The histories we tell ourselves about our churches and denominations are important. They shape organizational identities and give greater meaning to the work churches and denominations conduct in the wider world.

When those histories become deeply engrained, they can morph into hagiographies that embellish the lives of crucial founders or events. They also can lead to myths that prohibit us from rightly seeing ourselves and the institutions we are so committed to supporting and sustaining. History needs the chance to grow, to change and to question assumptions.

Moderate and progressive Baptists in recent years have been willing to examine the legacies of white supremacy and racism that shaped the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention. We lament and sit with the uncomfortable reality that our white denominational ancestors were white supremacist slave holders.

After all, for many of us, the SBC is no longer our denominational home, meaning such interrogation remains a little bit removed from ourselves.

Such historical interrogation is important and fruitful. For moderate and progressive Baptists in groups like the Alliance of Baptists and Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, such interrogations never seemingly address their own founding narratives. It is perfectly comfortable to address the racism and white supremacy that shaped the SBC’s founding, but addressing the problematic legacies that established the Alliance and CBF is a little different.

“We remain addicted to stories of the Baptist Battles of the 1980s that shaped the histories of the Alliance and CBF.”

At the same time, we remain addicted to stories of the Baptist Battles of the 1980s that shaped the histories of the Alliance and CBF. I should know, I always have been enamored by the stories and the people in them. Stories like Roy Honeycutt standing up for his principles and declaring Holy War during a convocation address in 1983. The sudden and drastic “fall” of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in 1987. The slow fall of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Russell Dilday being locked out of his office at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

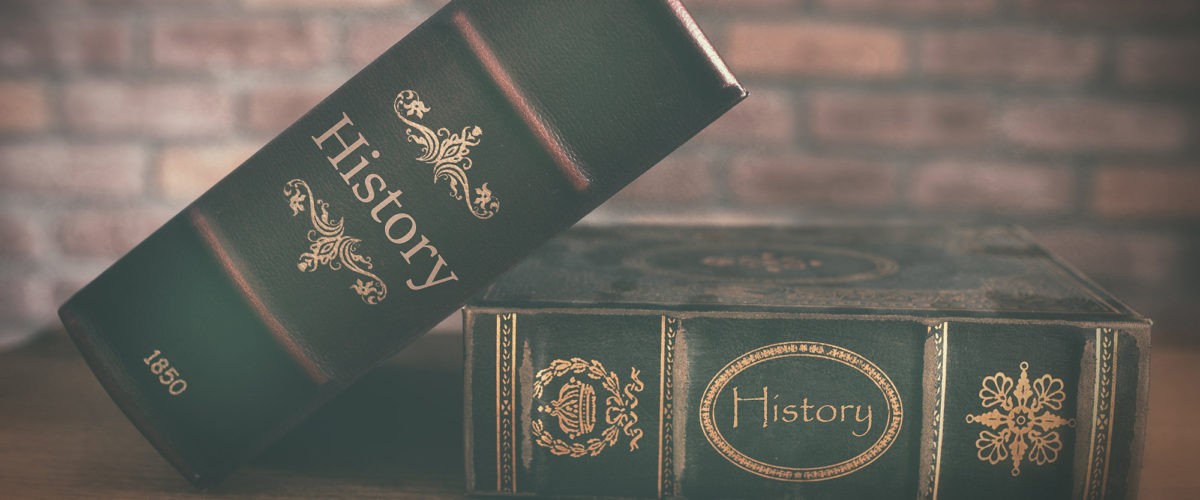

Paul Pressler (left) and Paige Patterson, architects of the SBC takeover, sit at Cafe duMonde in New Orleans June 9, 1990, comemmorating their meeting at the same spot 20 years earlier to conceive the plan to gain control of the nation’s largest non-Catholic denomination. (Photo by Thom Scott)

Perhaps not everyone knows all the detailed stories, but we know the gist. Conservatives put in motion a 10-year plan to elect conservative presidents to the SBC who would control the Committee on Nominations. From there, conservatives could pack the boards of nearly all Southern Baptist agencies.

The moderate faction was unable to withstand the conservative offensive and would leave the SBC to found groups like the Alliance and CBF. These individuals stood up for conscience and religious freedom. With a little historical hindsight, we might even admit that it was a losing battle from the beginning.

Revisionist Southerners also claimed with a little bit of hindsight that the Civil War was a losing battle. The Cult of the Lost Cause would attempt to reframe the conflict as the war of Northern aggression or the war for states’ rights. Rather than remember the South for its racism and slavery, the South was remembered for its honor and bravery. The South allegedly knew they had no chance of success in this war, but they fought for their honor anyway.

Slavery was merely a secondary issue for disciples of the Lost Cause. The Civil War was not the war against slavery, it was the war of Northern aggression. Enslaved persons and their masters had good relationships, so the myth goes. Generals like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson became larger than life figures, known for their Christian piety and Southern honor.

