One of the factoids for which 2023 will be remembered is the TikTok hashtag #romanempire. This was the year a generation of women (much to their surprise and bemusement) learned the men in their lives think about ancient Rome regularly if not daily.

Saturday Night Live memorialised the trend as a musical sketch starring Jason Momoa. In recent days, the hashtag has resurfaced again in several “Top Memes of 2023” lists.

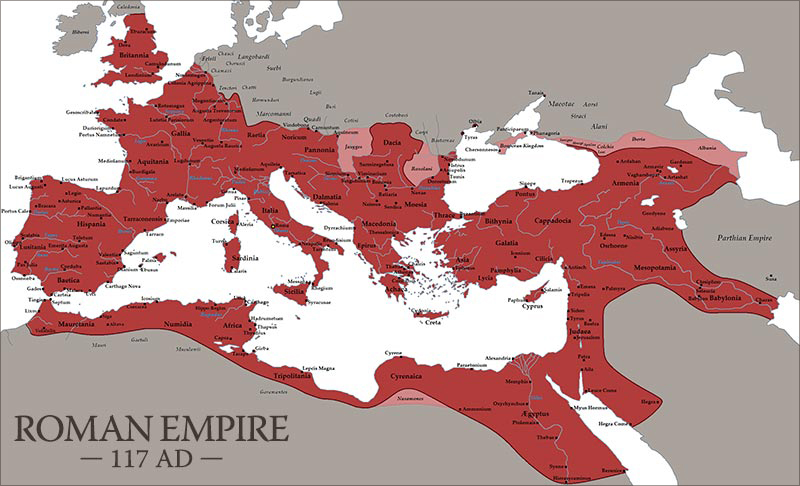

As a Ph.D. student working on Luke-Acts, I think about Rome fairly often, especially now that I live in a country that once was a Roman province. (Although the Scots will proudly tell you the Romans never wrestled Scotland (Caledonia) into submission!) When we have the time, my wife and I can walk our dogs on a bona fide Roman road that runs behind the cottage we let. Thinking about Rome seems natural.

No matter which side of the #romanempire craze you fall on, however, Advent is one time of the year when all of us who wait expectantly for news that Christ is born in Bethlehem should think about Rome. Because Luke wants us to.

The Gospel of Luke and Rome

Luke intentionally frames his telling of the Christmas story within the context of Roman imperial rule. He did not have to set such a frame around his narrative. Matthew tells of Jesus’ birth perfectly well without any mention of Caesar or his census. The fact that a decree issued from the hand of Augustus forms the backdrop for the news the angel brings means Luke wants us, his readers, as well as the shepherds to hear this good news within this particular context:

“Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

Suddenly a great company of the heavenly host appeared with the angel, praising God and saying,

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.”

When the angels had left them and gone into heaven, the shepherds said to one another, “Let’s go to Bethlehem and see this thing that has happened, which the Lord has told us about.” (Luke 2:10-14)

Some biblical scholars downplay the significance of Luke’s mention of Caesar Augustus, the strongman who transformed the Roman Republic into a military dictatorship while claiming to restore the Republic to its former glory. These interpreters see the reference to the census as nothing more than an ancient historian’s device for setting the chronology of events.

Why the census reference matters

The census is that; but it is more than that. If, years from now, someone composed a story about a child who would grow up to bring true healing and wellness to the world and specified this child was born during the Obama administration, we would rightly read that remark as more than a time stamp.

Just as health care reform defined the Obama years in the United States, terms like “peace” (pax/eirene) and savior (salvator/soter) were hallmarks of Roman imperial rhetoric for Augustus and his successors.

Just prior to Jesus’s birth, an inscription found in Priene (in what is now western Turkey) establishes Augustus’ birthday as the start of the new calendar year for that region. Sometimes referred to as “The gospel of Augustus,” the inscription explains the reason for this significant change: Providence sent Augustus, the (adopted) son of the divine Julius Caesar, as a savior to end war and arrange all things. The new year will begin on Augustus’ birthday because the day he came into the world marks the beginning of the good news (euangelion) that has come into the world through him.

