In 1980, legal scholar and critical race theorist Derrick Bell penned his pioneering article, “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma” in Harvard Law Review. In it, Bell tackled a controversial and difficult question: In the wake of Brown v. Board — the Supreme Court decision ruling school segregation unconstitutional — why was the public school system failing so many Black children, and failing so miserably?

Jacob Randolph

Bell concluded a reappraisal of Brown was needed, taking into account, in the words of Jamel Donnor, the ruling’s “limited impact and subsequent retrenchment” in the face of white flight, local board resistance and misappropriation of education funds.

Bell offered an alternative to the prevailing narrative that Brown was predominantly the result of a quickening of the white American conscience. Rather, Bell argued desegregation gradually became expedient for advancing unrelated American causes and bolstering the American post-war identity as custodians of democracy.

In the words of Bell, Brown’s success “cannot be understood without some consideration of the decision’s value to whites, not simply those concerned about the immorality of racial inequality, but also those whites in policymaking positions able to see the economic and political advances at home and abroad that would follow abandonment of segregation.”

“The interests of Blacks in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of whites.”

The larger context of Brown and its stifling could be partially explained by the coincidence of Black concerns and white opportunities, captured in Bell’s theory of interest convergence, the principle that “the interests of Blacks in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of whites.”

Bell points to three possible points of “interest convergence” in the case of Brown v. Board:

- The gradual process of desegregation would, it was hoped, help shift global perception of the United States amid the Cold War.

- Desegregation might provide assurances to Black veterans of World War II who vocally pointed out the hypocrisy of American democratic rhetoric and the relative dignity given to Black expatriates in the Soviet Union.

- Desegregation would allow the Southern economy to modernize, transition from rural to industrial, and increase wealth with new forms of production.

Historian Mary Dudziak confirms Bell’s suspicions with regard to his first two points of convergence. In her article, “Brown as a Cold War Case,” she points to an amicus brief filed by the Justice Department ahead of the Brown hearings. The Justice Department offered but one rationale for ending segregation — not its legal unseriousness nor the suffering of Black American citizens. Rather, segregation should end because “the existence of discrimination against minority groups in the United States has an adverse effect upon our relations with other countries.”

“Racial discrimination,” the brief continued, “furnishes grist for the communist propaganda mills, and it raises doubts even among friendly nations as to the intensity of our devotion to the democratic faith.”

Critical Race Theory’s principle of interest convergence helps explain why segregation of public schools ended when it did, and for reasons not wholly, or perhaps even primarily, related to Black suffering or the aims of Black communities.

Baptists and Brown v. Board

But what does the legal complexity of Brown have to do with Southern Baptists? Put simply, Baptist reactions to and gradual acceptance of the passage of Brown reveal a similar point of convergence, a spiritualized application of interest convergence that mirrored the concerns of the U.S. government and the emphasized public relations concerns of the United States more broadly.

“The moral scandal of Jim Crow became more and more problematic for Southern Baptist missionary efforts.”

With the onset of the Cold War, in the midst of decolonization efforts in Africa, and in the torrent of globalization that came with mass media, the moral scandal of Jim Crow became more and more problematic for Southern Baptist missionary efforts. Southern Baptist leaders urged their congregations to shift their perspective on segregation and racial prejudice. This change in mind came not wholly in response to Black concerns or in the interest of improving material outcomes for African Americans, but rather because letting go of segregation would help Southern Baptists preserve their identity as a mission-minded institution.

In the May 24, 1954, issue of Baptist Press, Southern Baptist leaders weighed in on the court’s decision. Opinions varied. Some, like Christian Life Commission head A.C. Miller, wrote that the ruling was the “inevitable result of social progress” based on Christian teaching. Others, like pastor John Buchanan of Southside Baptist Church in Birmingham, said the decision “complicates and damages relations between races in the South.” Still others were caught in the middle. Herschel Hobbs of First Baptist Church of Oklahoma City conceded the decision was “Christian in principle but fraught with problems of local application.”

