Maybe you’ve seen the social media meme. Hundreds of old-timey cars are parked willy-nilly on the lawn of an old country church. The faithful are streaming into the sanctuary. “Back in the day,” the caption reads, “everyone went to church and knew they needed God. … I wish it was still this way and believe it can be!!!”

There were a lot more people in American churches 70 years ago. The first congressional prayer breakfast took place in 1953. Republicans and Democrats didn’t always have the same political agenda, but both parties wanted to identify with church folk.

Alan Bean

“In God we Trust” became America’s official motto in 1956, a response to the “godless communism” of the Soviet Union.

Some sociologists called it “civil religion,” others preferred the phrase “ceremonial Deism.” Whatever you called it, Mainline Protestants, evangelicals and Catholics embraced the same religious tenets.

People believed in a God who answers prayers.

Virtues like hard work, honesty and fair play were encouraged from the pulpit.

There was a heaven for good people and a hell for the baddies.

America was a nation favored by God.

So long as people agreed to this rough-and-ready consensus, religious tolerance was celebrated.

“So long as people agreed to this rough-and-ready consensus, religious tolerance was celebrated.”

While it is a gross exaggeration to suggest that “everyone went to church” back in 1954, or that everyone “knew they needed God,” churches were packed, new churches were springing up like daisies, and Hollywood moguls were forced to tailor their product to religious sensibilities.

People went to church because that’s what normal people did. They believed in God for much the same reason. Billy Graham didn’t argue with skeptics, he just said what everyone knew to be true.

No one decides for or against a religious consensus; you take it in with your mother’s milk.

Those days are gone

Those days are gone, dead and buried. A quarter of Americans may dream of turning the clock back to 1954, but another quarter celebrates the progress America has made since those dark days. At least half the population doesn’t give the matter a great deal of thought. Our growing partisan divide is a fight, largely among white people, over the virtues and vices of the old religious consensus.

Before the armies of Nebuchadnezzar arrived, Judah enjoyed a religious consensus of its own. The nation, particularly Jerusalem, and most particularly Solomon’s temple, were considered impregnable. God had promised the great king David it would be so. The 10 northern tribes of Israel had fallen to the Assyrian empire in 722. Judah had been spared because a descendent of David sat on the throne.

“Our growing partisan divide is a fight, largely among white people, over the virtues and vices of the old religious consensus.”

But the religious consensus crumbled like the walls of Jerusalem, and all the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put it together again.

Not everyone was ready to throw in the towel. Judah was being punished for her sins; but the steadfast love of Judah’s God would eventually turn the tide.

Facts on the ground suggested otherwise:

- The fighting men of Judah were either dead or sold into slavery.

- Jerusalem was a heap of ruin.

- Solomon’s temple, the very dwelling place of God, had been ground to rubble.

- Princes, priests and prophets had either been slaughtered like dogs or dragged off to a strange land.

- As famine raged, nursing babies and old widows were slowly dying of hunger.

- Women throughout the length and breadth of Judah were being savagely raped.

The old religious consensus was dead and buried. There was nothing for it now but to lay out the dreadful facts, read them and weep.

Lamentations

In the book of Lamentations, both groups have their say. Of the seven 22-verse units in Lamentations, only one is hopeful, and it is sandwiched by despair.

Every year, Jewish congregations commemorate Tisha b’Av, an annual fast day that remembers the most appalling events of Jewish history. The destruction of Jerusalem and the Babylonian exile form the heart of the story. In the course of a 25-hour fast, the faithful are expected to forego all things pleasurable, the reading of Scripture included. An exception is made for Lamentations. The text must be read in its entirety during Tisha b’Av.

“Jews make room for lament; Christians, for the most part, do not.”

Jews make room for lament; Christians, for the most part, do not. Some Christians gather on Holy Saturday, the day between Good Friday and Easter. On Holy Saturday, Christians are called to mourn and lament for God lies dead.

The evangelical Christianity that nurtured my faith didn’t do Holy Saturday. We don’t even display the crucified Christ in our churches. Our crosses are empty. The glory of Easter morning sucks all the horror out of Golgotha.

Until this week, I had never read the entire five chapters of Lamentations through in a single sitting. To be honest, the text frightened me. The poet’s descriptions of human suffering take me to dark places I’d rather not visit. But I found the courage to read the whole thing through. And then I read it again. And again. It wouldn’t let me go.

I couldn’t help noticing that the poet of Lamentations makes reference to “daughter Jerusalem,” “daughter Judah,” “daughter Zion,” and, in a couple of places, “virgin daughter Zion.” Judah is repeatedly compared to a young girl, innocent and helpless.

Then I noticed how much the plight of girls, elderly widows and the starving mothers of infant children dominate the text. If I hadn’t been reading Bessel Van Der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score, a book that addresses the long-term impact of child abuse, I might have missed this fact. The poet of Lamentations flirts with a disturbing question: Has Yahweh become an abusive father?