The SBC was at the center of promoting a lot of these narratives, carrying them forward throughout the period of Reconstruction and beyond. While Methodists and Presbyterians found ways to heal the rift slavery and the Civil War created in their denominations, Southern Baptists have remained committed to their independence. They remained committed to this Lost Cause way of thinking.

Framing the battle

The historiography of the Baptist Battles from the 1980s has a similar historiographic dynamic with regards to how you simply name the conflict. Conservatives have characterized the events of the 1980s and ’90s as the “conservative resurgence” in the SBC. Moderates characterized the events as the “fundamentalist takeover.”

The language of each retelling helps delineate the ideological tradition of the history much like the Civil War and the war of Northern aggression.

“When the Southern Baptist Convention voted to expel two churches for having women pastors this summer, we quickly returned to the fray, telling our war stories.”

Moderates lionized those who fought the good fight, those who helped create organizations like the Southern Baptist Alliance and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. They established schools like Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond among other new seminaries. Indeed, they helped create Baptist News Global, originally known as Associated Baptist Press. All the while, moderates rewarded and valorized those who stood up for conscience’s sake and were forced out of their jobs and livelihoods because of their theological position.

To this day, moderate and progressive Baptists continue to valorize and celebrate those who remember the days of the SBC. The Baptist Battles sell. The conservative takeover draws in the crowds for fundraising appeals. We create endowed academic chairs for former denominational leaders to retire into. We create well curated and scripted podcasts about the lives of former Southern Baptist faculty. We pack out lecture halls and webinars to hear from those who fought the so-called “good fight.” We have named scholarships and even a school, lionizing the fallen.

When the Southern Baptist Convention voted to expel two churches for having women pastors this summer, we quickly returned to the fray, telling our war stories. We remember when. This is not news. This is tradition in the SBC.

For recovering and formerly Southern Baptist persons, relitigating the good ole days of the SBC is a lost cause.

The 1985 SBC annual meeting in Dallas, which registered the highest attendance in denominational history.

Quest for power

Conservatives say this battle for the SBC was fought on the grounds of theological fidelity. Moderates claim the heart of the conflict was power and not theological conviction. We quickly buy into this argument and accept it on its face that the leaders of the conversative camp were not concerned about theology, they were only concerned about power.

Maybe they were and maybe they were not. Such a rhetorical move, however, masks the intentions of the moderates. They, too, craved power.

As often as we tell our story, we also can tell our story another way.

“As often as we tell our story, we also can tell our story another way.”

Those who founded our moderate and progressive white Baptist movements in the South fought tooth and nail for the right to control a denomination built on the legacy of slavery and white supremacy. Many of them gladly went to receive educations or to teach at schools that upheld this white supremacy. They mourned when they lost control. They left sore losers, crafting narratives to demonize the other side when they were just as invested in the success and longevity of a white supremacist denomination they hoped to lead — regardless of whether they wanted to uphold it or redeem it.

For quite a while, I have wondered about how we might tell this story, particularly when so many formerly and recovering Southern Baptists continue to control levers of power in moderate and progressive Baptist life. Power was, after all, the primary objective.

As a historian of American religion, and one who happens to also be Baptist, these stories will always be with me. I, like many of you, remain addicted. It’s time we start telling them a little differently and privileging other and newer perspectives.

On myths and women in ministry

One of the founding myths of both the Alliance of Baptists and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship is that these denominations were begun to support women in ministry. For the better part of a decade, I have continued regularly to read and hear this assessment throughout Baptist life.

When the SBC expelled two churches this summer for having women as pastors, it only filled moderate and progressive Baptists with righteous indignation. It offered a point of clear conviction. A point that is just as easily muddled when one realizes that as of 2021, only 7.4% of CBF congregations have a woman as a senior pastor or co-pastor.

“We have been telling ourselves a lie about the history of groups like the Alliance of Baptists and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.”

Part of the problem is that we have been telling ourselves a lie about the history of groups like the Alliance of Baptists and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. Neither group organized with the express purpose of affirming women in ministry.

Alliance beginnings

When the leadership for what would become the Alliance of Baptists gathered in December 1986, women in ministry was only one of many issues they were concerned about within the SBC. Alliance founders were tired of fighting the Baptist Battles in the SBC. Through my own research and conversation with many of these founders, they all were insistent the Alliance supporting women was not a given.

Most of the Alliance’s early meetings were dominated by men. At the first meeting, only four women were present: Edna Langley, Sarah Wilson, Nancy Hastings Sehested and Susan Lockwood.

