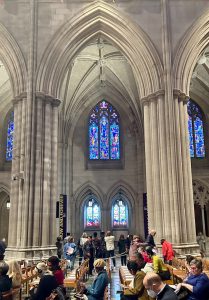

On Sept. 10, 2017, I sat in Washington National Cathedral as Dean Randolph Hollerith announced that after almost two years of discussion, prayer and discernment, the Cathedral Chapter had decided to remove a set of stained-glass windows donated by the Daughters of the Confederacy.

This was pre-George Floyd, pre-pandemic, pre the controversy about Confederate memorials and monuments, so very early in any reckoning with race and symbols of racism. Those windows, representing Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee as stainless Christian saints, had been donated to the Cathedral in the 1950s during the struggle for Civil Rights, and they had remained (appropriately) on the south side of the nave for year on year.

Greg Garrett

In his sermon, Dean Hollerith spoke of the conversations that had led to that outcome, and the theological basis for it:

I can tell you this was not an easy decision, a quick decision or one that anyone took lightly. Rather, after almost two years of conversation and programming around these windows and the larger issues of race, racism and the legacy of slavery, the bishop and I, along with the Chapter, came to the decision that these windows were an obstacle to our mission to be a house of prayer for all people; they were an obstacle to the work of building the Beloved Community, and we needed to let them go.

There was a time in my life I would not have minded those windows. Might even have celebrated them. I have been in two fistfights in my increasingly long life. One of them was over being called a “damn Yankee” by my third-grade best friend on a North Carolina playground. It was one of the worst insults one white Southern boy could offer another.

I was steeped in the myth of the Lost Cause, raised to think of Confederate heroes as paragons of virtue. Like Brig. Gen. Ty Seidule, who wrote the wondrous Robert E. Lee and Me, my culture taught me to think of Robert E. Lee as a saint worthy of emulation.

But, like Gen. Seidule, as the years go by, as I have leaned increasingly into the work of racial healing, it has become more and more clear that those myths like the Lost Cause that served to seal my own place atop American hierarchies have excluded so many more and, so, along with Dean Hollerith on that Sunday morning in 2017, I was understanding how so many people who visited America’s House of Prayer for All People might feel excluded by stained glass windows extolling the sainthood of slaveholders and traitors to the cause of American democracy.

The National Cathedral — like America — has not always been a welcoming place for people of color. In addition to those windows donated by the Daughters of the Confederacy to continue preaching the Lost Cause, the Cathedral is the burial site of confirmed racist Woodrow Wilson, who showed The Birth of a Nation in the White House, whose racist A History of the American People is actually cited in that most racist of films, and who sought to segregate — or re-segregate — the government he inherited, the nation he led.

The National Cathedral — like America — has not always been a welcoming place for people of color. In addition to those windows donated by the Daughters of the Confederacy to continue preaching the Lost Cause, the Cathedral is the burial site of confirmed racist Woodrow Wilson, who showed The Birth of a Nation in the White House, whose racist A History of the American People is actually cited in that most racist of films, and who sought to segregate — or re-segregate — the government he inherited, the nation he led.

It doesn’t seem like a great testimony to tolerance that Wilson, the only president buried in Washington, D.C., should be interred in the Cathedral. My friend Kelly Brown Douglas, who is now the Cathedral’s distinguished canon theologian, once thought of the Cathedral as “a ‘polite’ but unwelcoming place for Black people,” and she “vowed never to walk into the Cathedral again, much less worship there.”

I am a witness to these understandings about the Nation’s Church. After Kelly, Atlantic Monthly editor Vann Newkirk II and I had engaged in an onstage conversation about Hollywood films on race for our first Long Long Way Film Festival one night in 2018, I walked down the hill to the Washington Metro behind a group of Black students and faculty from Howard University who simply could not believe the National Cathedral was sponsoring a program on race and justice, that they even cared about such things.

Black people never had thought of the Cathedral as a safe place, and I can certainly understand why.

But things can change. On Saturday, Sept. 23, the Cathedral dedicated new stained-glass windows by the renowned African American artist Kerry James Marshall to occupy and sanctify the space where the Confederate saints Lee and Jackson so long had stood. At the service, Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. read from the letter to the Romans. Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson read from Dr. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” One thousand people lifted up their voices to sing “The Black National Anthem” “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

“It would be easy to say that over the last eight years, we at the Cathedral changed some windows. But in reality, the windows changed us.”

Then the next day, on Sunday, Sept. 24, on the 115th anniversary of the founding of the Cathedral, the Episcopal bishop of Washington, D.C., Mariann Budde, preached on the necessity of recognizing the complicity of the church in not recognizing how divisive such a set of symbols could be, on her own complicity in walking by them time after time without reflecting that Black visitors and parishioners would feel excluded and pained by their presence. From the majestic Canterbury Pulpit, Bishop Budde confessed the negligence of the Cathedral and the church as well as her own failure, and she apologized for the pain and unthinking acceptance that had allowed such a painful witness in such sacred space.

The weekend was a signal moment of truth telling, repair and correction, one I badly needed to witness in a world where it sometimes seems there is no possibility for reconciliation. I see the divides in American culture that are shaped by race, religion, politics, culture wars, and it certainly prompts despair, not hope. In fact, I was asked on BBC Ulster if James Baldwin’s message of love and inclusion still has any chance of being heard in America. And what I told Sunday morning host Audrey Carville was that Baldwin’s conclusion at the end of his life was simply this: We can do and be better than we are.

The weekend was a signal moment of truth telling, repair and correction, one I badly needed to witness in a world where it sometimes seems there is no possibility for reconciliation. I see the divides in American culture that are shaped by race, religion, politics, culture wars, and it certainly prompts despair, not hope. In fact, I was asked on BBC Ulster if James Baldwin’s message of love and inclusion still has any chance of being heard in America. And what I told Sunday morning host Audrey Carville was that Baldwin’s conclusion at the end of his life was simply this: We can do and be better than we are.

And, I told her, I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning if I didn’t believe that.

Dean Hollerith says: “It would be easy to say that over the last eight years, we at the Cathedral changed some windows. But in reality, the windows changed us.”

By walking alongside each other in the process, by telling painful truths and leaning into scary conflict, Washington National Cathedral and its leadership offer us all a lesson.

It is never too late to confront the wrongs of long ago.

It is never too late to admit and address our history.

And we can do and be better.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Seminary removes stained glass windows celebrating conservative takeover of SBC

A surprising window into Black Jesus | Analysis by Kristen Thomason