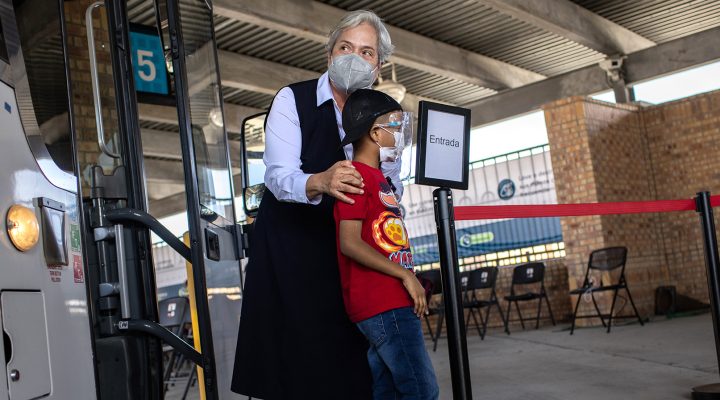

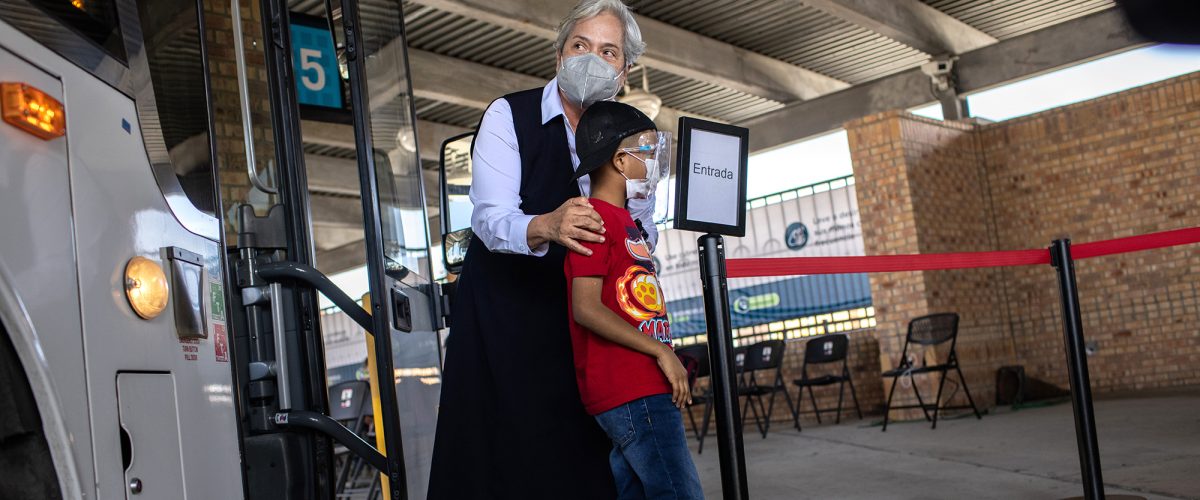

Sister Norma Pimentel wants Americans to see children held in detention centers along the U.S.-Mexico border as human beings.

Although she has been persecuted by other conservative Christians and even her fellow Catholics — like Texas Gov. Greg Abbott — for showing compassion for immigrants, the South Texas nun has no plans to stop sharing the love of God, she told a group of journalists and religious leaders.

Pimentel was a keynote speaker at a symposium celebrating the 90th anniversary of Religion News Service held at Fordham University in New York City Sept. 10.

Norma Pimentel

Her latest journey into advocacy for migrants began in 2019 when she heard there were thousands of unaccompanied children being held in U.S. immigration detention centers but she never saw any of them in Catholic shelters. Organizations operated by Catholic Charities and other faith-based groups like Fellowship Southwest often house or help migrants as they pass through border communities.

“I asked a local judge to get me permission to enter the detention facility,” she explained. “I was hearing that there were so many children at the border, unaccompanied kids that were in great thousands of numbers, but I wasn’t seeing them. I was seeing families with their kids released. And so we were responding to that. So I asked him, please give permission so I can enter those detention facilities where these kids aren’t supposed to be.”

With persistence, she finally gained permission, “and that encounter I faced when I saw those children truly grounded me to understand the role and the purpose of who we are as people and our role into what we must be doing to save humanity, to save these children,” she said.

“They were all dirty, faces gray from crossing the river and the mud drying in their skin and their clothing, and the cells were packed with them.”

“It was a small facility that is simply used to process immigrants and determine what to do with them. It’s not equipped to handle people beyond a couple of hours, maybe a day at most. And it was full with children, little ones, chiquitos, not more than 10 years old. They were all dirty, faces gray from crossing the river and the mud drying in their skin and their clothing, and the cells were packed with them.”

As she stood on the outside of a big glass window, she asked the detention officer if she could go inside the packed rooms and pray with the children.

“The children were just, their little faces were looking out and looking at us, all of them, their little faces full of tears, just those eyes,” she recalled.

The guard said no, it would not be possible.

“And of course I said, ‘But I want to pray with them!’ And how can you say no to a nun who wants to pray? Right? So I got in.”

What happened next was “the most difficult thing I’ve ever done in my life,” she said, “to walk into this one cell with children, barely able to get myself into the center of that cell. And all of them surrounded me, pulling my dress, looking up with tiny little faces, crying, telling me ‘Sister, please get me out of here.’”

In that tender moment, the nun “started crying with them,” she confessed. “And I said, ‘Let’s pray. And they said, ‘God, please help us.’ And they prayed with me. And the officers, they were looking silent and they, too, were crying.

“When I walked out of that cell, the officer in charge told me, ‘Sister, thank you. You helped us realize they’re human beings.’”

“The officer in charge told me, ‘Sister, thank you. You helped us realize they’re human beings.’”

And that’s the point of Christian ministry in such places, she said.

“We let our jobs, our responsibilities, our laws and our whatever tell us and dictate to us how we must be,” she lamented. “But that connectedness to our humanity is our connectedness to God. That is God within us, that tells us who we are and what we need to stand up for and what we must say and how we can use our voice, our presence in making sure that every person we encounter in our life, no matter who that person is, we treat with the utmost dignity and respect.”

In doing this, “we help them realize that they, too, are a child of God,” the nun said. “That is truly the only mission we have in life. Why is it that we lose sight of it and we let others, as I heard the word here — hijack — why do we let others hijack our faith, our identity of who we truly must be?”

This work at the border is never-ending, she explained. “What I see is families struggling, mothers that all they care about is to protect their child. That you can hold a young boy who’s crying because he misses his dad and will hold them tenderly and try to help him calm down.”

“Every day I see a shelter that is filled with families. We have mats on the floor so they can lay down in the evening. And 2019 was the year we had the most people I have ever seen in our center,” she reported. “Almost a thousand people arrived every single day. There’s no comparison today. When they say today, ‘It’s the worst it’s been,’ no, it’s not. It was back in 2019 when we were seeing so many people that we were receiving.”

In those days, though, she and other volunteers witnessed the grace of God’s inclusive love, she said. “When I didn’t have any more space to put anybody in that room and they walked in at night, the families would just move. ‘There’s space here, there’s space with us.’

“It is this understanding of humanity that we must be able to not let others steal from us,” Pimentel said. “We must own it. We must make sure that we pass it on and leave it out, be our very best so that others can also be their best as well.”

Related articles:

By word and deed, Pimentel urges CBF participants to “stand up” for migrants

Another Paxton attack on migrant ministries in El Paso stopped by a judge