Nancy Hastings Sehested and Susan Lockwood

The earliest Alliance gatherings coincided with the Southern Baptist Home Mission Board’s decision to prohibit any financial assistance to be sent to churches with female pastors. Some of the men wondered whether the Alliance could rally people around this issue. Lockwood and the rest of the women present objected to the idea of using the issue of women in ministry “as a means to reach larger ends.”

The early women of the Alliance were more interested in fighting for the organization to have equal representation on the young denomination’s board than creating a political football out of the issue of their vocational calling. The first Alliance board had 18 men and only three women.

One of those three women was Ann Thomas Neil, a former Southern Baptist missionary. Neil pushed the early Alliance on equal representation in the Alliance for women. She recalled on numerous occasions being asked by male board members in unfriendly tones, “Just what is it you women want” from this new organization?

At one board meeting, Baptist Women in Ministry requested $15,000 to help publish their newsletter. The Alliance executive committee approved $1,000. Later in the meeting, some men proposed and approved sending an unprompted $5,000 to help the predominantly male faculty of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary with legal fees.

Ann Neil

When Neil protested, another man interrupted her saying, “Can’t you see the blood of these faculty members flowing here on the floor?” She quickly responded, “Yes, I can; but can you see the avalanche of blood of women that has been flowing for nearly 2000 years?”

She was later told how “offensive and unappreciated (her) words” were.

While Alliance congregations today are recognized as having some of the highest percentages of female clergy in Baptist life, this is not the whole narrative. Telling a narrative that claims the Alliance supported women from the start erases the blood of women like Sehested, Lockwood and Neil, who pressed the organization not to use women as a political tool. Instead, these women sought an equitable organization in which women had an equal seat at the table.

CBF beginnings

Much like the Alliance, CBF did not come into existence supporting women in ministry. While leaders of the Alliance tired of fighting the Baptist Battles in 1987, CBF represented moderates and progressives who continued fighting into the early 1990s. For all those who fought, the “battles” were waged politically, seeking to leverage the power of the denomination toward whatever ends.

The goal of the politically savvy moderates in the 1980s never was an affirmation of women in ministry. Such an affirmation would have assuredly failed at the massive summer annual gatherings. Instead, moderates sought for the SBC to acknowledge the freedom of the local church to call a woman to serve as pastor. Baptist principles were put over and above every woman in the SBC. The only way a woman is affirmed in ministry is if a congregation was willing to call her.

When the Alliance and CBF considered the possibility of merging in the early 1990s, the twin issues of women and LGBTQ inclusion were the sticking points. Cecil Sherman, a moderate hero and first executive director of CBF, recalled years later the Alliance’s fourth president, Ann Quattlebaum, was to blame. He explained Quattlebaum “was ready to compromise Baptist polity for the sake of the women’s issue.” CBF, according to Sherman, would not make this compromise.

Women less important than Baptist polity

This was the mindset of so many moderate and progressive Baptist leaders in the 1980s and ’90s who helped shape both the Alliance and CBF. Women are less important than fidelity to Baptist polity. Women are less important than the power men held in Baptist life.

Cecil Sherman, 1995

No wonder so many women question their calling in Baptist life. Our moderate and progressive forebearers were clear: You were only affirmed if you received a call. These moderates, like Cecil Sherman, took no leadership in affirming women in ministry. He simply did not oppose it. While men remained affirmed in their vocational calling whether a church called them or not, women’s affirmation was contingent upon whether a church would call them to the pulpit.

I make no claim that this is the “right” or “correct” way to tell the history of the Alliance or CBF, but it remains one way to tell the story. History is far more complicated than singular narratives.

When we only tell the story that the Alliance and CBF were founded to support women in ministry, we do a disservice to ourselves to prop up men from the generation who fought the “good fight” of the Baptist Battles of the 1980s.

“While many of those individuals may have come around on the issue of women in ministry years later, that does not change history.”

While many of those individuals may have come around on the issue of women in ministry years later, that does not change history. It does not erase how those individuals perpetuated the problem.

And while some may have sought to correct the error of their ways, we must ask how long they clutched onto power in order to control how the error was corrected.

Moderate Baptists, apologies and race

In the summer of 2020, as the pandemic lockdown wore on, Americans were unable to turn away from the horrific murders of two Black men — Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd. The videos of Arbery and Floyd’s murders circulated social media, spurring public outcry and protests around the country.

I noticed it also spurred a turning inward for many moderate and progressive white Christians. At a time so many individuals were continuing to mask and social distance, this inward turn took the form of studying history to better understand the problems currently facing American society regarding the subject of race.

Numerous moderate and progressive Baptist congregations established virtual groups to study various curricula and recent books addressing the history of race in America.

Robert Jones’ White Too Long, became a standard text for many of these groups. Jones’ work addresses the SBC’s legacy with regard to slavery, racism and white supremacy in detail. It along with other texts and studies shined an important and necessary light on Baptist roots in the United States.