Many Southern Baptists were frustrated by the seeming complexity of racial desegregation. But since the court had forced the issue, some leaders sought to entice cooperation and find the silver lining by focusing on the domestic and international ministry opportunities desegregation afforded. Baker James Cauthen, then executive secretary of the SBC Foreign Mission Board, argued the decision was in the SBC’s best interest, as it would “strengthen American influence … and will reduce some obstacles to missionary work among the races.”

Indeed, this was the tack many SBC groups took. In his book, Getting Right with God, historian Mark Newman narrates the legacy of Brown among Southern Baptists. He writes that some in the SBC had seen racism as a sticking point in foreign missions even prior to Brown v. Board. Newman quotes Amos Greer, a missionary and member of Oak Grove Baptist Church in Arkansas, a church that admitted African Americans to its roll in part because “we would look funny talking about foreign missions if we could not do something like this in our own community.”

Local church struggles

The psychological and logistical challenge of loosening white supremacy’s grip seemed debilitating for many church communities. Racial inequality alone proved to be a weak ping on the moral radar of many Southern Baptists. But the opportunity to solve the global PR issue of institutionalized racism — the fact that Southern racism hampered international mission work — was compelling enough reason to accept Brown v. Board for some.

In fact, the issue became a point of emphasis in the work of the SBC Christian Life Commission. In his 1954 report at the annual Southern Baptist Convention, CLC executive A.C. Miller wrote that the costs of legalized segregation had begun to outweigh the benefits, as the United States had risen to become a world power and protector of global democracy. Yet, Miller said, racial segregation posed challenges for U.S. involvement in the United Nations.

Not only that, but Baptist “treatment of minority peoples in our citizenship weakens the witness of our missionaries in other lands even more than in our own.”

Newman reported the CLC even published a pamphlet in 1957 titled “Race Relations: A Factor In World Missions.” In it, the author wrote that news reports of racial discrimination that reached mission fields abroad could “quickly destroy good will and understanding which the missionary has laboriously built up over the years, and may create embarrassments and problems which greatly hinder his work.”

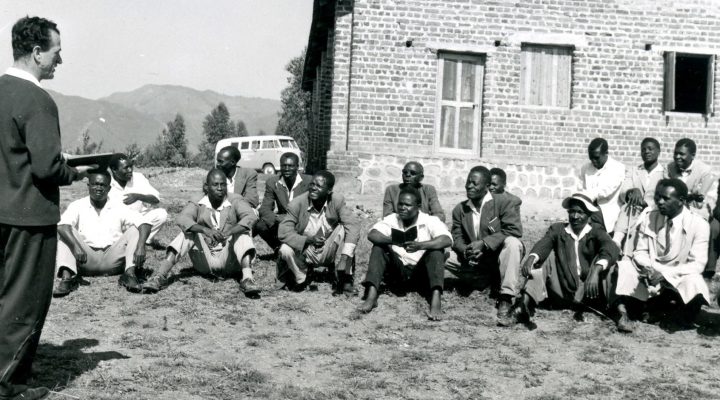

Baptist colleges and seminaries were particular sites of conflict. W.E. Wyatt, a Texas-based missionary to Nigeria, told the Texas Baptist executive board in 1961 that their hesitation on racial integration would prove to be a nuisance to his evangelistic efforts among Africans.

“If we wait until this thing is pushed down our throats,” he commented, “then it is going to be a mark against us.” That same year, more than 800 Southern Baptist college students joined together to support desegregation in their schools. Issuing a five-point resolution, the Texas Baptist Student Union voiced “concern over the damage done to the witness for Christ on the mission field by the prejudiced attitude of Christians in America.”

In 1965, Furman University admitted four African American students. The open admissions policy came in spite of the South Carolina Convention voting to restrict admission to white students. Furman’s board of trustees acted against the state convention’s recommendation because, in the words of board chair Wilbert Wood, “it is right, it is Christian, it is in the best interests of Furman, it is in the best interests of Baptists, and it is in accord with our denomination’s great worldwide program of missions.”

He also warned legal restrictions would affect the bottom line. Refusal to admit Black students would eventually “endanger Furman’s accreditation,” would “result in the loss of many of our best faculty members,” and “would severely hamper the university financially.”

