“There is a difference between being secular and being ANTI-CHRISTIAN,” wrote Shane Pruitt, National Next Gen director for the Southern Baptist Convention’s North American Mission Board. The anti-Christian culprit he had in mind was not one of the many examples of male church leaders in Southern Baptist churches who abuse Christ by abusing “the least of these.” Instead, the mocker, according to Pruitt, is none other than Taylor Swift.

“I used to listen to Taylor, HOWEVER, I think now it’s time to reconsider,” Pruitt lamented. “As Christians, who are filled with the Spirit should we be entertained by, sing with, and expose our kids to lyrics that aren’t just different than what you believe, but are actually mocking what you believe?”

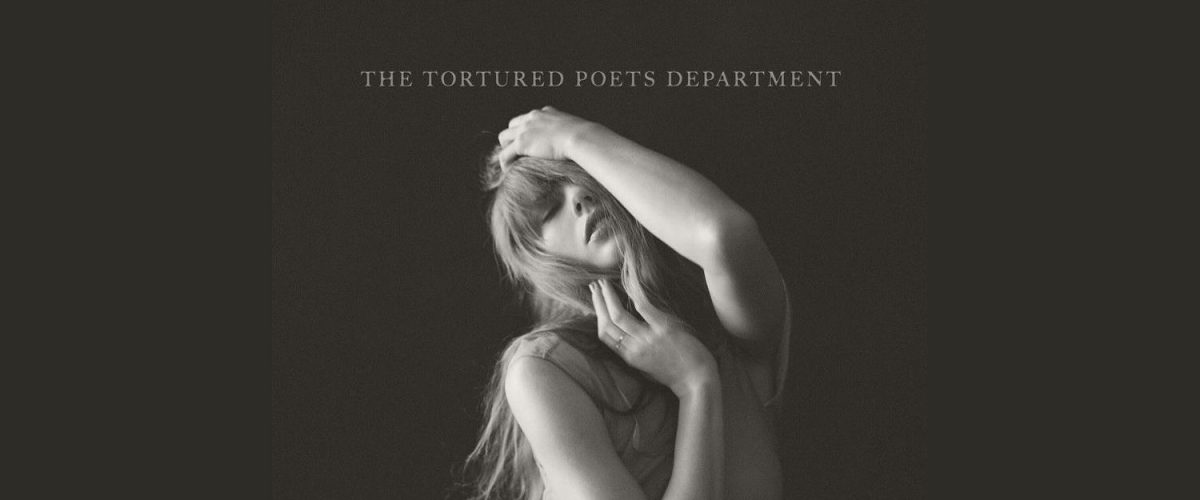

Pruitt is hardly alone in his criticism of Swift in the wake of her most recent album, The Tortured Poets Department. Christian nationalist worship leader Sean Feucht fussed: “Almost half the songs on Taylor Swift’s new album contain explicit lyrics (E), make fun of Christians and straight up blaspheme God. Is this the music you want your kids listening to?”

Pruitt is hardly alone in his criticism of Swift in the wake of her most recent album, The Tortured Poets Department. Christian nationalist worship leader Sean Feucht fussed: “Almost half the songs on Taylor Swift’s new album contain explicit lyrics (E), make fun of Christians and straight up blaspheme God. Is this the music you want your kids listening to?”

In addition to complaining about Swift, Feucht is also cashing in on her popularity by selling a “Jesus Christ: The Eras Tour” T-shirt on his website that looks identical to Swift’s Eras Tour T-shirt.

The popular Christian entertainment review website Movieguide jumped on the bandwagon as well, accusing Swift of mocking the power of prayer, denying God can change people, denying Christian sexual ethics, bashing Christians who evangelize, and practicing occult worship. With much of their review focusing on sexuality, they conclude: “The fact that one of the most popular and famous celebrities of her generation cannot find happiness reveals that living in the world leads to death while living for Christ and under his teachings leads to life. Unfortunately, Swift has chosen the path toward death and is reaping the fruits of her labor.”