Around the time the Priene Inscription was engraved, the Roman Senate declared an altar to peace should be constructed and dedicated to Augustus in Rome upon his return from successful campaigns in Spain and Gaul in 13 BCE. The Ara Pacis was completed and consecrated four years later with a lavish procession and ceremonies.

In his autobiography, the Res Gestae, Augustus further trumpets his role in establishing peace, boasting that during his reign the Senate ordered the doors of the Temple of Janus to be closed three times, thus symbolising peace on land and sea throughout Rome’s domain. In all of Rome’s expansive history, these doors had been closed only twice before.

Closer to Luke’s own time, the emperor Vespasian, queller of the Jewish Revolt of 66-70 CE and founder of the Flavian dynasty following the civil war of 69, constructed a larger, grander temple to the goddess Pax in the center of Rome. He also minted coins showing his face on the obverse and Pax on the reverse. The messaging was clear: the peoples of the empire owed their safety and prosperity to the emperor’s victories over Rome’s foes, both internal and external. Peace was his benefaction and glory his reward.

“For the heavenly host to sing glory to Israel’s God in the highest rather than to Rome’s Caesar on earth, is a subversive act of storytelling.”

In such a political milieu, for Luke to redirect and redefine this language of salvation and peace by wrapping them around the newborn Jewish baby Jesus; for the heavenly host to sing glory to Israel’s God in the highest rather than to Rome’s Caesar on earth, is a subversive act of storytelling. As was plainly evident from history and experience, even in Luke’s time, the emperor’s peace was tentative. It was enforced through intimidation, propaganda and violence. It suppressed division rather than forging unity.

The next disturbance lay just around the corner. Under Augustus, the Senate may have closed the doors of Janus three times. The unspoken reality is that they reopened those doors three times as well. Luke’s proclamation is that Jesus offers a different, more resilient and enduring form of peace and salvation.

Imperial power

Thus, in the second chapter of his Gospel, Luke invites his audience to weigh the claims of imperial power and measure them against the height, breadth and depth of God’s promises to God’s people fulfilled in Jesus. In Bethlehem’s manger, the angel declares good news (euangelion) that is cause for great joy among all people, subjects of Caesar and children of Abraham alike. Good news that Jesus himself will later expand and clarify: Good news for the poor, liberation for the captives, recovery of sight to the blind, release for the oppressed, proclamation of the year of the Lord’s favor. Good news that will enthrall and transform centurions such as Cornelius, Pharisees such as Saul of Tarsus and multitudes in between.

“Luke’s Christmas story is so much more than a story for Christmas.”

Luke’s Christmas story is so much more than a story for Christmas. It’s a story for all times and places, wherever people are tossed about and weighed down, “optimized” and commodified, exploited for their labor and their allegiance by earthly powers and the markets and structures created by those powers in pursuit of their own profit and aggrandisement. Nevertheless, it’s a story rooted in one specific time, one particular socio-political context.

That’s why we need to pay attention to Luke’s method of presentation as much as what he presents. Luke uses the birth of Jesus as a lens through which to critique the power dynamics and political talking points of his context. We cannot fully comprehend the good news Luke illustrates without understanding his context and likewise examining our own socio-political context through the lens of Jesus’ gospel.

Rome for a day

Such critique is what the TikTok hashtag #romanempire is lacking. The men who think about Rome as they go about their day are only thinking about Rome as they know it through the popular imagination: through sword and sandal movies like Gladiator, programs on the History Channel, and videos on YouTube.

Painting of Caesar Augustus

Yes, ancient Rome — the Rome Caesar Augustus ruled and helped shape — left marvels of architecture and engineering in its wake. Aqueducts that transported water over many miles powered simply by gravity. Concrete that could be set under water and “heal” itself. Amphitheaters like the Colosseum, temples like the Pantheon — all constructed with elegance and precision without benefit of motorized heavy machinery, computers or even algebra. After two millennia of wear and tear, these structures are still truly wondrous, even as mere ruined shadows of their original designs.

