Witnesses at the campaign rally said they thought they heard firecrackers. Then the screaming started, and they realized the truth: a young man in his early twenties, a troubled loner, had out maneuvered security and was attempting to assassinate a leading presidential candidate.

But his target wasn’t Donald Trump; it was George Wallace, the same man Martin Luther King Jr. once called “the most dangerous racist in America.”

It wasn’t always that way. Even though Wallace began his political career in Alabama, the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement, he initially refrained from using race-baiting tactics. When the segregationist wing of the Democratic Party, the so-called “Dixiecrats,” rebelled against the party’s civil rights platform in 1948, Wallace did not join them. During his tenure as a state judge, he was known for his fair treatment of Black attorneys and plaintiffs. In 1958, he ran for governor of Alabama and was endorsed by the NAACP.

When Wallace lost that race to state Attorney General John M. Patterson, a strident segregationist backed by the KKK, he began to rethink his political strategy. In 1962, he used Patterson’s own schemes to defeat him, calling for “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” in his 1963 inauguration speech.

“I believe he used segregation and racism in 1962 for power, to win that election. I know he would have done anything it took to win that ’62 election,” said Wallace’s daughter, Peggy Wallace Kennedy. “To me, that’s worse almost than being a racist and segregationist in your heart.”

Security Guards close by, Alabama’s Gov George C Wallace, campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination, speaks at the Wheaton Plaza shopping center May 15, 1972. Later in the day, he was shot during a campaign appearance at Laurel, MD. Still paralyzed from the waist down. (Getty Images)

Governing as a racist

Wallace didn’t just run as a racist, he governed as one too. Only six months into his term, he staged a confrontation with Black students James Hood and Vivian Malone as they attempted to enroll at the University of Alabama. The KKK saw his segregation speech as a call to arms and bombed A.G. Gaston Motel, the home of A.D. King (brother of Martin Luther King Jr.), and Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which killed four girls and injured 14 to 22 other members in 1963.

“Much of the bloodshed in Alabama occurred on Gov. Wallace’s watch. Although he never pulled a trigger or threw a bomb, he created the climate of fear and intimidation in which those acts were deemed acceptable,” wrote Congressman John Lewis in a 1998 op-ed in The New York Times. Lewis was severely beaten by Wallace’s state troopers during the Civil Rights march from Selma to Montgomery, where protesters planned to plead their case before Wallace at the state capitol.

As his profile rose, Wallace waded into national politics. He ran for president as an independent in 1968 and as a Democrat in 1964 and 1972. Campaigning on a platform of white grievance, Wallace was adept at stirring up racial and class divisions. His method of tapping into America’s lingering racism became the standard playbook for Republican politicians who later would lean into this “Southern strategy” for their own presidential runs.

1972

Wallace began 1972 with three presidential primary wins and was doing well in national opinion polls when he began his stump speech on May 15 in the parking lot of a shopping center in Laurel, Md. It was after the speech that 21-year-old Arthur Bremer approached Wallace, while the candidate was shaking hands, and shot him four times — hitting him in the spine, abdomen and chest. Wallace was rushed to the hospital where surgeons operated on him for five hours. He would live, but he never would walk again.

US Representative Shirley Chisholm of Brooklyn announces her entry for Democratic nomination for the presidency, at the Concord Baptist Church in Brooklyn, New York. (Photo by Don Hogan Charles/New York Times Co./Getty Images)

One of those competing against Wallace for the Democratic nomination was Shirley Chisolm, the first Black woman elected to the United States Congress and the first Black American to seek the presidential nomination of one of the nation’s two major political parties. She had strong support among Black women, and although she knew it wouldn’t be enough to win the White House, she hoped to garner enough delegates to influence the eventual nominee to prioritize rights for women, Black Americans and Native Americans.

When she learned of the assassination attempt on Wallace, Chisolm insisted on visiting him in the hospital. “She came and prayed with him and talked with him. She shut her campaign down for a week,” said Wallace Kennedy.

Chisolm’s staff and supporters could not believe that rather than capitalize on the shooting, she would visit a racist segregationist. “I knew I was going to be thrown out of office. The people of my district came down on me like anything,” Chisolm said in an interview years later.

Future Congresswoman Barbara Lee worked on Chisolm’s campaign and remembered Chisolm saying, “Sometimes we have to remember we’re all human beings, and I may be able to teach him something, to help him regain his humanity, to maybe make him open his eyes to make him see something that he has not seen.”

During her visit with Wallace, Chisolm held his hand and told him, “God guides us.” When the doctor informed her it was time to leave, Chisolm said of Wallace, “He held on to my hands so tightly — he didn’t want me to go.”

