In an election year in which Ronald Reagan could not be elected by his own Republican Party, some evangelicals have made a movie portraying America’s 40th president as a Christian saint.

Prior to the cultic adulation of the Trump era, Reagan was the most admired Republican president of the 20th century. While his rise from Hollywood to the Oval Office was fueled in part by the Religious Right, Reagan made no pretention of being a regular churchgoing Christian.

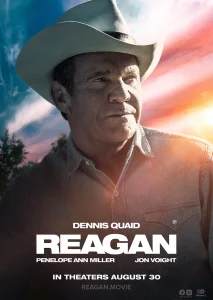

Now, the filmmakers of Reagan are hagiographers consumed by their zeal to polish Reagan’s life into a Christ-centered icon. The movie, with Dennis Quaid playing Reagan, debuts today.

The film’s portrayal of a young Reagan speaking at his church. (Photo: Cooper Ross)

Hagiography

Like the evangelicals intent on promoting the mythology of American as a “Christian nation,” the makers of this film seem determined to portray today’s evangelical faith as the true, God-approved faith, the faith embodied in Reagan.

Hagiography normally consists of writing the lives of the saints. The word also means “adulatory writing of the lives of the saints” or a biography designed to serve a political agenda. Hagiography of the less honorable kind is making a comeback, especially among evangelicals.

In promotion for the movie, Greg Laurie, senior pastor at Harvest Ministries, declares, “Ronald Reagan was one of the greatest presidents in American history, yet many have not known how significantly his faith in Jesus Christ shaped his life. … This dynamic new film, Reagan, tells this story and much more!”

Jim Daly, president of Focus on the Family, exults: “I highly recommend the new film about President Ronald Reagan’s life. This is not necessarily a political movie, but a movie about a political figure whose life and career were marked by courage, honesty, faith and deep conviction. This is a film for the whole family!”

The film’s portrayal of young Ronald Reagan working as a lifeguard. (Photo: Cooper Ross)

Reagan highlights the president’s key role in the Cold War. It follows him from the small town where he grew up to the glitter of Hollywood and then to the White House. It also portrays the spiritual formation of young Ronald Reagan, strongly influenced by his mother, Nelle, who dedicated herself to serving the Lord after a near-death experience, and his pastor who helped lead him to the Lord when he was 11 years old and baptized him.

The promotional video clip begins and ends with Reagan’s famous 1987 declaration to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to open the Berlin Wall, “Tear down this wall!” If this is meant to provide the context for Reagan’s Christian faith, let us remember there is more to being Christian than opposing communism.

That was an important moment in world history, but it was not a declaration of Christian faith.

Why now?

I’m glad people are talking about the Christian faith of Ronald Reagan. Conversations about the Christian life of any American president are welcomed considering the attempts of evangelicals to convert all our Founding Fathers into born-again evangelicals on the one hand and to portray Donald Trump as a faithful Christian on the other.

Even James Dobson struggled to make sense of Pentecostal televangelist Paula White announcing Donald Trump had been born again. Dobson referred to Trump as “a baby Christian.”

A larger question looms on the horizon: Why a film about Reagan’s faith in 2024 prior to the presidential election? Is this an attempt to connect the faith of the current evangelicals to the faith of Reagan and to the faith of our Founding Fathers? Is this an attempt to connect Trump to Reagan in order to make more sense out of the evangelical claims that Trump is “God’s anointed one”?

If the discussion were about whether a person is a Christian, somewhere in the conversations surely the question will come up: “How Christlike is this person?” In Biography as Theology, James Wm. McClendon argues that “the truth of faith is made good in the living of it or not at all.”

In what ways did the faith of Reagan embody the convictions of the Christian community, share the vision of the church and Jesus, exhibit the message and ministry of Jesus? How did Reagan correct or enlarge the community’s moral vision? Did he arouse impotent wills within the community to a better fulfilment of the purposes of God?

