When Phyllis Webstad was 6, her grandmother took her to town to buy a new outfit for the first day of school.

“I chose a shiny new orange shirt. It was bright and exciting, just how I felt about going to school for the first time,” she recalled. However, when Webstad, who is Northern Secwepemc (Shuswap) from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation (Canoe Creek Indian Band), arrived at St. Joseph Mission Indian Residential School in Williams Lake, British Columbia, the nuns who ran the school confiscated her new shirt and callously ignored her distress and confusion.

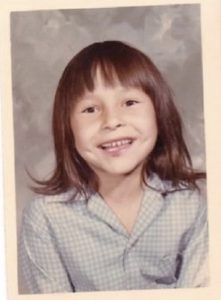

Phyllis Webstad age 6.

“No matter how much I cried, no one would listen,” she said.

The purpose of boarding schools, like the one Webstad attended, was to assimilate indigenous children into the dominant settler cultures of the United States and Canada by forcibly removing them from their families and communities.

For this reason, Benjamin Jacuk (Dena’ina Athabascan, Sugpiaq), indigenous researcher at the Alaska Native Heritage Center, prefers a different name for these schools. “I use ‘assimilative institutions’,” he said. “I try to add in ‘assimilative’ because ‘indigenous boarding schools’ makes it sound like we did this to ourselves. (These) places deemed native culture as something subhuman. The idea was to completely wash it away.”

When children arrived at the schools, just like with Phyllis Webstad, their clothing was taken, their hair was cut, and they were severely punished for speaking their native languages.

“Languages are that gateway to understanding a culture, and the way you understand God,” Jacuk said. “When you sever that place, that true way of understanding God the Creator, I see nothing closer to the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit than that. Not only are you trying to take away the humanity of entire populations, you’re also trying to sever their connection with God.”

Even today, many tribal elders are still afraid to speak their native language in public. Many others never learned their tribal language at all.

Religious roots

These assimilative schools targeted Native American, Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian children. Although funded by the government, more than half were run by various religious denominations.

After insistent petitioning by the Kentucky Bracken Association of Baptists and others, Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act of 1819. The federal government provided seed money to missionaries and churches to set up schools in “Indian territory.” The schools would then “civilize” indigenous children by forcing them to abandon their native traditions and convert to Christianity.

“In order to really be a Christian, in order to really be converted, you also have to be Americanized.”

As Jacuk points out, “The belief was: In order to really be a Christian, in order to really be converted, you also have to be Americanized.”

Ironically, according to Jacuk, a “significant portion” of Alaskan Natives already were active members of the Russian Orthodox church. Russia claimed Alaska as part of its territory until 1867 when they sold Alaska to the United States. The Orthodox monks allowed Alaskan Natives to keep their language and culture because they believed the indigenous people “have always known God.”

When the Protestant missionaries arrived, “We (already) knew a liturgy. We knew Christian tradition far better than a lot of the Methodists that came over, or American Baptists. Yet even with all of that, it was never enough, (because) at the end of the day, it wasn’t about conversion.”

Money to be made

The real reason churches eagerly sought the opportunity to create assimilative schools for the government in places like Alaska, Hawaii and elsewhere in the U.S. and Canada, was the money.

Richard Johnson

Those in charge regularly embezzled the money assimilative schools received from the federal government. Richard Johnson, a politician who established the Choctaw Indian Academy on his plantation in Scott County, Ky., wrote to his close friend, Baptist minister Thomas Henderson, superintendent of the academy: “Let everything you do be upon a frugal scale. Save me all you can — I am hard pressed.”

Johnson later was elected vice president of the United States and used his influence with the War Department to obstruct complaints from students and tribal leaders. A cholera outbreak raged for three weeks at the school and eventually killed 24 people before Johnson and Henderson, pressured by government officials, heeded demands from Apalachicola Chief John Blunt to return his son and other children to the tribe.

In addition to money, the U.S. government gave churches and denominations tracts of land from Native American reservations and input into presidential appointments. In 1880, representatives from the major Protestant denominations met and devised the Comity Plan. This strategy divided Alaska into different regions in order to determine where each denomination would set up its assimilative schools.

“The first thing that they could agree upon, in their entire histories, was the assimilation of our people.”

Jacuk said this was “Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Episcopal, all coming together in a room in Alaska and circling the pieces they wanted. And so, what you have, at least among Protestants, is the first real ecumenical movement. The first thing that they could agree upon, in their entire histories, was the assimilation of our people.”

These denominations were not coordinating their efforts in order to bring educational opportunities to Alaskan Natives. In fact, recently discovered documents from the Comity Plan prove education never was on the agenda.

Benjamin Jacuk

“It was 100% motivated by how much money they could make,” Jacuk said. “Assimilation turns into a way (of) extracting money in different ways, shapes and forms. If you get rid of the people, you get rid of the problem.” Denominational leaders hoped to increase their personal wealth by extracting natural resources, opening native lands to tourism, and exploiting indigenous labor.

“With the Baptists in particular, the region that they took over is my region, South Central Alaska,” Jacuk said. “My great-grandfather was forced to hunt sea otter in post-Civil War slavery.”

A history of abuse

Untold numbers of students died from malnutrition and inadequate medical care at assimilative schools. A 2007 report by the Boarding School Healing Project revealed schools in South Dakota fed children a single sandwich for the entire day. Other boarding school students died from physical abuse at the hands of clergy and administrators, or even other children who were made to beat their classmates to death. Teachers would force those same children to build the dead child’s coffin.