Reflecting on that time, Robert Gottlieb, student coordinator for Shirley Chisolm’s presidential campaign, said: “She did not agree with anything Wallace stood for. There’s no question about that. But she understood that, if you really care about the country and you want to effect change, you have to embrace everybody. She was a true human being of sensitivity, commitment. And when he was shot, he was a human being in pain. And she wasn’t going to turn her back on him.”

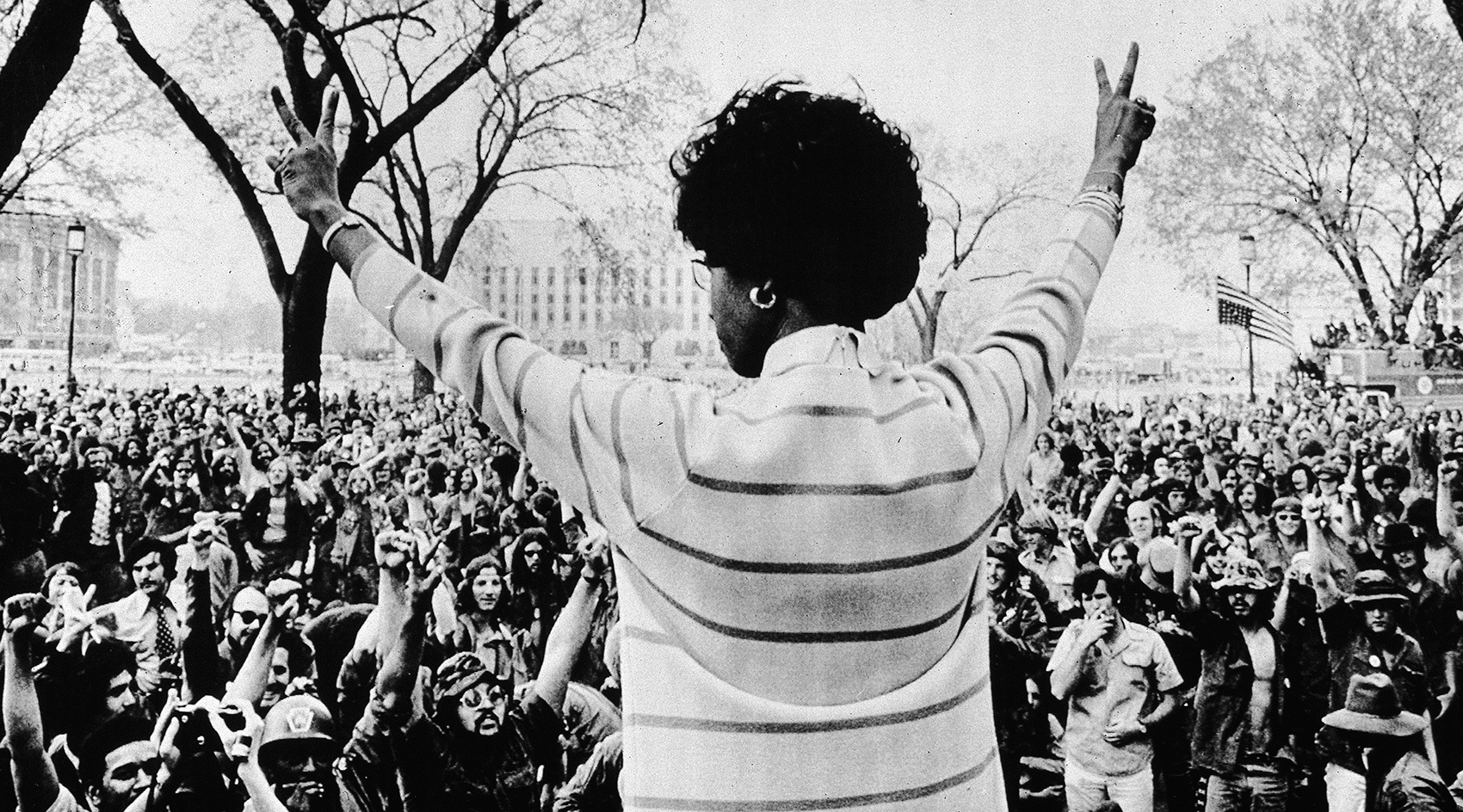

US congresswoman Shirley Chisholm gives the peace sign to a crowd of protestors as she speaks to veterans on the Washington Mall, Washington, DC, April 1971. (Photo by New York Times Co./Mike Lien/Getty Images)

‘A catalyst for change’

Chisolm served in Congress until 1981, eventually becoming secretary of the House Democratic Caucus.