Continuing the ‘Holy war’

This isn’t the first time this year conservatives have been miffed at Swift. In January, Rolling Stone reported some of Donald Trump’s campaign staff had declared preemptive “holy war” against her out of fear she might endorse Joe Biden in the upcoming election. Because Swift is dating Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce, conservative conspiracy theorists suggested perhaps the NFL season was rigged to help the Chiefs win in order to give Swift more air time during Chiefs games with the goal of promoting Biden.

Four months later, Swift still has not publicly endorsed Biden for the 2024 election. But if the conservatives from January were serious about waging a pre-emptive holy war against Swift, then perhaps the current panic is an ongoing part of their war for power.

In any case, the story here is not about analyzing Swift’s lyrics to figure out if she is an occult worshiper who hates Christians. And the bigger story is not even about Christian nationalists waging a holy war against Swift during a presidential election.

“Conservative Christians are treating Swift the same way they’ve been treating female CCM pop stars since the 1970s.”

What’s really going on here is that conservative Christians are treating Swift the same way they’ve been treating female CCM pop stars since the 1970s.

Saving the kids and the nation from sex, drugs and hell

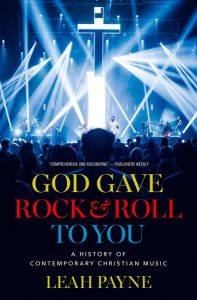

In her book God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music, historian Leah Payne shares how the Contemporary Christian Music movement grew amidst the fear that “hippies” were a “threat to American society.”

Parents were especially concerned because, as David Wilkerson warned in 1967, the hippies were sending young people “straight to hell.”

Leah Payne

Additionally, the growing obsession with Christian Zionism, the rapture and the end times during the 1970s made these concerns even more urgent.

In order to save their kids and the nation from hell and the Tribulation, evangelical parents reluctantly began to give in to the music of the Jesus Movement and eventually the CCM movement in hopes their kids and the nation would submit to their view of abstinence from sex and drugs.

“If everything went according to plan, young men would be faithful providers and leaders of their household. Young women would be nurturing keepers of the home — and under no circumstances would they be feminists,” Payne explains. “Together, they would guarantee a preferable, prosperous future for the nation.”

CCM’s Barbie and Ken

While evangelicals had classes, books and even horror movies to promote submission to their theology, Payne suggests that “concrete examples of young people who embodied those evangelical norms were even better.”

As Christian bookstores sold the theology and ethics of James Dobson and Bill Gothard, promoters of CCM began creating songs and albums to champion their ideas.

“CCM pop stars, therefore, came to be highly valued assets for evangelical media makers and consumers looking to protect the young, promote the virtues of a God-honoring life, and celebrate the prosperity that accompanied the evangelical lifestyle,” Payne recalls.

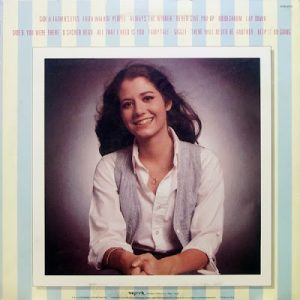

Thus, Payne details how Amy Grant became “the evangelical Barbie of CCM,” while Michael W. Smith was “the complementary Ken doll.”

Being attractive without being too attractive

As CCM’s Barbie, Grant needed to embody “the unattainable ideal of beauty and virtue of her generation.” This meant many young men would need to find her desirable.

Payne explains: “To sell records to evangelical consumers, it was important to visibly embody what godly living could do for a believer, which — for a woman — included being seen as marriage material. The ideal CCM star, therefore, would have a chaste, disciplined body that conformed to white middle-class beauty standards.”

“If one was too attractive, according to contemporary standards, one could be accused of enticing men with sexual worldliness.”

This put Grant in a precarious position, however, because as a woman who signed her first record deal at age 17, she had the responsibility of being attractive enough to make evangelical men want to desire her or another woman just like her, but without turning them on too much. “If one was too attractive, according to contemporary standards, one could be accused of enticing men with sexual worldliness, a violation of Holiness standards of modesty and purity,” Payne explains.

