Black and white Americans disagree greatly on how to handle Confederate memorials, despite largely agreeing on the need to acknowledge slavery and the discrimination and violence against racial minorities, a new study shows.

The August report by Public Religion Research Institute and E Pluribus Unum combined national polling with 26 focus groups in 13 Southern states to explore American attitudes on Confederate statues and other displays and the role religion plays in shaping those perspectives.

White and Black focus groups were divided when asked what, if anything, should be done with monuments and other memorials that remain on display in parks, downtown spaces and other public venues.

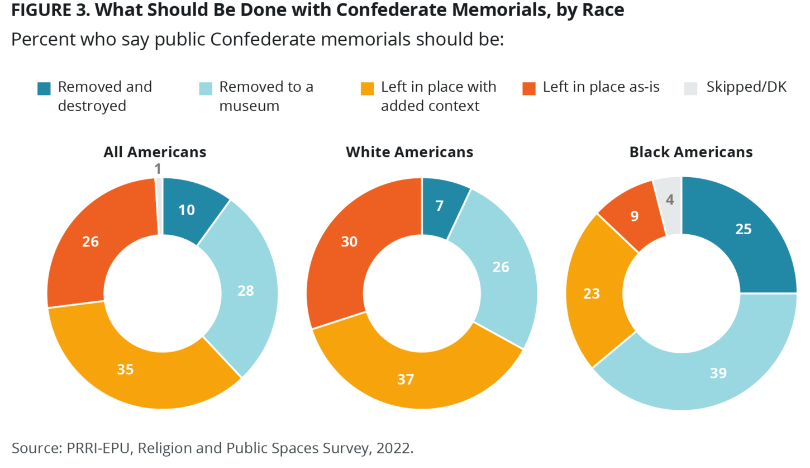

“Three in 10 white Americans (30%) say the statues should stay in place as they are, 37% say they should be left in place but have additional context added, 26% support moving the statues to a museum, and 7% say the statues should be removed and destroyed. Black Americans fall almost completely in the opposite direction: 9% say to leave the statues as they are, 23% say to leave them and add context, 39% support moving them to a museum, and 25% would like to see the statues removed and destroyed. Overall, 26% of Americans support leaving the statues as they are, 35% say leave them but add context, 28% say put them in a museum, and 10% say they should be removed and destroyed.”

The study also uncovered significant support among Black and white Americans for telling the truth about the history of slavery and the subsequent oppression of racial minorities, including 90% of white respondents and 89% of Black Americans.

“Substantial majorities also support ‘efforts to promote racial healing by creating more inclusive public spaces in their communities,’ including 77% of white Americans and 87% of Black Americans.”

Most also agreed it is appropriate to use public spaces to memorialize individuals who have had a positive impact on a community.

“It would be cool if someone from that area had done something to name something in their whole area about them. I would feel more like excited [if] it was somebody from the area or somebody who did something specifically for our area was memorialized in some kind of way,” a Black Alabama man said during a focus group meeting.

Unity on that issue was documented by the national survey, which asked respondents to select three of 12 values they consider most important in erecting art or new monuments in public spaces.

“The top three values selected were service and contributions to the community (47%, including 50% of white Americans and 43% of Black Americans), the idea of a nation of immigrants (42%, including 42% of white Americans and 29% of Black Americans), and patriotism (39%, including 46% of white Americans, but just 14% of Black Americans).”

Many respondents concurred that taking action against existing Confederate monuments is either unnecessary or a waste of resources, the report found. “Some white participants felt the process would lead to a constant cycle of building and tearing down monuments once the members of a future generation decide they are offended by them. Several Black participants felt that taking down monuments or adding context to them would be empty gestures that did little to improve the economic situation or daily lives of Black residents.”

Despite the accord on numerous issues, the path toward resolution will be complicated by divergent views on the importance of racial identity and faith in deciding the fate of monuments, researchers said.

“Black participants were very open about their own experiences with racism and how the memorials hurt them.”

“It was clear in the focus groups that the white and Black participants had vastly different levels of awareness and comfort when discussing their racial identity. Black participants would frequently jump right to discussions of Confederate memorials when talking about public spaces, even before the moderator broached the topic, while white participants had to be directed to consider the memorials. Black participants were very open about their own experiences with racism and how the memorials hurt them.”

The survey confirmed those sentiments, with 43% of Black Americans reporting experiences of hostility and discrimination based on skin color, compared to 10% of white Americans. Among all American, 20% reported having such experiences.

“While most white focus group participants were defensive about the memorials and generally wanted to leave them alone, a few did recognize that the memorials might be problematic for Black people,” the report says. “Particularly in Richmond, where memorials had been removed, white participants recognized the hurtful nature of the monuments.”

Focus group meetings revealed that opinions about the handling of Confederate statues were informed by divergent views of history held by Black and white members.

“The national survey bears this out as well: When Americans were asked if monuments to Confederate soldiers were more a symbol of Southern pride or more a symbol of racism, about two-thirds (64%) said they were symbols of Southern pride, but only 30% of Black Americans agreed, compared with 73% of white Americans. By contrast, most Black Americans (63%) say that such monuments are symbols of racism, while only 25% of white Americans say the same.”

Black participants were more likely to identify the key role of religion in bringing about potential reconciliation and often noted how unhelpful white churches have been in the effort.

“Some Black participants also shared that they believe racial segregation within Southern religious communities contributes to the difficulty of addressing racism in the wider community, because it contributes to white Christians’ unwillingness to consider the perspectives and experiences of Black Americans,” the report explains.

Black participants often emphasized the important role their congregations have in preserving Black history and in the movement to remove Confederate symbols from public spaces. “Other Black respondents said that while church leaders remain essential in driving these conversations, ultimately the work involved in racial healing relies on community members themselves.”

White participants were much less likely to see the relevance of religion in the debate about memorials.

White participants, on the other hand, were much less likely to see the relevance of religion in the debate about memorials, the report said. “They also tended not to mention religion playing a role in shaping attitudes about racism and inclusive public spaces.”

Moving forward will not be easy despite the survey findings that 87% of Americans want to build relationships with members of other races and 93% say they respect those with whom they disagree. A common attitude among the focus groups was a “cynicism toward others,” the report says. “Neither the Black nor the white groups seemed to trust the other. This again speaks to the idea that despite people having shared visions for the future across racial lines, the plans could fall apart during any actual implementation.”

Related articles:

On question of what to do with Confederate monuments, Americans are all over the map

Of statues and stories: Reckoning with the Lost Cause | Opinion by Greg Garrett

As the Confederate monuments come tumbling down, half of Americans still favor their presence