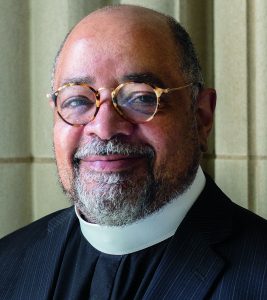

Leonard Hamlin Sr. serves as canon missioner and minister of equity and inclusion at the Washington National Cathedral. A Black Baptist pastor, Canon Hamlin oversees the Cathedral’s outreach and social justice work. Given the symbolic importance of its role as “the Nation’s church,” what the cathedral does matters in our nation’s religious and civic life.

The cathedral seems to float majestically above the city, but it is more than a Gothic monument; it’s also a community of believers seeking to make a difference in the world. In 2021, Canon Hamlin told PBS, “The Washington National Cathedral sits on St. Alban’s Hill, but scripturally sometimes the real work is not on the hill, it’s in the valley.”

I am grateful to Canon Hamlin for his commitment to that real work and for his willingness to talk with me about race, justice, politics and the church.

Greg Garrett: In 2018, you came to the cathedral after some years as pastor of the historic Macedonia Baptist Church in Arlington, Va. I wanted to ask you about that move. Our sister Kelly Brown Douglas has said for many years she did not feel welcome in the cathedral. Its longtime reputation was that it was unfriendly to people of color. Did you have that feeling about the cathedral yourself? What impelled you to accept the call to serve there? What were your hopes and fears about taking up a position as the cathedral’s point person on racial reconciliation?

Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Leonard Hamlin Sr.: Like many others, my impression of the cathedral was primarily based on what I had heard and on very limited experience. My impressions were shaped more by those I had an opportunity to meet than by what I had heard. Still, it was a great wrestle to accept the call to serve at the cathedral, as I had been pastoring for 22 years.

To come and serve in a space that seeks to be a House of Prayer for All and the Nation’s Church, those must be more than claims but also modeled and lived out. As a Baptist rooted in Black church tradition and theology and an African American male, I thought serving at the cathedral would not only offer a visible witness of working together but also encourage others that diversity does not weaken us but strengthens us.

I have hope and faith in what we have been created to be and in what we can be as we walk with God. I would describe my discomfort more as a deep concern than a fear.

In these moments, I am concerned about the human proclivity to reach for the familiar, to become committed to the mindset that declares we have always done it this way, to fail to walk by faith. While there are numerous ways to consider this tension, I remember the words of the writer of the letter to Hebrews, “But without faith it is impossible to please him. For he that cometh to God must believe that he is, and that he is a rewarder of those who diligently seek him,” and the words of the Prophet Micah, “He hath shown thee, O man, what is good: and what doth the Lord require of thee but to do justly and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?”

GG: Jemar Tisby recently lamented that so many white American Christians don’t know the deep resources and history of the Black church. Black theology and my own engagement with the Black church have helped me to a deeper vision of what Christian faith and practice means, and I know they could for others like me. Could you reflect on the gifts of the Black church for the white church? What wisdom does the Black church have around the 2024 election?

LH: We all bring a unique witness of life and unique perspective that helps us see more and strengthens our understanding. The Black church brings a witness that has been shaped by faith and experience, a long history of faith that has encouraged a critique of culture and society seeking to liberate the disinherited, disallowed and disavowed.

“There is a spiritual (and in many cases, literal) battle for the lives of the poor, the weak, the marginalized, for all those who are hurting to be treated justly.”

The 2024 election presents a unique season for a “voice crying out in the wilderness.” There is a spiritual (and in many cases, literal) battle for the lives of the poor, the weak, the marginalized, for all those who are hurting to be treated justly.

Dr. King said, “The church must be reminded that it is not the master or the servant of the state, but rather the conscience of the state. It must be the guide and the critic of the state, and never its tool.”

I believe the Black church continues to strive to serve as that conscience. The writer to the church in Corinth reminds us that the church must seek to strike the right note for these moments of challenge when they write, “For if the trumpet give an uncertain sound, who shall prepare himself to the battle?”

The Now and Forever Windows at the National Cathedral

GG: Last September, the Now and Forever windows by the eminent Black artist Kerry James Marshall were dedicated in the nave of the cathedral. They replaced the Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee windows donated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in the 1950s. I think of this as a powerful example of how an important American institution examined and repented of its past. Could you talk a little about this process and maybe what America could learn from this decision the cathedral made?

LH: Understandings are not always immediate. It often takes time to challenge conclusions that are incorrect or incomplete. The windows were placed in the cathedral when there was an acceptance and fostering of the Lost Cause myth. The images in the windows — most pointedly the Confederate battle flag — were sending messages inconsistent with the cathedral’s commitment to Christian faith and understanding. They divided the community rather than contributing to the building of community.

After the senseless murder of nine people at the Mother Immanuel Church in South Carolina, the dean at the time called for the removal of the windows. Greater understanding and the building of community does not come on the wings of ease. The process did not occur without conversations, debates and sharing of thoughts that led to greater understanding of the historical and theological messages being sent through the art and imagery. Humanity is shaped by the stories we tell and the values we share. The decision to tell a story of faith and history as honestly as possible is often challenging in the present moment but will strengthen us in future moments.

GG: The National Cathedral is indeed sometimes thought of as the Nation’s Church, the place where we pray after the inauguration of a president or lament national tragedies. Because of those very public moments, it has an outsize influence on the American church and on American culture. What are some of the programs you and the cathedral are working on now that you are excited about? What kind of wisdom can the cathedral offer into the tumult of this election year?

LH: In these inevitable moments of challenge and question, the cathedral embraces the opportunity to occupy that space between the civic and the sacred. It is in that space we gather seeking unity, common ground, the sharing of vision and the joy and blessing of fellowship.

Inside Washington National Cathedral

The cathedral’s strategic plan affirms our desire to “bring people together to engage in the work of reconciliation, promote interfaith engagement and support the efforts of the wider church to discern a vision for Christianity in the 21st century,” all through the ongoing work of the cathedral in worship, welcoming, programming and service.

The Now and Forever Windows presented the Cathedral with an increased opportunity to encourage the living out of the great claims we make as believers. We are looking forward to hosting the inaugural “Sacred Spaces: Racial Justice and Spirituality in Action” leadership program at the cathedral’s Virginia Mae Center. While there will be such convening and gathering moments during 2024, we are also prepared to respond to the “expected unexpected” activities required by our role as national church.

As we continue to walk by faith through this season and generational moment, I join with many others who continue to declare that “another world is possible.” In 1956, Dr. King said, “But the end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the beloved community. It is this type of spirit and this type of love that can transform opposers into friends. It is this type of understanding goodwill that will transform the deep gloom of the old age into the exuberant gladness of the new age. It is this love which will bring about miracles in the hearts of men.”

These words were spoken years ago but ring truth today and I believe miracles are still possible.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles in this series:

Politics, Faith and Mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby