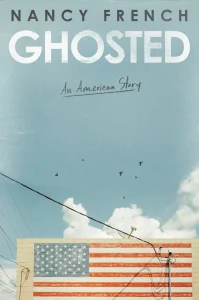

I’ve known Nancy French for some years now, if by “know” we count social media connection, which I do. I’ve gotten out of the habit of talking about disagreements with people; I look for places of connection and ask whether people are connected to my core Christian values, which Nancy and her husband, David, are and always have been. Nancy’s brilliant new memoir Ghosted: An American Story tells the hard-scrabble story of her upbringing, her love for David and their children, and her quest to hold onto authentic faith when her Christian tradition embraced Donald Trump and secular power. As Ghosted reminded me, Nancy also is an incredible advocate for women and children who have been harmed by Christian institutions. Her work is essential reading, and I am so grateful she found the time to offer these hard, beautiful responses to my questions.

Greg Garrett: While Ghosted is a lot of good things — spiritual autobiography, artist’s memoir, tales of a marriage and family — as a teacher, one of the pieces I was most drawn to was that it is the story of a smart and talented woman who found her own voice. The book is that story, of course, but could you briefly share with my audience a bit about how you stopped being a ghostwriter for the Republican Party and began to explore and tell the stories that were not being told? Did writing the book have a bearing on why you decided to publicly share so much of your battle with cancer?

Nancy and David French after she rang the bell to signify completing cancer treatments. (Photo: Facebook)

Nancy French: Thank you for describing me as a smart and talented woman. My college professors might disagree! I’m a college dropout who learned to write well, which gave me the opportunity to write for GOP celebrities and others. At one point, I was ghostwriting for former governors, senators, pundits and the wife of a presidential candidate. This was great, since these clients aligned with my values and principles, and I considered myself grateful that I was able to align my work with my conscience. (I was the kid with photos of Ronald Reagan on her wall.)

When Donald Trump mocked John McCain’s military service, however, I was jolted. I believed the GOP would not tolerate such mockery of a man for his military service, since my entire life Republicans had claimed to be pro-military. Suddenly, the conservative movement shifted, and I was left baffled.

“My faith didn’t allow for mockery of a war hero, disabled reporters and immigrants.”

I encouraged my clients to push back on this shift, to try to preserve the GOP as the party it had been. But my clients were either on the “Trump train” or were hoping to hop on. Eventually, they got sick of my pushback, which was understandable. Ghosts aren’t hired to push back and question; they are supposed to faithfully represent their clients’ wishes. But that word “faithfully” bothered me. My faith didn’t allow for mockery of a war hero, disabled reporters and immigrants.

I quit or was fired by all my clients. Because I had no college degree, I was basically unemployable.

When former Fox host and activist Gretchen Carlson told me about a camp in Missouri called Kanakuk that had some issues with hidden abuse, I was therefore free occupationally to pursue the story. In other words, I had some free time. And I do really mean free. I quit or was fired from all of my jobs and decided to pursue this on my own dime.

I didn’t want to look into abuse, but — as a grown woman — I also could not sit idly by while children were at risk.

Since no major newspaper was willing to take on this cause, I was able to successfully teach myself to be an investigative journalist. I launched a three-year investigation into the camp, the results of which landed in USA Today.

I wrote Ghosted and included the story of how I lost my GOP clients and switched to investigative reporting. As I was finishing up the edits on the book, I received terrible news: I had cancer.

“I wanted to inspire others and normalize what cancer looks like.”

I decided to publicly deal with my cancer in a transparent way — namely because it’s such a horrifying development and I knew I needed prayers and support. As my hair began falling out and I knew I needed to shave my head, I saw a woman in a Chicago museum who had a bald head. I immediately went back to my apartment and cut off all my hair. Like the unknown woman in Chicago, I wanted to inspire others and normalize what cancer looks like. I began posting photos of my bald-as-an-eagle self and found that it was empowering for me and others.

GG: You and your family have lived the culture wars in ways many of us couldn’t imagine if you and David had not shared your experiences. I can’t imagine what it was like to be the constant subject of racist and hateful posts and sexual images and innuendo. How did you cope with the attacks? You’ve maintained a social media presence despite all the hate you’ve encountered. What advice would you give readers who experience pushback on those platforms but feel for whatever reason that they need to remain to offer a message?

NF: I am not sure how to handle the constant hate and condemnation on social media. I’ve developed a heavy “block” hand and have tried to curate it as much as possible, but no one should ever be able to accommodate the kind of hatred and sexual humiliation that comes my way. This level of social ostracization is real and painful. Therefore, the people who just shake off the criticism as “a part of doing business” really miss out on an important opportunity to grieve what has happened to our nation.

NF: I am not sure how to handle the constant hate and condemnation on social media. I’ve developed a heavy “block” hand and have tried to curate it as much as possible, but no one should ever be able to accommodate the kind of hatred and sexual humiliation that comes my way. This level of social ostracization is real and painful. Therefore, the people who just shake off the criticism as “a part of doing business” really miss out on an important opportunity to grieve what has happened to our nation.

GG: Your life has been affected by the presence of predators in the church and by the unwillingness of churches and parachurch organizations to demand accountability from pastoral figures. Why do you think churches have been so bad at removing ministers from positions of authority? What does it say about American Christianity, or parts of it, that sexual assault continues to be an issue?

NF: I don’t really have the answers. I investigated Kanakuk Kamps for three years, believing if I could expose the horrors there that Christians would respond in a gigantic expression of outrage. Instead, my investigation was met with a big ole evangelical shrug. This camp has had multiple predators, including one that abused/sodomized an estimated “hundreds” of campers. I have been told of 17 Kanakuk-related victim suicides. One predator, when caught, killed himself. That is some serious evil to overlook!

“Nobody resigned as a result of the failure to stop a decade of abuse.”

Yet nobody resigned as a result of the failure to stop a decade of abuse. There was no disciplinary action against any of the predators’ supervisors, Joe White is still the head of the camp today, and the camp has been full even after the investigation. Get this: Christian singer Michael W. Smith still promotes the camp. Max Lucado and Tim Tebow are still on the Kanakuk Bible app!

I have no answers as to why. But I do know that Christians have a very easy time accepting that Bill Clinton and Harvey Weinstein were abusers. (That’s what liberal ideology brings, they say.) But when it comes to Deacon Jack or Preacher Bill, however, they turn a blind eye. I’ve seen this over and over and over, across denominations. It’s devastating.

GG: Following up on that, the Republican Party and evangelical Christianity have made what feels to many of us like an unholy bargain. Donald J. Trump is again the Republican candidate for president. You write beautifully and sadly about what American evangelicals have lost by throwing in with this man. Can you summarize why you and David stepped away from this partnership? I know it feels that you’ve lost so much. What would you say you’ve gained?

NF: I decided in 1998, when Bill Clinton famously did “not have sex with that woman,” that character in presidents mattered. I believed it then and believe it now, so that meant a break from the Republican Party I’d so loved.

We’ve lost a great deal. However, I have a clean conscience.

I’ve also been able to relax some of my preconceived notions about what a “good person” is. I used to believe there was a stark line between good and bad people and you could tell it every Sunday morning by whose cars are and are not parked in the church parking lots. I was wrong.

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts,” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn writes. “This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained.”

“We’ve lost a great deal. However, I have a clean conscience.”

In other words, the separating line between good and evil is within us. We therefore individually need to work out our own salvation with fear and trembling.

I’m thankful to have had my paradigm shift on this issue. It opens up a world of friends who are on different sides of the political aisle — people I’d unfairly judged before I realized that I, myself, had participated in unfair mischaracterizations of my perceived political neighbors. As a political ghostwriter who specialized in “owning the libs” for so many years, I realized I was bearing false witness against my liberal neighbor.

That was my mistake, and I confessed all that in my book.

GG: The closing chapter of your book, “Listen,” offers such a powerful acknowledgement of God’s presence — it made me think of what Anne Lamott calls “God as Sam I Am,” that thing where the Holy Spirit throws billboards and songs in front of us that we need to hear. As you’re listening for God these days, where do you hear and feel God moving in your life? What gives you hope in these fractious times?

NF: The world is so crazy now, and it frequently seems like my husband, David, and I are all alone, attempting to navigate the political landscape while our former friends spew invectives at us. However, there’s something liberating about no longer carrying water for a political party that has rejected the values I hold dear. There’s something freeing about knowing who your friends are and are not.

When everything is stripped away, it’s easier to remember that God is the only constant ally and friend. He is there even when you feel politically, spiritually and even culturally homeless.

“The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man hath nowhere to lay his head,” Jesus said in Matthew 8. Surely we can similarly say, “The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests, but the conscientious American citizen hath nowhere to declare a political affiliation.”

It’s not really that much of a sacrifice, when you look at it in the context of Jesus’ sacrificial love for us.

God lovingly reminds us that this world is not our home. We have to get comfortable in this discomfort, recognizing it as a holy and sacred space.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

More from this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Robert P. Jones

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Brian Kaylor

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Colin Allred

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Tia Levings

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Linda Livingstone

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Samuel Perry

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jimi Calhoun

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with David Dark

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Randolph Hollerith

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jillian Mason Shannon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Vann Newkirk II

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Sarah McCammon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Winnie Varghese

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Kaitlyn Schiess

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Russell Moore

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Ty Seidule

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jessica Wai-Fong Wong