Yet, behind these wonders of achievement lay a social and political order that was profoundly elitist. Only the wealthy few truly enjoyed the spoils of empire, such as the preserved villas we can tour in Pompeii. Most urban Romans subsisted on bland diets and lived in dark, cramped, smelly apartment blocks called insulae. In the countryside, large landowners gobbled up small(er) farms. Wealth was concentrated in the hands of a select few, and power with it.

Along with military victories and the closing of temple doors, in the Res Gestae Augustus further boasts of the hundreds of millions of sesterces he spent providing bread and circuses for the Roman people. It sounds lavishly generous until you realize these are essentials and entertainments the people could not afford for themselves because so much of the empire’s great wealth was under one man’s control. Many people were poor, and a good many more were slaves. Life in the Roman Empire was often harsh and brutal in ways obscured by the sheen of Rome’s marble façades and the gleam of the legionnaire’s armor.

Rome and the USA

The parallels between ancient Rome and modern America are many. Our achievements are undeniable. I live an ocean away, yet I am surrounded by American brands and influences wherever I go around the UK. America’s industrial, economic, military, scientific, technological and artistic innovations have reshaped life on planet earth.

However, America remains a nation of contradictions. The language of our Declaration of Independence is famous the world over; and yet many other countries have done a better job putting those self-evident truths into practice. The “American Dream” is reeling if not dying.

In recent surveys of social mobility among the world’s nations, the United States does not even rank in the top 20. The wealth divide between American’s rich and poor is staggering. For a nation founded, in part, on the “pursuit of happiness,” Americans also are not especially happy. And then, of course, there is the malignant legacy of American chattel slavery that continues to infect all strata of life in the United States.

One reason America has stopped progressing in ways that its global peers have not is that many Americans are engaging in the same kind of popular, uncritical reverence for America that TikTokers express for Rome. Especially concerning is that many of these same Americans are professing Christians.

Terms such as “freedom” and “patriot” are bandied about along with the name of Jesus, but this “Jesus” is not a Lukan lens for understanding or critiquing these staples of American political rhetoric or their accompanying power structures. This “Jesus” is a populist mascot for cheering on a socio-political agenda that does not have its origins anywhere near the manger.

“The poor cannot receive good news when we pander to the whims and delusions of the rich.”

It’s an agenda that bans books and sanitizes curricula, not only shying away from critique but forbidding it. It’s an agenda that, despite the frequency with which the name of Jesus is evoked, stymies the gospel Jesus expounded in Luke 4. The blind cannot receive their sight when we don’t want them to see. Prisoners cannot be freed when we deny their captivity. The poor cannot receive good news when we pander to the whims and delusions of the rich. We cannot proclaim the liberation of Jesus’ gospel if we do not use that gospel to test what we are served through our various screens and feeds, including the pulpits of our churches.

On Christmas night, Jesus will once again be born unto us. He will thus be born into our socio-political context. He is the light shining in the darkness, and that light will guide our path. But only if we refuse to leave Christ in the manger. Only if he becomes for us, as he became for Luke (and for C.S. Lewis), the light, the lens by which we see all else.

So don’t leave Jesus in the manger. Don’t even leave Jesus in Christmas. Carry him with you into the new year and let him carry you into the election year that lies ahead. There will be much to weigh, critique and resist in Jesus’ name.

Todd Thomason

Todd Thomason is a gospel minister and justice advocate who has served as pastor of churches in Virginia, Maryland and Canada. He holds a doctor of ministry degree from Candler School of Theology at Emory University and a master of divinity degree from McAfee School of Theology at Mercer University. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in New Testament and Christian origins at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. In addition to Baptist News Global, Todd writes at viaexmachina.com.