A convicted sex offender, who cited his arrest on his job application, was nonetheless hired to teach at a Navajo boarding school.

Sexual abuse also was rampant in these schools. According to a report complied for the United Nations, in 1987 the FBI discovered an administrator at a Hopi school in Arizona had sexually abused more than 142 children. Elsewhere, a convicted sex offender, who cited his arrest on his job application, was nonetheless hired to teach at a Navajo boarding school. He later was convicted for abusing the children there as well.

“It doesn’t take a scholar to interpret what Jesus would even think about that,” Jacuk said. “Christ was very clear. Jesus says, ‘If you harm one of these children, it’s better just to kill yourself.’ He doesn’t leave any room to question.”

Children from tribes listed as the most “uncivilized” by religious groups received the worst treatment from those running the schools. “I think they’ve convinced themselves that these are not children yet. We see a lot of before and after pictures. There’s a picture of someone, a kid in (traditional) regalia that’s just labeled ‘savage boy.’ Then, in the next photo, with a clean haircut and dressed in Western clothes, you see him being labeled with his own name, as opposed to ‘savage Eskimo boy,’” Jacuk explained.

Not such ancient history

Looking at such sepia-tone photos could lead one to believe Native American boarding schools and their effects are in the past. However, as Jacuk points out, “It’s something that’s more recent than the Holocaust, and yet we don’t think about the Holocaust as something that was that long ago.” The U.S. government was still opening boarding schools in 1969, and religious groups continued the practice for even longer. Not until 1975 were Native Americans, Native Alaskans and Hawaiian Natives guaranteed the right to self-determination in matters of education under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act.

“I’m a third-generation Indian residential school survivor. My grandmother attended from 1925 to 1935. All of Granny’s 10 children including my mother attended for 10 years from 1954 to 1964. I attended residential school in 1973-1974. My son also attended the last operating residential school in Canada when it closed in Saskatchewan in 1996,” said Phyllis Webstad. Survivors like Webstad suffer from PTSD, anxiety, depression and lingering health problems from their time in assimilative schools. Having grown up away from their own parents, many school survivors struggled when they became parents themselves.

Amy Bombay (Ojibway) at Dalhousie University in Halifax found teens who had a survivor parent were more likely to have suicidal thoughts or attempt suicide themselves. When the assimilative schools disrupted traditional tribal ceremonies and customs, individuals and communities also lost resources to heal intergenerational trauma.

“This history still walks with us.”

“This history still walks with us,” Jacuk said. “We are so much more than that, but it still is here. There is that response (to) being told that indigenous peoples are not human. After you hear that your entire life as a native person, and you don’t have a culture to back up who you are and tell you, ‘You are worth it,’ then a lot of the time suicide becomes the answer.”

Truth and Reconciliation

In an effort to heal the harm done to First Nations, Metis and Inuit communities in Canada, the government launched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as part of the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. The TRC hosted national events across the country to educate members of the public about the residential school era and provide survivors an outlet to share their experiences.

Phyllis Webstad

“I told my orange shirt story for the first time in 2013 when preparation for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission came to Williams Lake,” Webstad said. “Those involved with the event decided to honor the orange shirt as a symbol of the effects of residential schools.”

Phyllis Webstad’s story resonated with other survivors, and in 2015 she, with the help of other First Nation’s members, created the Orange Shirt Society, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness about the impact of residential schools on individuals, families and communities. The society chose Sept. 30 as Orange Shirt Day to commemorate the time of the year when children were taken from their families and forced to attend assimilative schools. “When I heard an elder say September was ‘crying month,’ I knew we had selected the right date,” Webstad said.

Across Canada, school children wear orange shirts in honor of Orange Shirt Day and spend time in class learning about the history of residential schools through books by indigenous authors and media presentations like the animated film The Secret Path. First Nations communities hold powwows, prayer events and healing walks. In some cities, residents erect memorials made of children’s shoes to symbolize the indigenous children who never returned home from assimilative institutions. Canadian Baptist Ministries has created an audio guide for individuals and small groups to use while prayer walking, along with a selection of helpful links to information about residential schools and ways to support the indigenous community.

In 2021, the Canadian government created a federal statutory holiday, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, to honor and coincide with Orange Shirt Day. “It is a day to honor residential school survivors and their families, to remember those who didn’t make it, to highlight progress in the reconciliation,” Webstad explained.

Over the last few years, indigenous and non-indigenous groups in the United States have started observing Orange Shirt Day as well. The Alaska Children’s Trust, with help from the Alaska Native Heritage Center, created a resource for families that explains the history behind Orange Shirt Day. The printable PDF includes discussion prompts, coloring pages and questions for an episode of the PBS cartoon Molly in Denali.

For a long time after leaving St. Joseph Mission Indian Residential School, Phyllis Webstad couldn’t bring herself to wear orange. “The memories of that orange shirt being taken away, and the lack of caring by those who controlled us, would trigger memories of my experiences,” she said. Now through her work with the Orange Shirt Society, she feels differently. “When you wear an orange shirt, it’s like a little bit of justice for us survivors in our lifetime, and recognition of a system we can never allow again.”

Related article:

It’s past time to unearth and acknowledge our role in Native American boarding schools | Analysis by Laura Ellis