Mainline Christians should not let themselves off the hook for enabling the ideology of Christian nationalism that currently threatens American democracy, author and journalist Brian Kaylor says.

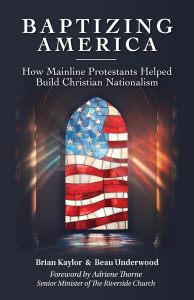

While white evangelicals get most of the blame, Mainline and other non-evangelical Christians must acknowledge their part in fostering the political ideology that seeks to merge Christian and American identities, said Kaylor, co-author of Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism.

This is a book that tells an often overlooked side of the story.

Brian Kaylor

“We have to flip the focus and look at the deep, long history of Christian nationalism within what is known as progressive congregations and denominations. But it can be uncomfortable to realize we are part of the problem,” said Kaylor, a Baptist minister and editor of Word&Way, a Baptist publication based in Missouri.

“For anyone who grew up in a white church in the U.S., Christian nationalism is just in the air that we breathe,” he explained. “We all need to do the work to detox, to separate the wheat and chaff from what’s gospel and what’s American. But it’s easier and more comforting to look at the extreme and dangerous examples of Christian nationalism today and to say, ‘Oh, we are not like those people over there.’”

Beau Underwood

In Baptizing America, Kaylor and co-author Beau Underwood expose the role Mainline churches and clergy played in helping establish pervasive customs and practices designed to fuse the institutions of nation and Christianity.

Among those traditions are American Baptist Churches USA, the Disciples of Christ, the Episcopal Church, the United Methodist Church, the United Church of Christ, the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Presbyterian Church (USA).

“Mainline Protestant denominations have played an outsized role in America’s history, given that most of the nation’s founders were members of what we now refer to as Mainline Protestant churches,” the authors write, adding that more than half of American adults belonged to one of those groups until the 1960s.

Today, “Mainline” is frequently used to describe similarly minded Protestant traditions that may also be labeled as “non-evangelical” in modern polling. “Together, Mainline Protestants still represent a significant religious tradition in the U.S., even if their glory days of cultural dominance have passed,” the authors note.

Those groups made strides in promoting the merger of faith and government through the mid-20th century when Christian nationalism was described in different terms, the book claims. “Phrases like ‘civil religion,’ ‘American exceptionalism,’ ‘religious nationalism,’ and others contain elements of what is now labeled as Christian nationalism.”

Baptizing America describes the post-World-War-II era as a “golden age for Christian nationalism,” a time when the National Day of Prayer (1952) and the National Prayer Breakfast (1953) were launched, and when “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance (1954).

Baptizing America describes the post-World-War-II era as a “golden age for Christian nationalism,” a time when the National Day of Prayer (1952) and the National Prayer Breakfast (1953) were launched, and when “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance (1954).

President Dwight Eisenhower presided over a 1954 ceremony unveiling a new 8-cent stamp featuring an image of the Statue of Liberty and the words “In God We Trust.” Disciples of Christ minister Roy Ross, leader of the National Council of Churches, offered the invocation, according to the book.

“Oh God, imbue with the spirit of wisdom those to whom in thy name we entrust the authority of government,” he prayed. “Grant that this new instrument (the stamp) which we dedicate this day may present an effective message of faith and freedom throughout the whole wide world.”

A patriotic prayer proposed for New York school children in 1951 became a rallying cry for Mainline clergy concerned about the character of American youth. Among them was Norman Vincent Peale of Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan. “Every patriotic and thoughtful citizen of all faiths should enthusiastically endorse the proposal,” he said. “This country cannot endure if we cannot at least mention God in the schools.”

Kaylor and Underwood note the irony of that statement coming from a high-profile Mainline minister: “If it is now considered Christian nationalism to advocate for official prayers in public schools, then it was also Christian nationalism when Presbyterian, Episcopal, Lutheran and Methodist clergy helped get such prayers into schools in the first place.”

But the desire for faith-infused government did not end with the decline of Mainline Christianity. According to Kaylor and Underwood, it was on full display in a Jan. 6, 2022, ceremony memorializing victims of the 2021 insurrection. The invocation was delivered by Michael Curry, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in America.

“’We need your help, Lord, now, to be the democracy you would have us to be, to be the nation you would have us to be — one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all,’ he prayed.”

The prayer was followed by a singing of “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” and a moment of silence led by Democratic Sen. Nancy Pelosi.

“If that service had been exactly the same but we switched out the leaders with conservative evangelical figures, it would have quickly been criticized by many as Christian nationalism,” the authors say. “Imagine Paula White-Cain saying the prayer, Sean Feucht singing those hymns, and Speaker Mike Johnson introducing the moment of silence.”

“If there is opposition to removing anything other than a Bible or a cross from the church, then it is an idol.”

In an interview with BNG, Kaylor said most Christians will spot the signs of Christian nationalism in their own churches if they are intentional about looking: “For generations, Christian nationalism has just been so naturally embedded in American Christianity that to have a flag in the sanctuary, to sing patriotic hymns on the Fourth of July during church services, just seems the way faith is supposed to be. It makes it harder to realize what is cultural and what is actually coming from the Bible.”

Individuals and congregations wanting to untangle from the ideology of Christian nationalism can begin by delving into the history of their own communities, Kaylor said. “We suggest looking at your own story, your own church, your own denomination. How has your church or denomination engaged in the public square? Do you sing patriotic hymns? Is there a flag in the sanctuary?”

Pastors can help by promoting a global vision of the church, he said. “See and value Christians on the other side of the border to see how they read the Bible and worship in ways that are radically different from those of us in the empire.”

To determine if Christian nationalism has attained an idolatrous status in a church, try to remove the U.S. flag from the sanctuary, he suggested. “If there is opposition to removing anything other than a Bible or a cross from the church, then it is an idol.”

But there remains a significant difference between having the trappings of Christian nationalism in a church versus storming government buildings in the name of Christ, Kaylor said. “In a way, there’s a little bit of Christian nationalism in us all, but that doesn’t mean we are Christian nationalists.”