“I want history to remember me … not as the first Black woman to have made a bid for the presidency of the United States,” Chisholm said, “but as a Black woman who lived in the 20th century and who dared to be herself. I want to be remembered as a catalyst for change in America.”

Chisolm was a catalyst for change in the country — and in George Wallace.

“Daddy was overwhelmed by her truth, and her willingness to face the potential negative consequences of her political career because of him,” said Wallace Kennedy. “Shirley Chisholm planted a seed of new beginnings in my father’s heart: A chance to make it right.”

The witness of Shirley Chisolm and the assassination attempt that left him wheelchair bound had a profound influence on Wallace, and he committed his life to Jesus Christ. In 1974, he told the congregation at Jerry Falwell’s Thomas Road Baptist Church in Lynchburg, Va., he had “been through the valley of the shadow of death,” and professed, “I am whole through the grace of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.”

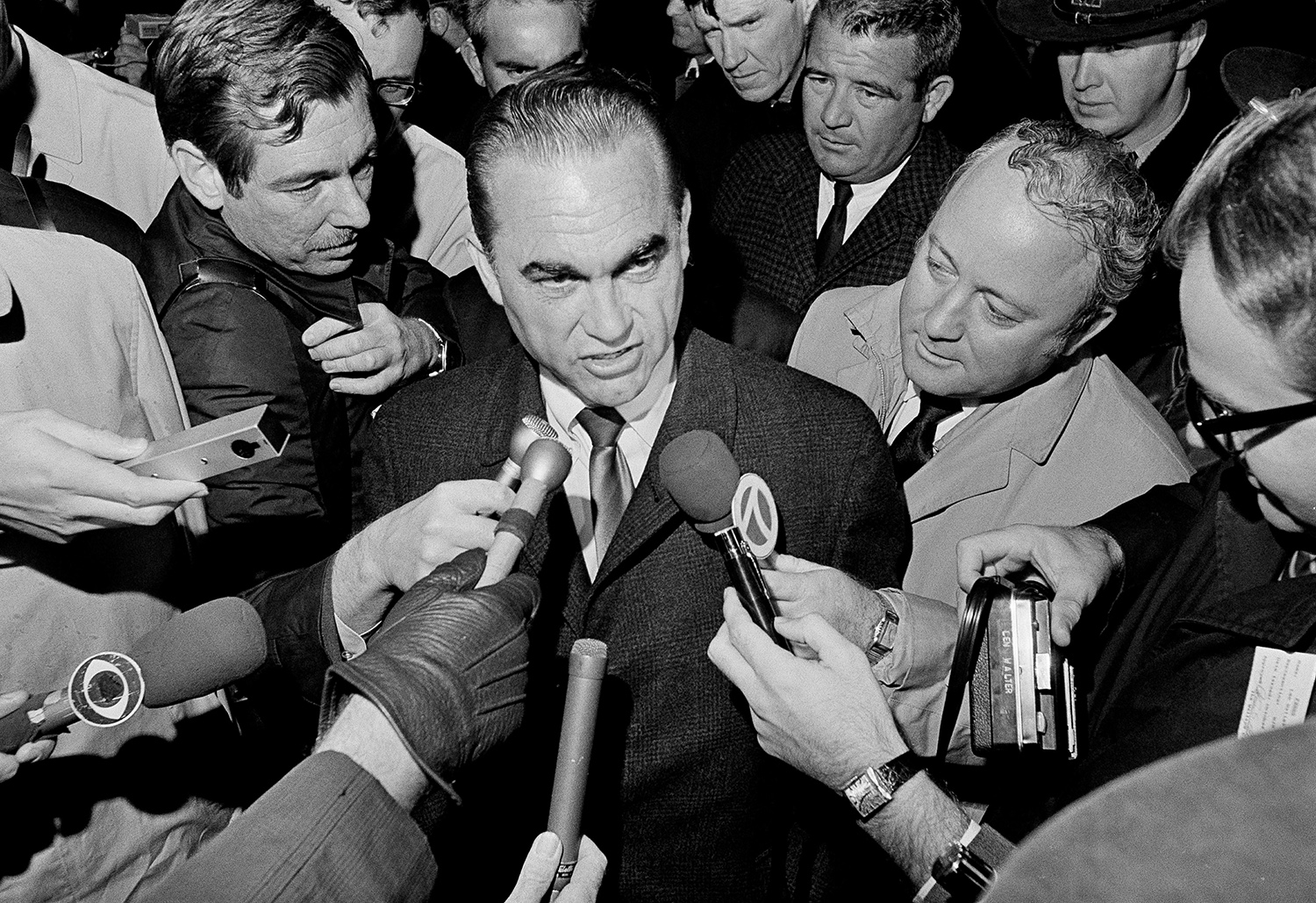

In this Oct. 29, 1968, photo, reporters surround presidential candidate George Wallace at Metro Airport in Detroit, Mich., after he arrived to address a night rally at Cobo Hall. Donald Trump promises to “Make America Great Again.” George Wallace said he would “Stand up for America.” . (AP Photo/Preston Stroup)

A changed man

And Wallace became a giver of that grace, not just a receiver.