The film’s portrayal of young Ronald Reagan listening to a sermon. (Photo: Cooper Ross)

Reagan was a Christian

First, Ronald Reagan was a professing Christian. In Reagan’s own words, here is his testimony: “One thing I do know,” he wrote in 1973 to the pastor who nurtured him, Ben Cleaver, “all the hours in the old church in Dixon (which I didn’t appreciate at the time) and all of Nellie’s faith have come together in a kind of inheritance without which I’d be lost and helpless.”

He said: “I was raised in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), which as you know believes in baptism when the individual has made his own decision to accept Jesus. My decision was made in my early teens. … Yes, I do have a close and deeply felt relationship with Christ and believe I have experienced what you refer to as being born again.”

I’m not going against Reagan’s own testimony. Although I will make a case that Reagan’s understanding and practice of the faith was significantly different from his evangelical admirers.

To his credit, there’s an intriguing contrast between Reagan’s response to an assassination attempt and the response of Trump. Reagan declared his forgiveness of John Hinckley, his would-be assassin, telling his Presbyterian pastor: “I was really struggling (for breath), and I didn’t know if I would make it. God told me to forgive Hinckley. And I did. I forgave him. And immediately, I began to breathe better.”

Here is a primary example of following the direct teachings of Jesus not to seek revenge.

Reagan attributed his survival of the assassination attempt to the will of God. “I have decided that whatever time I have left is left for him,” Reagan told Catholic archbishop Terence Cardinal Cooke. Specifically, Reagan believed God had spared him so he and Soviet President Gorbachev could work together to end the threat of nuclear devastation in the Cold War. It turns out Gorbachev, as he revealed in 2008, was a “closet Christian.”

Reagan’s Christianity was individualistic

Reagan’s Christianity was as individualistic as his politics. A longtime adviser commented: “He cares about people as individuals. I’m not sure that he ever looks upon the masses and says, ‘I must do something, these are my people.’”

Sam Donaldson said of Reagan, “If you were down on your luck, and you got past the Secret Service into his office” (and said,) “Mr. President, I’m down on my luck,” he’d give you the shirt off his back. And then, in his undershirt, he’d sit down at his desk and he’d sign legislation … throwing kids off the school lunch program, other people off welfare, all in the name of fiscal responsibility. He had a good heart … but when it came to his ideology, his philosophy was ‘off with their heads.”’

The film’s portrayal of Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan together aboard Air Force One. (Photo: Rob Batzdorff)

Reagan’s Christianity was divorced from the church

Critics of Reagan’s brand of Christianity point out he didn’t go to church much. As president, he gave security restrictions as the primary reason. I am not going to dive into the murky waters of how much attending church has to do with one’s Chrisitanity. I am biased because I am a person of the church. I can’t distinguish my faith from my participation in the church. I am not applying that same standard to my investigation of the faith of Reagan. Holmes says, “America’s 40th president possessed the earnest faith of his mother, but the attendance record of his father.”

One story accents how Reagan was not at home on Sunday morning in church. He and Nancy attended a church in Middleburg, Va., one Sunday morning. As the couple went forward to receive Communion, Nancy said, “Ron, just do exactly as I do.” Nancy received her piece of unleavened bread, and as she dipped it in the chalice, she dropped it. President Reagan, following his wife’s instructions, took his piece of the bread and dropped it in the wine.

The story, as told to me, by the canon to the ordinary of the Diocese of Southern Ohio, adds that the assistant rector, holding the chalice, whispered, “We’ve got a floater.”

Not attending church but still being a Christian fits within the definition of many evangelicals now. David L. Holmes, in The Faiths of the Postwar Presidents: From Truman to Obama, reminds us Reagan prayed often, was a tither and didn’t take the name of the Lord in vain. Holmes says, “Throughout the two terms of his presidency, Reagan tithed to Bel Air Presbyterian Church. This record is rather remarkable.”

A critique of Reagan’s understanding of faith

My primary conclusion: Reagan’s faith fit the American idea of Christianity. He demonstrated a firm commitment to the definition of Christianity current among evangelicals. It is the faith of the 1950s, the American faith, the civil religion.

“There are people who want to take ‘In God We Trust’ off our money,” Reagan warned in one speech. “I don’t know of a time when we needed it more.” The defining issue in the coming election, he claimed, was “whether this nation can continue, this nation under God.” He also backed a constitutional amendment to restore prayer in public schools.

Reagan’s Christianity has more in common with that of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. He quotes Franklin and Jefferson far more than the Bible. Franklin was mostly a Deist. Jefferson is harder to label, but he was not an evangelical Christian.

Reagan’s Christianity has more in common with that of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. He quotes Franklin and Jefferson far more than the Bible. Franklin was mostly a Deist. Jefferson is harder to label, but he was not an evangelical Christian.

Reagan’s Christianity didn’t come into play in his cutting of the budgets making up the social safety net. During his administration, there was a marked rise in homelessness, especially among the mentally ill, and in teen pregnancy and drug abuse. These are not directly attributable to Reagan, but he didn’t see the need for the government to do more.

His administration made a slow response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In 1986, Reagan supported a cut of 11% in the small funding for fighting AIDS. According to the San Francisco Examiner, by the time Reagan publicly said the word “AIDS” for the first time in public, “21,000 Americans had already died from the disease.”

Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa condemned Reagan’s policy of going slow in eradicating apartheid. This was the gradualist approach to civil rights in the American South denounced by Martin Luther King Jr. Bishop Tutu called Reagan’s policy “immoral, evil and totally un-Christian. You are either for or against apartheid. You are either in favor of evil or you are in favor of good. You are either on the side of the oppressed or on the side of the oppressor. You can’t be neutral.”

Without question, Reagan was more at home with Billy Graham, W.A. Criswell, and Jerry Falwell than he was with Bishop Tutu and more liberal preachers in the United States.

The movie Reagan fits into the same category of evangelical attempts at Christianizing everything American. In this sense, it is not so much about Reagan as it is about the continued attempt to baptize America as a Christian nation in its founding and in its current existence.

“The Christianity of Eisenhower and Reagan represents the earliest version of Christian nationalism.”

In the 1950s, conservative America was determined to overthrow FDR’s “New Deal,” his political embodiment of the Social Gospel. And they used Christianity to spearhead the movement. What matters here? Reagan shared this vision. Like the incipient Gnosticism of the early second century, the Christianity of Eisenhower and Reagan represents the earliest version of Christian nationalism.

Corporations used clergymen in their PR war against Roosevelt’s New Deal, and Billy Graham helped Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon use religion as the “lowest-common denominator” to unite the public.

Here, Reagan’s faith has more in common with Eisenhower’s civil religion. Reagan and Eisenhower, like many American presidents, understood the significance of faith to the American people. They, in a sense, used faith as the founding fathers did — to promote the health and vitality of democracy and for the good of the nation.

In the final analysis, Reagan’s Christianity looks like today’s political evangelical faith. The strong sense of individualism combined with a deep strain of religious populism, a separation of faith from social action and government “interference,” a strong belief in the trappings of religion being instituted by law (prayer in public schools), and an unwavering opposition to communism.

Reagan especially saw Christianity in terms of its opposition to “godless communism,” an appealing description of religion for a president in the midst of a cold war.

“In Reagan’s two terms, being anti-communist was enough for one to claim he or she was a Christian.”

Reagan embraced the individual Christian approach to the neighbor and the hard-nosed political approach to the masses of the poor. In Reagan’s two terms, being anti-communist was enough for one to claim he or she was a Christian. Among today’s evangelicals, being anti-abortion seals the deal for Christian bona fides.

Reagan’s Christian faith has become a full-grown Christian nationalism, a faith more nationalistic than Christian, a faith more idolatry than faithfulness to the teachings of Jesus. Evangelicals can claim Reagan as patron saint, but it turns out Reagan’s commitments to Christ probably exceeded that of today’s crop of Christian nationalists.

If the film Reagan wants to remind us President Reagan was a master communicator and a diligent opponent of communism, that alone is worth watching. I often cry when I hear, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

But if the movie represents an attempt to tie America’s founding to Christianity, it fails.

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor and writer in New York state. He is the author of 11 books, including his latest, Dancing with Metaphors in the Pulpit.