A “prominent” marker on the campus of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary acknowledging the sins of the institution’s slaveholding founders is smaller than a nearby banner bearing the image of current seminary President Al Mohler, the Louisville Courier-Journal reports.

The 20-by-30-inch bronze marker in the lobby of Broadus Chapel came about when Mohler and seminary trustees declined requests to remove the names of slaveholding founders from campus buildings three years ago.

“Sorry you did not see the memorial. It is quite prominent.”

One of the loudest critics calling for taking names off buildings at the Louisville, Ky., school was Dwight McKissic, pastor of Cornerstone Baptist Church in Arlington, Texas. Until this summer, McKissic maintained a high profile in the SBC, but he and his congregation recently announced they are leaving the denomination because of restrictions placed on women in ministry. Mohler also is a key figure in advocating for those restrictions.

In 2020, when seminary trustees voted not to change the names of buildings, Mohler promised McKissic he would erect a memorial to those people previously enslaved by Southern and its founders.

But when McKissic recently visited the campus, he couldn’t find the memorial. He tweeted his disappointment.

Mohler tweeted back: “Sorry you did not see the memorial. It is quite prominent. You had suggested it, and we followed up as promised. Your suggestion was right and timely. If you have time to come back, I will gladly show it to you this afternoon.”

McKissic couldn’t go back, but another Black pastor went in his place. What he was shown is a small plaque affixed to a secondary chapel.

Broadus Chapel is a new 200-seat chapel inside an academic building. The chapel is used for weddings and preaching labs. It is not the primary chapel on campus. And it is named for one of the four slaveholding founders, John Broadus.

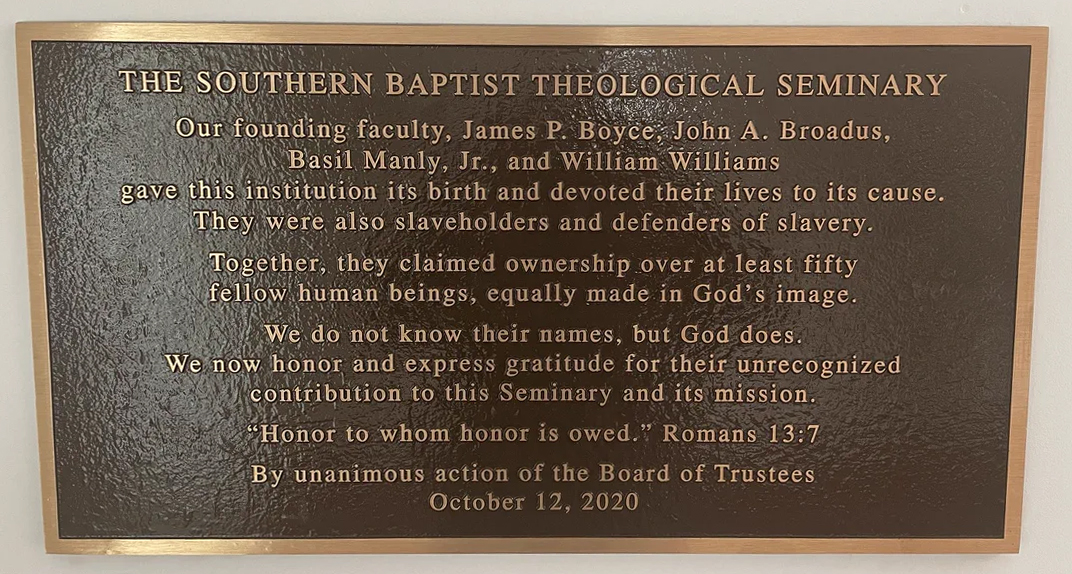

The plaque states: “Our founding faculty, James P. Boyce, John A. Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams, gave this institution its birth and devoted their lives to its cause. They were also slaveholders and defenders of slavery. Together, they claimed ownership over at least fifty fellow human beings, equally made in God’s image. We do not know their names, but God does. We now honor and express gratitude for their unrecognized contribution to this seminary and its mission.”

Discovery of this “prominent” memorial caught the attention of Brian Kaylor, editor of Word&Way newspaper, and also the attention of a religion writer for the Courier-Journal.

Kaylor noted he could find no evidence of any announcement by the seminary of the marker, no dedication, no prayer, no anything. But in the seminary’s printed report to the SBC annual meeting this June, published in a book called the Book of Reports, Mohler said the seminary had “recognized the moral reckoning to which we are called by establishing a major marker on the campus which acknowledges the sin of American slavery and the contributions made to this institution by countless slaves.”

McKissic and other Black pastors don’t see this obscure plaque as either “major” or “prominent.”

Kaylor said seminary officials did not respond to his request for comment on the marker. Likewise, the Courier-Journal said neither Mohler nor his media handler responded to its questions.

Since ascending to the presidency 30 years ago, Mohler has celebrated the seminary’s founders because he shares their Reformed theology — a kind of Baptist Calvinism that had gone out of vogue in the 20th century but that now has roared back, largely under Mohler’s influence.

He has portrayed himself as returning the 164-year-old school to its founding vision, after it was carried astray by liberalism.

Yet that founding vision inescapably includes white supremacy and slave ownership. To dishonor the memory of the men whose theology he adores puts Mohler in a pickle when confronted with the facts on race.

“If the founders were abortion advocates, they would have no hesitancy in removing their names.”

Thus, even the plaque honoring the unnamed slaves begins by honoring the four slaveholders who “gave this institution its birth and devoted their lives to its cause.”

Not only should the memorial be so prominent on campus that anyone could find it without help, but the best answer still is to take the slaveholders’ names off the buildings, McKissic told the Courier-Journal.

“If the founders were abortion advocates, they would have no hesitancy in removing their names,” the pastor said.

In 2020 — amid the nationwide racial reckoning prompted by George Floyd’s murder by police officers in Minneapolis — Mohler told trustees just as the Bible retains the names of imperfect, sinful leaders like Abraham, Moses and King David, so the seminary will do with the names of James P. Boyce, its first president, and founding faculty members John Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams.

“We stand in conviction on the great truths of the Christian faith and in confessional agreement with our founders,” he said. “Their theological orthodoxy and Baptist confessionalism are an invaluable inheritance, and we stand with them in theological conviction, period. But we deal honestly with their sin and complicity in slavery and racism.”

Related articles:

Southern Seminary won’t rename buildings but creates scholarships for Black students

Baptist Calvinists defend slavery of Southern Seminary founders | Analysis by Brian Kaylor

Panel urges Southern Seminary to make amends for past racial sins