The evangelical narrative of one of America’s Founding Fathers continues to be so historically inaccurate that a duo of authors has released an updated version of their book defending the real legacy of Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson definitely was not a proponent of Christian nationalism, said Warren Throckmorton, co-author of Getting Jefferson Right, the second edition of a book first published in 2012.

Warren Throckmorton

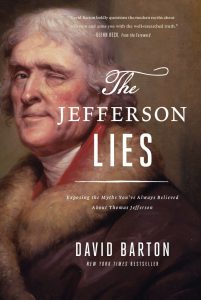

Throckmorton and colleague Michael Coulter first wrote to debunk the widespread inaccuracies of amateur historian David Barton, who the month before had published The Jefferson Lies: Exposing the Myths You’ve Always Believed About Thomas Jefferson. In that book, as in Barton’s oft-quoted works, he fabricated a history of Jefferson that serves the narrative of Christian nationalism.

The inaccuracies were so egregious that Thomas Nelson publishers pulled the best-selling book, explaining: “Our conclusion was that the criticisms were correct. There were historical details — matters of fact, not matters of opinion — that were not supported at all.”

Barton still influential

Barton — whose work has been criticized by both conservative and liberal historians — continues to be a driving force among evangelicals who claim America was founded as a “Christian nation.” He routinely reshapes Jefferson’s story to support that claim.

Also in 2012, readers of the History News Network voted Barton’s book the least credible history book in print — although that honor nearly went to Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.

Calling attention to the dangers of Barton’s book on Jefferson largely emanated from Throckmorton and Coulter, both professors at Grove City College in Pennsylvania. Throckmorton recently retired as a psychology professor. Coulter continues to work as a professor of political science and humanities.

In a normal world, a self-proclaimed historian who published a book so full of errors that the publisher pulled it would not be given any more platforms. But not so with Barton, who continues to influence evangelical leaders.

For example, the conservative legal group First Liberty Institute — famous for its role in cases such as that of high school football coach Joseph Kennedy — recently hosted a nighttime tour of the U.S. Capitol that was led by Barton. The group was joined at one point by new Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, who like Barton contends America was founded as a “Christian nation.”

First Liberty Institute’s Kelly Shackleford, with David Barton standing next to Speaker Mike Johnson.

And Family Research Council — the Focus on the Family advocacy spinoff in Washington, D.C. — continues to publish a video tour of the Capitol narrated by Barton, even though scholars have detailed the factual errors in Barton’s narration.

In 2013, Throckmorton assembled a group of 33 social scientists and historians to review the FRC video. Those conservative scholars concluded the video contained “false and misleading information.” Yet FRC did not stop publishing the video for another nine months — until the scholars threatened to go public with their critique.

Throckmorton has documented correspondence with an FRC official who said he was “well aware of the historical problems” with the video. Yet it remained online.

Only after the threat from the scholars to go public with their critique did the video get pulled from public view — only to reemerge later with a few minor edits but still full of inaccuracies. Throckmorton has detailed those problems on his blog.

In further correspondence with an FRC leader, Throckmorton was told no further changes would be made because Barton has so many followers.

“You eventually don’t have religion. Winning at politics is your religion.”

“Despite the stated reverence for truth in evangelical circles, when it comes to politics, Barton’s got something there,” Throckmorton explained in an interview this week. “If you’re a political entity, you don’t admit errors. It’s all about politics, it’s not about religion. That’s another danger of bringing politics and religion together: you eventually don’t have religion. Winning at politics is your religion.”

The threat returns

After the flurry of response to their work in 2012 and 2013, Throckmorton and Coulter thought the threat of Christian nationalism might be waning. They thought they had achieved some modicum of success in exposing Barton’s fake history and Christian nation narrative.

But they were wrong. Driven in large measure by Trumpism, Christian nationalism instead has surged.

“We started this very casually after Barton brought out his second edition,” Throckmorton said. “He claimed to rebut us.”

“We started this very casually after Barton brought out his second edition,” Throckmorton said. “He claimed to rebut us.”

That second edition, not published by Thomas Nelson but instead self-published by Barton, includes a section addressing his critics. The book’s Amazon listing claims the first edition of the book was pulled because of “political correctness.”

Now, Throckmorton and Coulter believe they need to set the record straight once again.

“Christian nationalism is on the rise, and we felt the book would be timely if we brought it back out to respond to Barton.”

“Christian nationalism is on the rise, and we felt the book would be timely if we brought it back out to respond to Barton. … This book represents kind of a completion of that first book. We also take on the newer strain of Christian nationalism represented by the Stephen Wolfe book The Case for Christian Nationalism.”

Wolfe, a young Reformed scholar, differs from Barton in his approach, Throckmorton said. “Barton tries to evangelicalize Jefferson. Wolfe tries to say Jefferson wasn’t very important to church-state policies at that time.”

What Jefferson actually said

To claim the nation’s founders intended to give preferential treatment to Christians requires either ignoring or rewriting Jefferson, the professor said. Jefferson coined the term “wall of separation” between church and state in a letter to a group of Baptists in Danbury, Conn.

But it’s not just that one letter that makes Jefferson’s case for religious diversity, Throckmorton said.

“Jefferson wrote the statute for religious freedom in Virginia. Yes, Jefferson was in France when the Constitution was ratified and went out to the states, but he wrote at least 27 letters urging at least 15 people to include a Bill of Rights including religious freedom. What kind of religious freedom? Of course, the same kind of religious freedom they had in Virginia. He said very clearly in his autobiography that didn’t include just Christians.”

“This group of people, most of them from states with religious establishments, said we will have no religious establishment.”

There’s also the larger witness of the Founding Fathers, he added. “Its important to recognize that the Founders, there were a lot of them, and they disagreed. What we have to look at is what did they do together. … And what they did together was pretty phenomenal. … This group of people, most of them from states with religious establishments, said we will have no religious establishment. … What they did together is what we’ve got, and that’s what we’re supposed to live by.”

Influenced by Baptist upbringing

For Throckmorton, exposing the lies of Barton and others of his ilk is a result of his Baptist upbringing. “Soul liberty is one of the Baptist distinctives we were taught,” he said.

When he became aware of the modern-day threat of forced religious conformity being pushed as a political agenda, the professor and counselor started digging in to find the source of these ideas.

“I had not given a lot of thought to bigger issues than therapy … the narrow issues I was concerned about. But I started to think about the bigger picture issues like the relationship of church and state and how Christians should think about the separation of church and state,” he explained. “Suddenly, I remembered my Baptist roots.”

David Barton

In his research, one name kept reappearing: David Barton.

“I didn’t know for sure who David Barton was. I started to read his stuff and read some of these stories about Thomas Jefferson and John Adams and how they were more evangelicals than anybody realized. … A lot of it was made up. I started to debunk these stories for myself. A lot of people already had debunked them. I wasn’t the first.”

However, proving Barton wrong “was so easy even a psychologist could do it,” he quipped. “He was twisting things around to make it sound like something happened that didn’t happen.”

He naively thought if people simply knew the truth it would make a difference — even if Barton were shown his errors he would change. That was not to be, however.

How a respected Christian publisher like Thomas Nelson could be duped by Barton remains a mystery.

Proving Barton wrong “was so easy even a psychologist could do it.”

“They had gotten recommendations from people they trusted that he was maybe a little out there … but they were looking for someone on the right who was provocative to write a book. It was Barton’s idea to write about Jefferson. They just assumed he wouldn’t omit, cut right out, parts of laws to make his case. He said Thomas Jefferson said it was illegal for him to free his slaves, but it wasn’t. Thomas Nelson just trusted that an author wouldn’t do that.”

The evangelical recasting of Jefferson isn’t just about religious liberty but also about slavery.

“Barton tries to whitewash Jefferson’s entire record as an enslaver,” Throckmorton said. “We don’t let that go. We talk about the fact that Jefferson could have freed his slaves but that was a consequence of his own choices. … He sent slave catchers after runaways. He in a sense bred slaves. He said when female slaves had children it was a profit to him. … It’s despicable.”

Barton has refused to admit his errors, and he has powerful enablers, Throckmorton said.

“One of the cases I make is there is a conspiracy of silence. A lot of the rightwing influencers know there are problems with Barton’s stories, but he’s too useful to them, to the policies they want to enact, so they don’t do anything about it.”