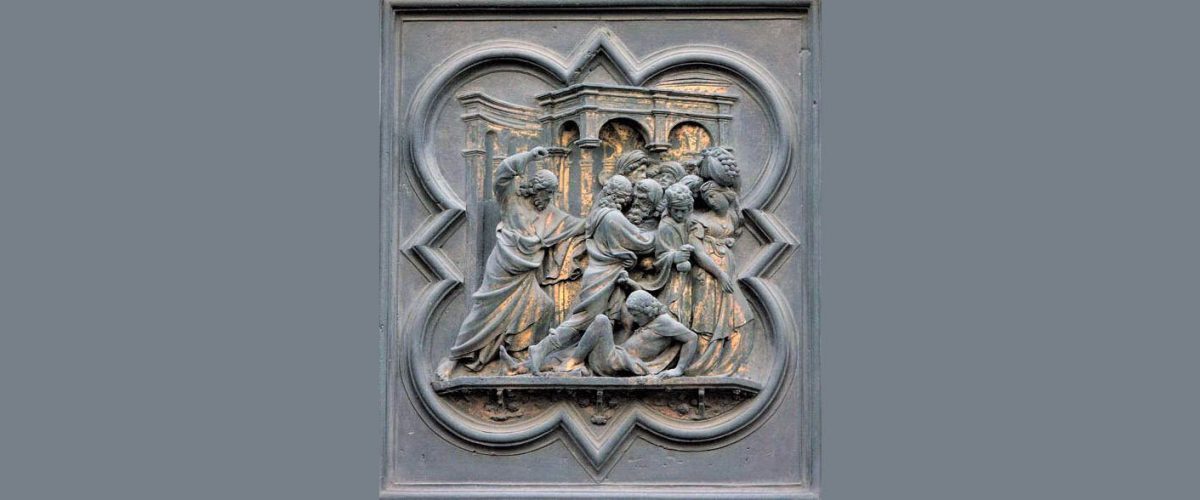

This coming Holy Week, Christians remember Jesus’ “cleansing of the temple” in Jerusalem. He was setting his opposition to the temple priesthood and their collusion with Rome to sustain an unjust social order that oppressed the weak and poor. As he drove the money changers out of the temple, he invoked the words of Jeremiah: “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples, but you have made it a den of thieves.”

God had said through Jeremiah centuries before, “Amend your ways, and let me dwell with you.” It was a poignant plea. True prophets always have a tear in their eye.

Stephen Shoemaker

Then God spoke what such an amendment of life and faith would look like: “If you truly act justly with one another, if you do not oppress the alien (immigrant), the orphan and the widow, if you do not shed innocent blood … then I will dwell with you in this place.”

Then this last searing question, “Has this house which has been called by my name become a den of robbers?!” No wonder the king had him lowered down into a deep cistern to shut him up.

It has been the shadow side of the church through the centuries: When the church and state are in bed together the most vulnerable of the society suffer and the “enemies” of the church — heretics, infidels, unruly women, Jews and more — have suffered persecution at the hands of the sword of the state. We need the words of Jeremiah and Jesus today as white Christian nationalists militate against the separation of church and state and want the church of Jesus to rule, not serve. Our temples need cleansing. They need to be accountable to Jesus.

But what of our forgiveness of church? Do we need to do this, for our sake as well as the sake of the church?

During the Third Reich, when German Christians fell under the thrall of Hitler, the Confessing Church was birthed to say, “Only Christ is Lord.” Some lived together in community for a while. Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote about this in his book Life Together. In it he pondered the meaning of true community and challenged those pastors and zealous church members whose criticism of their church community had robbed them of gratitude for the church in which they had been placed.

“In my pursuit of the perfect church, I almost missed the one I had.”

The problem, he said, was the “wish-dream” pastors and zealous leaders of the church had for their church. When the church does not become what they wish it to be, they become accusers of the church, they grow critical and withdraw affection. Such “wish-dreams,” he wrote, should fall shattered to the ground like toppled idols, and we should thank God for their shattering. Only then can we work together in gratitude for its renewal.

Carlyle Marney once said, “In my pursuit of the perfect church, I almost missed the one I had.”

But what about our forgiveness of church, the institutional church, the church we belong to, or used to belong to? A friend in my former church had been a devoted Roman Catholic and had grown disillusioned with his church. He told me of a spiritual turning point in his life. He went on a Catholic retreat led by a priest. In a private session with him he poured out his anger at the church, his disillusionment and disappointments. After listening quietly, the priest said, “Dennis, I think you need to forgive the church.” Dennis did, and the stone in his heart dissolved, and he became a vital member of my church.

Can one forgive an institution that has wandered from the way of Jesus? Do we need to forgive a church that has hurt us, even damaged us? Such forgiveness does not mean minimizing the harm done or refusing to call it into account. But for our own good? Can we admit its humanity and forgive the church the way we need to forgive other persons and ourselves? Can this loosen our despair?

The story of the church through the centuries has been a play of shadow and light, a confounding mixture of faith and unfaith — like Peter, one moment a rock of faith, the next a series of shabby denials. Sometimes it has been Christ’s face, the next Christ’s betrayer, a mockery of his name and face. But God in God’s steadfast love has made good on the promise that the Living Christ would be with us always, and this has resulted in the true church being present somewhere in all places and in all times.

The renewal and reformation of the church has happened in such unlikely places as monasteries and splintered London streets, in brush arbors revivals and maybe in what looks like dying churches today.

Stephen Shoemaker serves as pastor of Grace Baptist Church in Statesville, N.C. He served previously as pastor of Myers Park Baptist in Charlotte, N.C.; Broadway Baptist in Fort Worth, Texas; and Crescent Hill Baptist in Louisville, Ky.