Like Zacchaeus in Luke 19, Wallace saw the error of his ways and sought to make restitution. “He was a different person,” said Wallace Kennedy. “He needed the African American community to forgive him. His pilgrimage to the church was a sacred one I think.”

In 1979, unannounced, Wallace visited Dexter Road Baptist Church where Martin Luther King Jr. had once been pastor. “I have learned what suffering means. In a way that was impossible (before the shooting),” he said. “I think I can understand something of the pain Black people have come to endure. I know I contributed to that pain, and I can only ask your forgiveness.”

Putting these words into action, Wallace then rallied Southern Democrats’ support to pass Shirley Chisolm’s bill requiring the minimum wage for domestic workers. When he ran for governor of Alabama again in 1982, Wallace promised to increase jobs and equality for Black voters. He won — and kept his promise, appointing more than 160 African American members to state governing boards and doubling the number of Black voter registrars in Alabama counties.

“You are a different George Wallace today. We both serve a God who can make the desert bloom.

At a service commemorating the Selma to Montgomery march, NAACP President Joseph Lowery commended Wallace: “You are a different George Wallace today. We both serve a God who can make the desert bloom. We ask God’s blessing on you.”

Some have criticized the ease with which Wallace’s repentance was accepted and have pointed out it was white privilege that gave him the opportunity to apologize.

“When it becomes convenient for George Wallace, then he apologizes. But he made it seem OK to mistreat Black people in any kind of way. That was extremely damning,” explained historian Maurice Hobson at Georgia State University, where he teaches African American studies.

Filmmaker Spike Lee interviewed Wallace for his documentary, Four Little Girls, about the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Viewers have criticized Wallace’s attitude toward the Black people working for him as “embarrassingly patronizing.” During the film, the former governor desperately clutches the hand of the Black man who works as his nurse as if to reassure viewers he has truly changed.

John Lewis believed Wallace’s change was genuine: “I could tell that he was a changed man; he was engaged in a campaign to seek forgiveness from the same African Americans he had oppressed.”

It was important to Lewis that Wallace be remembered for his capacity to change. Peggy Wallace Kennedy agrees: “I hope history (will) define him as that person because not everyone has that capacity to change.”

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump is rushed offstage during a rally on July 13, 2024, in Butler, Pennsylvania.. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

A different response

Fifty-two years after the assassination attempt on George Wallace, Matthew Crooks, another fame-seeking loner, shot at former President Donald Trump during a campaign rally in Pennsylvania. The bullet grazed Trump’s ear but did no lasting damage.

Wallace Kennedy sees a lot of her father in the charismatic Trump: “They both realized that the two biggest motivators for voters was hate and fear.”

After the assassination attempt on Trump, there were calls for civility and unity from the Trump campaign. But it was evident in his speech at the Republican National Convention that the candidate himself was not going to adjust the tone of his vitriolic campaign by much or for very long. At a rally on July 28 in Minnesota, 15 days after his narrow escape, he told the crowd, “No, I haven’t changed. Maybe I’ve gotten worse.”

Many of Trump’s supporters, including evangelist Franklin Graham and William Wolfe, executive director for the Center for Baptist Leadership, saw the failure of the assassination attempt as “divine intervention.” They gravely misunderstand how God works.

The miracle is not in the bullet dodged, it’s in the heart changed.

It’s Shirley Chisolm putting her campaign on hold to visit George Wallace in the hospital and believing he could change when no one else did.

It’s Wallace apologizing and attempting to make amends, no matter how imperfect, to Black Americans.

It’s John Lewis, who almost lost his life marching to Montgomery, and yet was able to forgive Wallace beyond what he deserved. In Lewis’ words: “Our ability to forgive serves a higher moral purpose in our society. Through genuine repentance and forgiveness, the soul of our nation is redeemed.”

Editor’s note: This piece draws on quotations and background information from a variety of historical sources, cited in the hyperlinks where possible. It is not based on original interviews.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.

Related articles:

Let’s not return to the political violence of the past | Opinion by Richard Wilson

Parallels between the racist rhetoric of Trump and Wallace are undeniable. But there is one important difference | Opinion by Andrew Manis