Powerful white evangelical men analyzing women’s sexuality

While many lay evangelicals lived their lives assuming they were simply submitting to the Bible, the reality was the gatekeepers of evangelical theology were corporate executives who owned the bookstores and record companies that taught evangelicals their theology. And as Payne notes, “The historic whiteness of the Christian Booksellers Association, and the FBI’s campaign against Black-owned bookstores in the 1970s, ensured that most Christian bookstore owners were white.”

Thus, these white men were in charge of determining when Grant and other female CCM artists crossed the line from being sexually desirable enough to marry to being supposedly too sexually enticing to resist. So Payne denotes, “As Grant cranked out hit after hit, her body and her body of work became the site for an ongoing conversation among evangelicals.”

In order to make sure female CCM artists didn’t cross the line, executives included a “moral clause” in their contracts that addressed everything from requirements for sexual abstinence to dress codes and dance standards.

Grant’s fall by embracing and discussing her own sexuality

Because CCM was born out of opposition to “the world,” the assumption for many years was that CCM artists had to sing exclusively Christian songs. But Grant didn’t agree with these rules.

“I always felt like I was trying to walk on one leg when I only sang gospel songs, when I played the part of the good girl, when I only sang my acceptable thoughts,” Grant confessed as her career continued to take off in the 1980s.

One of the first examples of powerful white men accusing Grant of pushing the boundaries was during her 1979 album My Father’s Eyes. Grant’s former youth pastor and producer, Brown Bannister, told the Washington Post people called it the “three-button controversy.”

One of the first examples of powerful white men accusing Grant of pushing the boundaries was during her 1979 album My Father’s Eyes. Grant’s former youth pastor and producer, Brown Bannister, told the Washington Post people called it the “three-button controversy.”

Payne gives the details in her book: “When Grant’s album cover featured a V-neck shirt with the first three buttons unbuttoned, it scandalized vigilant observers. Grant’s album was banned by some bookstore owners who retained Holiness code sensibilities and believed even the suggestion of risqué outer garb indicated inner corruption.”

After almost a decade of having to limit her singing to what white male executives considered to be “acceptable thoughts,” Grant opened up to Rolling Stone about her sexuality. In addition to the article confirming her affirmation of sex as being legitimate only within heterosexual marriage, Payne says, “the interview also included stories about how Grant had sunbathed naked and enjoyed sex.”

“My hormones are on key as any other 24-year-old,” Grant said at the time. “I’m trying to look sexy to sell a record. But what is sexy? To me it’s never been taking my shirt off or having my tongue sticking out. I feel that a Christian young woman in the ’80s is very sexual.”

Evangelical men everywhere began flipping out, flooding Christianity Today with accusations of Grant “running wild.” Jimmy Swaggart called her “very fleshly” and “sensual.”

While Grant began her career with what Payne describes as “a picture of virginal innocence and wholesome beauty,” she was also “hardly a stay-at-home mother.” Instead, Payne says, “She was an industry powerhouse who financially supported not just her husband and children but her band, managers, promoters and record-label employees.”

When Grant and her husband, Gary Chapman, divorced in 1999, CCM fans described it as everything from confusing to infuriating.

CCM’s Pop Princesses

The 1990s world of pop music brought us the likes of Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Mariah Carey and Celine Dion. So 1990s CCM attempted to market its own set of ideal women.

Payne calls Rebecca St. James “the obvious heir to Amy Grant.” James was heavily involved in promoting the 1990s purity culture. She wrote the hit song “Wait for Me” in honor of Joshua Harris’ bestselling book, I Kissed Dating Goodbye.

Jaci Velasquez also promoted purity culture, telling Baptist Press, “I hope and pray that every single person will make this commitment.” But Focus on the Family’s Plugged In movie review site criticized her for her debut acting role in Chasing Papi due to wearing “skimpy outfits.” Velasquez also was under constant surveillance for her voice. In an interview with Billboard, she said, “Ever since I was a little girl, I’ve always had people in the studio tell me to watch myself so that I didn’t sound too sexy.” After her divorce in 2005, her career was basically over.

