The mild 2023 version of Beatlemania hardly compares to the wild 1964 version, but it has brought new musical products.

“Now and Then,” the “last” song from the band, was released Nov. 2 to promote the Nov. 10 release of expanded versions of two collections, “The Beatles 1962-1966” and “The Beatles 1967-1970.”

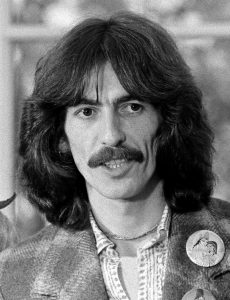

Fewer people noticed the Oct. 24 release of George Harrison: The Reluctant Beatle, Philip Norman’s new 510-page deep-dive bio of the so-called “quiet” Beatle.

Norman, the author of four previous Beatles books, including biographies of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, helps readers understand Harrison’s musicianship, songwriting, Hindu spirituality and essential role in forming the Beatles from the ashes of the Quarrymen.

Norman, the author of four previous Beatles books, including biographies of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, helps readers understand Harrison’s musicianship, songwriting, Hindu spirituality and essential role in forming the Beatles from the ashes of the Quarrymen.

Norman paints a portrait of an “endlessly self-contradictory” artist who: “railed against ‘the material world,’ yet wrote the first pop song complaining about income tax; who spent years lovingly restoring Friar Park, his 30-room Gothic mansion, yet mortgaged it in a heartbeat to finance his friends the Monty Python team’s Life of Brian film; who, paradoxically, became more uptight and moody after he learned to meditate; who could touch both the height of nobility with his Concert for Bangladesh and the depths of disloyalty in his casual seduction of Ringo’s wife.”

Music and drugs inspire spiritual journey

Like many young people during the 1960s, Harrison had a fascination with Eastern spirituality that was informed by music and drugs, including marijuana (introduced to the band by Bob Dylan) and psychedelics.

Eastern music and LSD trips excited a deep spiritual hunger in Harrison that couldn’t be filled by Western pop music or the Sunday school lessons he heard at Liverpool’s St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church.

One unusual side effect of LSD was that Harrison said he heard the phrase, “Yogis of the Himalayas” repeated in his mind, “like someone was whispering to me.”

Harrison would give up psychedelics after a visit to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury late in 1967’s Summer of Love. Expecting to see “a brilliant place with groovy gipsy people making works of art and paintings and carvings in little workshops,” he was shocked by all the strung-out young people.

Once Harrison met Indian musician Ravi Shankar, his spiritual fate was sealed. Sitar studies became doorways into the rich and ancient traditions of Hinduism. Visits to India for music lessons included meditation and teaching sessions with “real-life yogis of the Himalayas.”

“In comparison, the multiplicity of gods invoked by sitar music seemed easygoing, even comforting.”

“George’s last experience of God had been the stringent single deity of his early Catholic upbringing,” writes Norman. “In comparison, the multiplicity of gods invoked by sitar music seemed easygoing, even comforting.”

Competing with John or Paul

Harrison suffered feelings of inferiority long before he began competing against Lennon and McCartney to get some of his own compositions onto Beatles albums.

In songs like Sgt. Pepper’s “Within You Without You,” Harrison combined popular musical styles with themes from ancient Eastern spirituality, a hallmark of his body of work found on his solo albums, from 1970’s masterful All Things Must Pass through Brainwashed, released a year after his death from cancer in 2001.

In songs like Sgt. Pepper’s “Within You Without You,” Harrison combined popular musical styles with themes from ancient Eastern spirituality, a hallmark of his body of work found on his solo albums, from 1970’s masterful All Things Must Pass through Brainwashed, released a year after his death from cancer in 2001.

One of the best ways to appreciate Harrison’s songwriting is by viewing the two-hour Concert for George film, shot at 2003’s all-star memorial concert that featured McCartney, Ringo Starr, and bandleader Eric Clapton, who married Harrison’s ex-wife Pattie, a saga covered in detail in Reluctant Beatle.

Martin Scorsese’s 2011 documentary, Living in the Material World, does a good job of illustrating Harrison’s life story, but Norman’s bio goes deeper and is more detailed.

The Beatles’ visit to India to see Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of Transcendental Meditation fame was front-page news worldwide, but the holy man’s antics soured all but George on any Eastern gurus.

