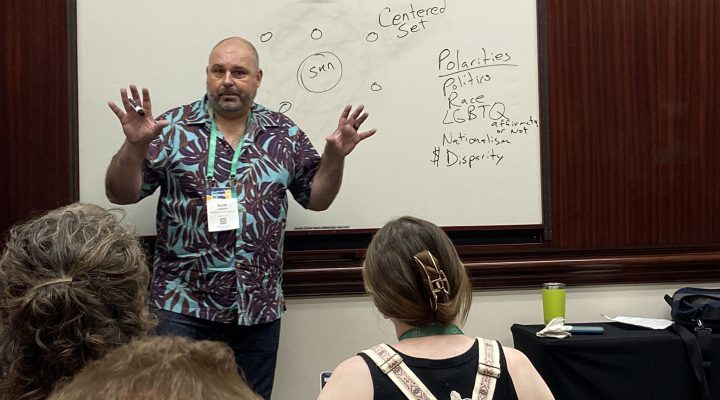

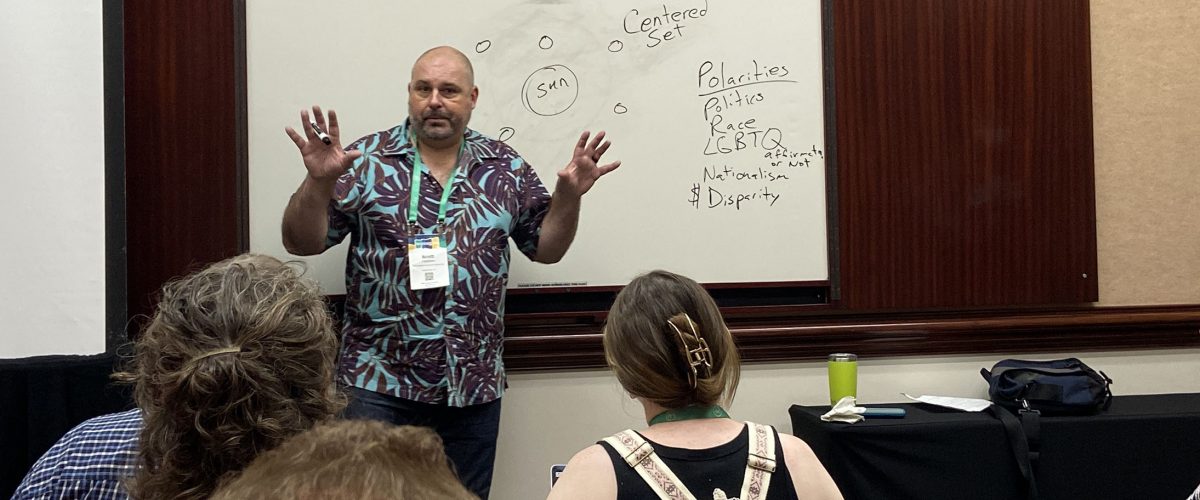

In order to find peace amidst polarity, consider two ways of raising cattle, California pastor Scott Capshaw told participants at the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s General Assembly in Greensboro, N.C., June 20.

Capshaw, pastor of First Baptist Church in Tahoe City, led a breakout session on “Creating Spaces of Peace in an Increasingly Polarized World.”

“I grew up in a fundamental space,” Capshaw said. “Then I deconstructed my faith in seminary and became progressive. … Later, in 2016, I began losing faith — not in Christ, but in the church.”

His struggle caused him to ask an existential question: “How do I say I am a Christian?”

Capshaw credited the Jesus Collective and its emphasis on “Jesus-centered Christianity” for helping him re-think faith and church.

To illustrate, he asked participants to consider two ways of raising cattle.

His grandparents’ farm in Western Tennessee included a fence to keep the cattle from wandering, he said, noting, “This is like a bounded set — the picture of most organized religion.”

A bounded set depends upon rules or beliefs that form a kind of fence to determine who is “in” and who is “out,” he said. “When we meet someone, we know what to say — the ‘dog-whistle’ phrases,” which elicit responses to indicate whether the other person is part of the group.

“No matter whether we’re fundamentalist or progressive, we know who is in and who is out.”

“No matter whether we’re fundamentalist or progressive, we know who is in and who is out,” he said.

Bounded-set norms heighten polarities that divide people and decrease the numbers of people who are in a church or group, he added. Asked to name current polarities, participants listed politics, race, affirmation or non-affirmation of LGBTQ people, nationalism and financial disparity.

To counter the downside of bounded sets, “we think the solution is to remove or make openings in the ‘fence,’” he said. “But that creates a fuzzy set, and the problem with a fuzzy set is we don’t have a compelling picture of Jesus.”

To be a healthy church or other faith organization, “we’re going to need to get rid of bounded and fuzzy sets altogether,” Capshaw insisted.

As an alternative, he returned to his agrarian metaphor and talked about how ranchers raise cattle in national forests. Instead of building fences, they drop resources for the cattle into the forests.

“If the cows want to live, they stay close to the source of life,” he observed. “They may wander, but not too far from the source of life.”

That method of ranching provides a good model for creating healthy churches, Capshaw said.

The source of life — “the shared center” — for churches is Jesus.

The source of life — “the shared center” — for churches is Jesus, he said, emphasizing that is not the same as saying “the gospel” is the center.

“We need something tangible,” he said. “The question is, ‘Which Jesus?’ Is it nationalism or social justice?”

The focal point of the center must be “the Jesus way,” he said, noting that way is defined by the Sermon on the Mount and the sacrificial example of Jesus. “Jesus on the Cross becomes the lens through which we must look,” he added.

Capshaw listed several attributes of the way of Jesus: enemy love; forgiveness; nonviolence, including in language and thoughts; radical hospitality; and making a place or giving a voice at the table without precondition.

“The only way this works is to center on love,” he insisted.

Changing metaphors, Capshaw invited participants to “imagine the solar system held together by the mass of the sun.”

“This is a model for the church — the beloved community,” he said. “It’s not going to change the outside world. But as the weight of Jesus gains mass in our lives and community, we will be more oriented not only to Jesus but to each other.”

When conflicts arise, Capshaw called for conversation that affirms the best of the other person and concedes weakness on one’s own side.

“Take the initiative to move closer to the other,” he encouraged. “It’s a difficult way of having dialogue. It takes a long time. … This is not easy; it’s tough.”

Even so, the stakes are high, he said, “because the world is watching.”