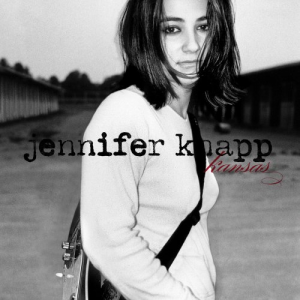

Jennifer Knapp converted to Christianity as an adult. So she didn’t share CCM’s obsession with purity culture. But she also wasn’t trusted. Payne recalls: “Knapp’s body was closely monitored for evidence that she crossed the carefully delineated boundaries of white evangelical sexual ethics. She was first introduced to bookstore moms through a compilation CD, but retailers worried that when evangelical caregivers saw the Kansas cover, which included the singer posing with a guitar strap resting between her breasts, customers would feel that the album was too sexy. Knapp’s powerful stage presence and proficiency with the guitar — a longstanding phallic symbol for male rockers — was also deemed too seductive for the overwhelmingly male Audio Adrenaline audiences.”

Jennifer Knapp converted to Christianity as an adult. So she didn’t share CCM’s obsession with purity culture. But she also wasn’t trusted. Payne recalls: “Knapp’s body was closely monitored for evidence that she crossed the carefully delineated boundaries of white evangelical sexual ethics. She was first introduced to bookstore moms through a compilation CD, but retailers worried that when evangelical caregivers saw the Kansas cover, which included the singer posing with a guitar strap resting between her breasts, customers would feel that the album was too sexy. Knapp’s powerful stage presence and proficiency with the guitar — a longstanding phallic symbol for male rockers — was also deemed too seductive for the overwhelmingly male Audio Adrenaline audiences.”

Knapp announced in 2010 that she had been in a relationship with another woman for eight years. But despite refusing to denounce Christianity, evangelicals no longer would have anything to do with her. She said, “Pretty much the whole Southeastern United States was out of the question after that.”

Jessica Simpson was the daughter of a Southern Baptist pastor from Texas named Joe Simpson who regularly talked about his daughter’s “large breasts and sex appeal.” As Payne details, “Simpson recalled that when she was just in seventh grade her breasts drew men’s attention when she sang special music, and she was scolded for eliciting lust from the congregation.” So Simpson said, “Anytime I sang (in church), I covered myself.”

When 13-year-old Nikki Leonti went on tour in 1998, Payne says, “According to Leonti … she was unprepared for how her teen body would be sexualized by the men around her.” Leonti said, “Married Christian men would call me ‘eye candy’ — I was 14 or 15 years old.” Because she grew up with no sex education, she didn’t understand how babies are conceived. So as a 17-year-old girl, she trusted her 21-year-old guitarist and became pregnant and was never successful again. Any time she tried to make a comeback, the only thing evangelical media outlets wanted to ask her about was her sex life.

White evangelical suburban moms and Taylor Swift

With an entire generation of evangelical girls growing up while looking up to and feeling let down by CCM’s Pop Princesses, they now were white evangelical suburban moms waiting in the carline for their own daughters. And along came Taylor Swift.

“The reign of virginal CCM pop starlets was eventually threatened, however, by a teenage singer from West Reading, Pa., named Taylor Swift,” Payne writes. “Swift was a pretty, petite blonde teenager who wore modest clothing and wrote chaste country songs with plenty of adolescent longing and Christian imagery.”

“The reign of virginal CCM pop starlets was eventually threatened, however, by a teenage singer from West Reading, Pa., named Taylor Swift,” Payne writes. “Swift was a pretty, petite blonde teenager who wore modest clothing and wrote chaste country songs with plenty of adolescent longing and Christian imagery.”

In an interview with Baptist News, Payne further explained, “Evangelical moms could listen to her in the minivan and not worry about the lyrics undermining any of their teachings (in contrast to her predecessors like Britney).”