For many former and recovering Southern Baptists who continue to identify as Baptist, however, focusing on the Southern Baptist Convention is a convenient foil. Yes, groups like the Alliance of Baptists and CBF do emerge out of the Baptist Battles and share this history with the SBC. And yes, the SBC’s history is the history of the Alliance and CBF.

Focusing on the history of the SBC alone, however, can easily eclipse an examination of the founding eras of the Alliance and CBF that failed to adequately address the racism and white supremacy that permeated the SBC.

Alliance beginnings

In December 1986, a group of six white men gathered to put together a statement that would become the founding covenant of the Alliance. “In a time when historic Baptist principles, freedoms and traditions need a clear voice,” this statement sought to give the Alliance seven principles to which the new organization would commit itself.

The document included commitments to the freedom of the individual and of the local church, a commitment to ecumenism as well as religious liberty. It also included a commitment to “the proclamation of the Good News of Jesus Christ and the calling of God to all peoples to repentance and faith, reconciliation and hope, social and economic justice.”

At the first gathering of the Alliance at Meredith College in 1987, the Alliance received a proposal for an additional commitment. Recognizing the issue of race was not present in the document, Charles Worthy proposed adding a statement committing the Alliance to “the equality of the races and unity of the human race, and we wish to be a multi-racial, pluralistic body.”

“Alliance founders forgot to address race.”

The amendment was considered and referred to the board of directors. As Alan Neely, an Alliance founder, recalled, the proposed change was forgotten and never discussed. The issue of race was forgotten. Alliance founders forgot to address race.

A few years later in 1990, the Alliance sought to address the issue of race. It passed a statement titled, “A Call to Repentance,” in which the organization acknowledged white Southern Baptists never had repented for the sins of slavery. The statement sought to acknowledge and repent of the efforts to condone and perpetuate “the sin of slavery prior to and during the Civil War.” The statement also sought to challenge the SBC to make its own statement at the upcoming SBC annual meeting in New Orleans. No such statement was adopted.

Rodney King after the acquittal of the four LAPD officers who struck him with their batons on March 3, 1991. (Photo by Bill Nation/Sygma via Getty Images)

CBF and race

Two years later, in the wake of the brutal beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police, the newly formed CBF felt compelled to adopt a similar statement of repentance. This statement was modeled on the Alliance’s statement — copying sentences, structure and language. This was a contentious vote for CBF in its early history. The “Statement of Confession and Repentance” passed by a “narrow margin,” according to Baptist Press.

Those opposing the statement were reportedly opposed to CBF passing any statement and not simply opposed to the statement of repentance. The following year, CBF adopted a new rule that “prohibited resolutions and similar motions from being introduced from the floor of an assembly” meeting.

From one perspective, the challenge of addressing race would inhibit the denominational body from adopting a statement on any issue.

In 1995, the SBC would pass their own statement of apology for the sins of slavery, also similarly structured to the statements of CBF and the Alliance.

Different yet the same

While we can understand this to be a history worth celebrating that led to white Baptists from the South apologizing for the legacy of slavery and white supremacy, we also can understand this history from another perspective. Given that each statement is quite similar in structure and language, divergences are significant in marking denominational identity.

The SBC concluded its apology with a pledge to recommit to the Great Commission, whereas the Alliance and CBF concluded with a pledge to “seek out” greater participation from Black Christians in their respective organizations.

For the young Alliance and CBF, we can understand these statements as clarifying the type of white Southern Baptists the two organizations sought to be. They were less any type of meaningful apology and more statements of identity distinguishing the two denominational bodies from the SBC.

From this perspective, both statements’ concluding goal of soliciting greater African American participation reads as self-serving.

History is never static

History is challenging because it is never static, and it is never singular. Yes, the formerly and recovering Southern Baptists who helped establish the Alliance and CBF were trailblazers in their willingness to offer statements of apology regarding the legacy of slavery, racism and white supremacy that shapes the white Southern Baptist experience. At the same time, we also can understand the history and legacy of these apologies as hollow and self-serving.

Both realities can be true. The challenge is how we hold both realities together at the same time.

When we continue to view the Baptist Battles of the 1980s as good conscience-following “moderates” versus bad power-hungry “conservatives,” we fail to recognize those “moderates” were power hungry too. History shows they forgot about issues of race or only narrowly approved of making any statements that addressed race and racism. And when the weight of history evaluates these statements of apology for the sins of slavery and white supremacy, it is clear these statements had very little impact in shaping the organization’s overall trajectory.

May we strive to be better than those who went before us.

Andrew Gardner

Andrew Gardner serves as lecturer in religious studies at LaGrange College. He is a Baptist historian trained with a master of divinity degree from Wake Forest University School of Divinity and a Ph.D. from Florida State University.