‘All deliberate speed?’

Carole Hovde, a missionary to Liberia, wrote a highly personal piece in a 1968 issue of Commission, an international missions magazine of the SBC. Hovde told the story of a Liberian student’s encounter with a missionary.

“You are from the United States,” the student shouted. “There you look down on us! Why are you telling us about Christ? There is segregation in your country. You must be pretending!”

A year later, Rudolph Wood, a missionary to Belgium, said in an interview that the greatest boost to Southern Baptist missions would be “without reservation, to tap the potential for Christian work stored in the Black population.”

“A decade after the 1954 decision, SBC missionaries were still using the pressures of the mission field to chide Southern Baptists into accepting Black Americans.”

Baptist missions representatives continued for years to warn that Baptists’ racial discrimination was, in the words of one missionary, “a constant threat to every American who works abroad.” But more than a decade after the 1954 decision, SBC missionaries were still using the pressures of the mission field to chide Southern Baptists into accepting Black Americans.

In what was becoming a common refrain, the 1965 Christian Life Commission’s annual report included calls for Southern Baptists to reject racism for the sake of their white co-laborers. The report declared the “racial crisis” was the most serious and fundamental challenge for the “Southern Baptist witness for Jesus Christ.”

“Our foreign missionaries have joined,” the report continued, “in the most moving and poignant pleas for Southern Baptists to reject racism and rise above racial prejudice and by so doing to unchain their hands to do their tasks for Christ among all the peoples of the world.”

By and large, Southern Baptists in the 1950s and early 1960s refused to grapple with the material realities of American segregation and racism. Because racism was a “spiritual issue,” Baptists kept the effects of racism in the spiritual realm, locating racism on the plane of individual animus and “racial pride.”

Of course, ethical language was deployed. Terms like “sin” and “partiality” and appeals to Galatians’ maxim, “neither Jew nor Greek,” could be found in convention sermons and missionary dispatches.

But the public face of the SBC, the twin concerns of democratic ideals and evangelistic fervor, and an awareness of U.S. foreign relations were front of mind for many in Nashville and abroad. Many saw the legal end to segregation as both a challenge to Baptist identity and an opportunity to bolster Southern Baptists’ reputation at home and abroad.

Many saw the legal end to segregation as both a challenge to Baptist identity and an opportunity to bolster Southern Baptists’ reputation at home and abroad.

Southern Baptists assented to Brown and encouraged gradual interracial harmony as a defense to any who questioned the denomination’s democratic or evangelistic bona fides.

Derrick Bell’s theory of interest convergence helps explain why Southern Baptists changed their minds when they did. Bell’s thesis also helps explain the limits of Southern Baptists’ commitment to racial equality across the 20th and into the 21st century. Bell argues the obverse principle of interest convergence is simply that when the interests of Black Americans and white Americans diverge — whether due to political, social or other factors — racial equality stagnates or even recedes in racial backlash. (Ironically, racial backlash within the SBC has included vitriolic campaigns denying the academic merits of Critical Race Theory for addressing the persistence of racialized violence and inequity in our country.)

The racial tenor of the SBC, particularly over the last half decade, ought to lead us to question whether the SBC believes committing to racial justice is in its best interest. We have seen an exodus of prominent Black pastors from the SBC. There has been lackluster moral reflection on the legacy of slavery at the SBC’s flagship seminary. We’ve seen the departure of Russell Moore from the ERLC and the SBC. We’ve watched the increasing alignment of Southern Baptists with a radicalized Republican base. We have heard the racial paternalism of the denomination’s loudest theological voice. We have seen the SBC prize narrow Bible interpretation on women’s leadership over cultural accommodation for nonwhite congregations.

Derrick Bell’s work helps us uncover the somber reality that, historically speaking, moves toward equality have hinged on the intersection of Black lives with the political, social or economic interests of white Americans. This was true of America in the 1950s and ’60s. It was true of the Southern Baptist Convention then. It remains true, it seems, today.

Jacob Randolph serves as assistant professor of the history of Christianity at Saint Paul School of Theology in Oklahoma City. He is a Ph.D. graduate of Baylor University.