Throughout her book, Payne tells how the evolution of CCM into stadium rock worship music during the 2000s led to an even lower representation of women leading worship than women had during the heyday of CCM. Much of this was due to patriarchal Reformed men like John Piper joining with the Passion movement, requiring spiritual leaders to be men and elevating worship music production to the status of spiritual leadership.

Forefront A&R representative Mark Nicholas agreed with Payne’s perspective. “I think the real end for a lot of pop CCM was Swift,” he said. “The same moms who brought their daughters to CCM concerts felt comfortable bringing them to a Taylor Swift show.”

Weird Barbie and the women who questioned their script

In the 2023 hit Barbie, Stereotypical Barbie begins experiencing thoughts, feelings and her body in ways those in charge say she isn’t supposed to. When she tells her fellow Barbies what she’s processing, one exclaims, “You’re malfunctioning!”

“You’re going to have to visit Weird Barbie,” suggests another.

Michael W. Smith and Amy Grant

Then a third explains that Weird Barbie was played with too hard in the real world and now is “fated to an eternity of making other Barbies perfect while falling more and more into disrepair herself.”

There’s a sense in which reading the stories of all the women in Payne’s work reminds me of Barbie questioning the script of the white male corporate executives as they grew into adulthood. As Payne told Baptist News, “The transition from virginal girlhood to the complexities of adult life and womanhood was often a rocky one for CCM stars.”

In the movie, the creator of Barbie says, “Humans make things up like patriarchy and Barbie just to deal with how uncomfortable it is.”

When CCM began in the 1970s, evangelicals were promoting men as patriarchs and women as Evangelical Barbies due to how uncomfortable they felt about hippies, hell and the end of the world.

That’s exactly why white male executives and bookstore owners turned Amy Grant into what Payne called “the evangelical Barbie of CCM.” Their bodies were analyzed and controlled to be desired but not too much. And then they were cast off as Weird Barbies when they dared to have unacceptable thoughts and feelings about their bodies and sexuality.

But what if the white male executives of the CCM industry are not the ones who define their reality?

Barbie says, “I want to be a part of the people that make meaning, not the thing that’s made. I want to do the imagining.”

What if these women have simply chosen not to be Evangelical Barbie anymore? What if they’ve chosen to become human? And what if they don’t need our permission?

Could we look back to see how far they’ve come?

The Tortured Poets

Just as Grant, Velasquez, Knapp, Simpson and Leonti came under the ire of white evangelical male executives for stepping outside of their boxes, so now is Taylor Swift.

The lyrics men are complaining about are when Swift says, “I just learned these people only raise you to cage you.” Or “God save the most judgmental creeps who say they want what’s best for me.”

(courtesy-of-@taylorswift-on-instagram)

That’s not an attack on Christianity, unless your Christianity excludes women standing up to the patriarchy just as many of CCM’s female artists have.

Payne agrees with this parallel. She told Baptist News Global: “I do wonder if the evangelical response to Swift now is better understood in the context of Grant, (Sandi) Patty, and other CCM stars who were held up as exemplars and then torn down when they didn’t conform to the strict expectations for life and godliness that came from those communities.”

Ultimately, I would take these patriarchal control tactics all the way back to the origins of CCM, where white men assumed there were two realities that had to remain separate.

As Barbie took off to the real world, the other Barbies called out, “Bon voyage to reality and good luck restoring the membrane that separates our world from theirs.”

In the case of Swift and CCM’s tortured former female poets, that’s what this is about. It’s about taking one another’s hands, closing our eyes and feeling.

Or as Swift put it, “What if the way you hold me is actually what’s holy?”

In that sense, what if Swift and the Weird Barbies of CCM have opened a portal to the real world? What if they are showing us how everyone’s thoughts, feelings and bodies are inextricably intertwined? What if they are showing us what it means to be human?

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

New history sees CCM as a ‘soundtrack’ for white evangelicalism | Analysis by Steve Rabey

Amy Grant will host a same-sex wedding, Franklin Graham objects, and where does that leave Michael W. Smith? | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Why are conservatives so afraid of Taylor Swift? | Analysis by Rick Pidcock