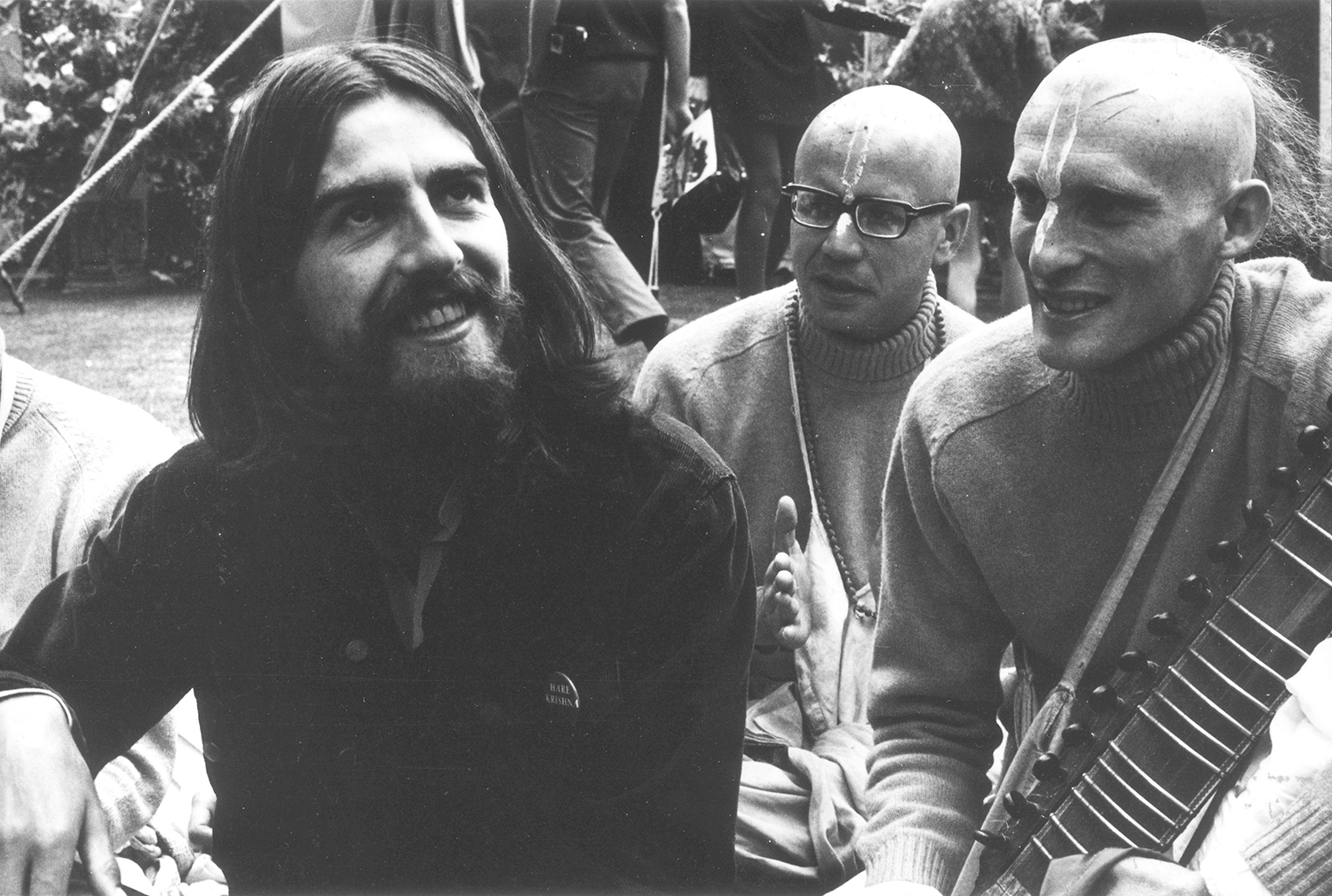

Harrison would find a deeper spiritual brotherhood with disciples of Krishna Consciousness and would financially support the movement’s efforts for the rest of his life (and beyond, with royalties from some songs).

Beatles guitarist and singer George Harrison sits with shaven headed members of a Hindu sect, August 29, 1969. (Photo by Getty Images)

Man of contradictions

The beatific spiritual visions Harrison created through his music didn’t mean he was a saintly or even kindly man, according to those who knew him best, including ex-wife Pattie, who says that early on, George was “sweet and kind.”

But things changed drastically after the band’s pilgrimage to Rishikesh, Norman writes. If the Maharishi’s teachings had given him a sense of purpose he’d never found with the Beatles, she felt they also “took some of the lightness out of his soul.”

Norman shows how Harrison’s “inner peace” often gave way to “outer scratchiness.”

Harrison once yelled at an airplane cabin attendant who had asked him if he wanted anything.

“F*** off,” George snapped, “can’t you see I’m meditating?”

A professional associate remembers three Georges.

“One was friendly, funny and gossipy; another was uptight, hypercritical and given to witheringly sarcastic personal remarks; the third was either chanting under his breath or delivering ‘spiritual rants.’”

Harrison’s mood wasn’t helped by a long-running lawsuit that eventually found him guilty of plagiarizing portions of “My Sweet Lord” from “He’s So Fine,” a 1963 hit by the Chiffons.

Making history

In 1971, Harrison gathered a few “friends” (including Ringo, Dylan, Clapton and Shankar) to raise awareness and funds in rock music’s first-ever supergroup relief concert/recording/film, the Concert for Bangladesh.

But once again, legal battles over song copyrights and other issues snarled the concert’s funds for years, and mismanagement led to a big bill with the IRS.

In later years, he faced more lawsuits after missing contracted deadlines for solo albums, further alienating him from this material world.

Harrison found laughter in his friends.

He grew close to the British comedians in Monty Python’s Flying Circus. He later would provide funding for some of their films. Harrison also enjoyed the company of his fellow Traveling Wilburys (Bob Dylan, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison and Tom Petty).

Harrison died Nov. 29, 2001, in California, surrounded by images of Hindu deities and clouds of incense, and accompanied by chanting holy men.