, are our statements of vision and identity mere platitudes with a public relations agenda or are we living in to and up to them? If we post “All are welcome” on the church sign, do we really mean all? If we claim to “to love God, love church, love neighbor” but business meetings are more about Robert’s Rules of Order than the Golden Rule, is the love of God really in us? Are we anything more than a clubhouse with a steeple? Do we have something worth declaring?

Quite often, the dissonance between word and deed within our congregations is the same as it is beyond the church doors when we proclaim “all are created equal” but continue to discriminate.

The Declaration of Arbroath and the Declaration of Independence endure because they evolved into something greater. Churches could choose to do the same, and they are at an advantage, because they have the Holy Spirit to guide and enable this transformation.

Unfortunately, most choose to ally themselves with the barons of this world and bolster the budget rather than stand with the marginalized and break down barriers.

“It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honors that we are fighting, but for freedom,” says the Declaration of Arbroath. The Apostle Paul tells us that it is for freedom Christ has set us free, so that we might express our faith in love. Ultimately love is the only thing that matters.

Let us not wait until there are only a hundred of us left to make it so.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.

Related article:

What’s a Baptist to think of the coronation of Charles III?