The same question must be asked of the Christian church.

Baptist midwives

Nancy and I had just watched Midwives of a Movement, a documentary produced for Baptist Women in Ministry. In the late 1970s, women started showing up at Southern Baptist seminaries. As little girls growing up in GAs, these women had been asked if God was calling them into “full-time Christian ministry.” They answered in the affirmative.

They weren’t just at seminary to learn how to be a pastor’s wife or a missionary. They wanted to preach. They wanted to serve as ordained clergy. They were saying yes to God. At Southern Seminary in Louisville, Ky., these young women received encouragement from an outspoken cadre of progressive professors. That’s how Baptist Women in Ministry was born.

“The real story reads more like the text of Lamentations.”

My wife, Nancy, was one of those students. I wish I could tell you these “midwives” sparked a movement that transformed Baptist life, but the real story reads more like the text of Lamentations. Within the Southern Baptist Convention, the women in ministry movement sparked a brutal internecine power struggle. Like ancient Israel, the SBC split into two groups, one big and brimming with bluster; the other small and bewildered.

A brutal logic was at work. If God calls women to pastoral leadership, a church that rejects women in ministry is guilty of grievous sin. And if we have oppressed our women, what of the endorsement of slavery and Jim Crow segregation? And if we have sinned against Black people, maybe we need to reevaluate our attitude toward LGBTQ folk.

When the excluded are allowed a voice, the dominoes begin to fall. To keep that from happening, SBC leaders asserted it was the “Spirit of Jezebel” not the calling of God, that made these women want to preach.

Seeking a new vision

How do we respond to this tidal wave of rejection?

If we take our cue from the poet of Lamentations, we will just lay out the facts and weep. And then we wait for God to speak a new word. There is no certainty here. What if there is nothing but silence?

Once a religious consensus is broken, it cannot be cobbled back together. If a grain of wheat is to bear much fruit, Jesus told us, it must fall into the earth and die (John 12:24). The same principle applies to hope.

“A new, enlarged vision of God cannot live among us until the old, impoverished vision dies.”

A new, enlarged vision of God cannot live among us until the old, impoverished vision dies. If death doesn’t feel final, it isn’t really death. Consider the final words of Lamentations:

Restore us to yourself, O Lord, that we may be restored;

renew our days as of old —

unless you have utterly rejected us

and are angry with us beyond measure.

God never renews our days “as of old.” God is always doing a new thing.

In ancient Israel, women always took the lead in times of joy and sorrow. Women did the emotional work of the community. When God fell silent, women led the communal lament. It’s a language they have learned through painful experience.

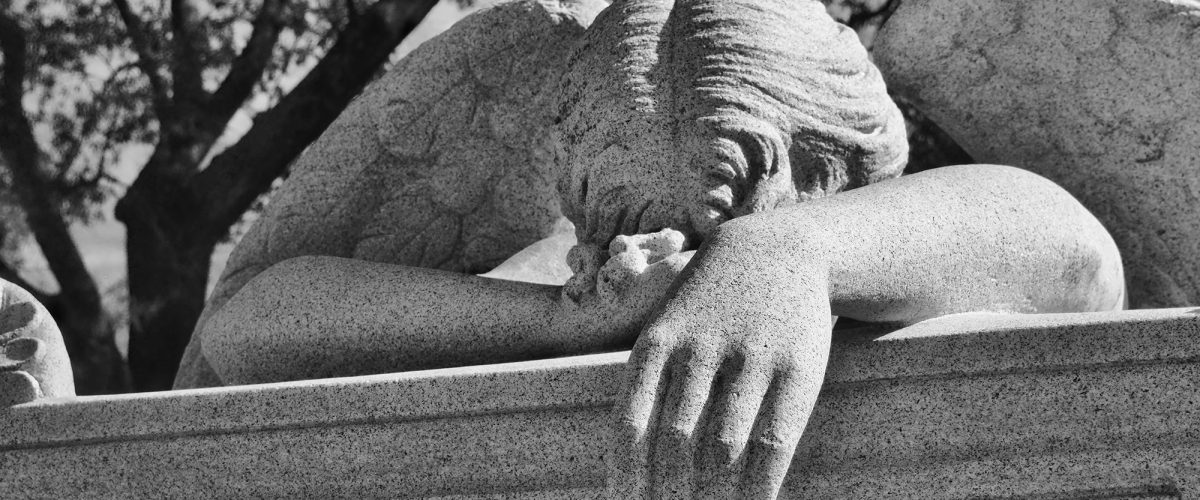

For decades now, we have been living in Holy Saturday, the time between death and new life. God lies dead. Hope is exhausted. It is both appropriate and necessary that our women lead the lament. In these dying days of Lent, let us weep with daughter Zion.

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas.

Related articles:

Beauty from ashes: How catastrophe shaped the Bible | Opinion by Alan Bean

BWIM’s 40th anniversary gathering features new documentary