Jessica Wong is the author of Disordered: The Holy Icon and Racial Myths, an ordained elder in the Presbyterian Church (USA), and teaches systematic theology at Azusa Pacific University. I was drawn to her work because like me she is writing and thinking about whiteness and racism in America and about some of the myths and images that define it. But as she also writes out of a very different identity than mine, I was fascinated by her book and by how her own personal story is interwoven with her conclusions. I am so grateful to Jessica for the chance to talk about race, religion and politics.

Greg Garrett: In your 2021 book, you wrote about your personal relationship to this topic and why you felt drawn to write. Could you share a little about how you have encountered racism even though, as you put it, Asian Americans are sometimes regarded as “honorary whites” when that notion is useful for white people?

Jessica Wai-Fong Wong

Jessica Wong: Often the term “racism” is used to describe overt, racially based bigotry. According to such a definition, one might say Asian Americans are not subject to significant instances of racism today. Of course, we have episodes in U.S. history like the Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese Internment and, more recently, the xenophobic violence against Asian and Asian Americans during the pandemic, but in comparison to, say, the long history of slavery, lynchings, police brutality and mass incarceration of the Black population, the Asian American experience seems to pale.

The problem with such a narrow conception of racism, however, is twofold.

First, it allows most people to simply say they’re not racist and the problem of racism is only an issue for a small portion of the U.S. population. End of conversation.

Second, this narrow reading of racism pushes us toward a kind of Suffering Olympics that divides and pits us against one another as we compete for our pain to be acknowledged and for access to limited resources to aid us in the fight for our own racial group.

I find it’s more helpful to focus instead on the larger system of race that privileges whiteness or, as I put it in my book, the “racial logic” that from an early age and often without our knowing shapes how we — as a society — imagine one another and, in turn, engage in the world. By approaching the problem in this way, we’re able to more readily address racial stereotypes, unconscious bias, skewed conceptions of beauty, culture, humanity, progress and unjust systems.

As so, while I can tell personal stories about pandemic aggression or the perpetual foreignness implied in compliments about how well I speak English, my native language, I also can point to the anecdote I shared in Disordered about my 5-year-old self wondering whether I could pass as white. That, too, is a manifestation of the problematic racial (or racist) logic that has poisoned our social imaginary and informed the perverse way in which I learned to make sense of the world and myself. Even the “honorary whiteness” achieved by certain Asian Americans can be understood as a sad consequence of this same racialized way of imaging and organizing the world vis-à-vis the promise of whiteness and racial hierarchy that it creates.

“The problem is a racialized way of imagining and ordering the world to which we’ve all been exposed in one way or another.”

The last thing I’ll say about this broader approach to the problem of racism is that it creates space for all people to participate in the solution. It recognizes the problem extends far beyond particular racist people. The problem is a racialized way of imagining and ordering the world to which we’ve all been exposed in one way or another. This means it’s possible to be a white person and be actively struggling against this troubled racial logic, just as it’s possible to be a person of color and be perpetuating it. Recognizing the larger racial logic that impacts us all, albeit in different ways and to various degrees, but impacts us all nonetheless, is an essential step in the process of dismantling this unjust racial system, together.

GG: Has your perception of how dark bodies are regarded by white Americans changed in any way since you wrote the book? Where do you see your current research headed?

JW: I’ll begin by saying I don’t think the problem is simply the dominant way in which white Americans have been taught to view dark bodies as disorderly. It’s the dominant way in which we have all been taught to imagine the world through the lens of the given racial hierarchy.

JW: I’ll begin by saying I don’t think the problem is simply the dominant way in which white Americans have been taught to view dark bodies as disorderly. It’s the dominant way in which we have all been taught to imagine the world through the lens of the given racial hierarchy.

As for whether my views have changed, I think, if anything, I’ve gained a more thoroughgoing sense of the breadth of our societal obsession with proper (sacred) order and our fear of disorder as well as those who embody it. The dark bodies of Black, LatinX, and Amerindian peoples are simply one iteration of this.

There’s a lot more to say about how our theologically charged conceptions of order and disorder have influenced the way in which the bodies of various groups have been viewed and treated throughout the history of our country, something I only gesture toward in the book. Here, I’m thinking, for example, about the embodiment of people with disabilities, transgender individuals, and women — perhaps most notably within Christian circles, the embodiment of women with regard to sex, sexuality and abortion.

I’m currently working on two books. The first, Black Monsters, Yellow Ghosts, is concerned with tracing how the racial logic that leads to Black hyper-visibility in society, insofar as the Black population is more often registered as a disruptive threat to our proper societal order, is the same logic that produces Asian American invisibility and erasure. While the system manifests differently with respect to distinct racial groups, it is still the same system at work. My hope is that we might recognize that, despite the siloing consequences of race, the Black struggle is not isolated from the Asian American, is not isolated from the Amerindian, is not isolated from the LatinX, etc. The truth is that our fates are tied, and to struggle for another people’s liberation is part of struggling for our own.

“Our fates are tied, and to struggle for another people’s liberation is part of struggling for our own.”

My second project considers the possibilities of the Spirit’s work of delight and how it can function as a powerful and transformative resource in addressing the epidemic of anger, exhaustion and disconnection that colors the social and political reality of our day. I’m particularly interested in how delight can fuel the work of justice, foster community and perhaps even play a part in transforming the troubling ways in which people have learned to see and navigate the world.

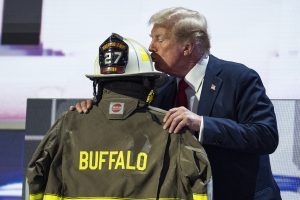

GG: I’m struck by how you note in your book that white men, even early into the colonial enterprise, believed that darker and indigenous people were poisoned and infected. It sounds eerily like Donald Trump’s recent rhetoric about dark people and immigrant people poisoning the blood of America, or at least of white Christian America. As we enter into this election year, what are some of the concerns you see in your family or community? What are some of your broader concerns for our country?

JW: Absolutely. I thought the same when I heard Trump’s Hitleresque statement. Sadly, this conviction that the presence of those who are unlike us pose a dangerous, even demonic threat to our proper societal order and, with it, to our way of life has been a reoccurring theme throughout human history.

This is not to say we don’t need real immigration reform. We do. But the question is whether we are willing to come together to try and solve the problem or are so entrenched in our camps wherein we demonize the other party that we refuse to even engage those who think or see things differently.

“Goodwill, hope and authentic encounter seem to be a thing of the past.”

Goodwill, hope and authentic encounter seem to be a thing of the past. What we saw in 2020 was fear-fueled anger that, left unresolved, resulted in increased polarization, violence and feelings of isolation. I suspect we’ll see more of the same and to an even greater degree this election cycle. This highly polarized and disengaged way of relating to those outside of our established camps makes the call of the faithful to embody the alternative relational order of Christ all the more urgent.

GG: I’m always drawn in my own work to the way literary, visual and material culture supplements the stories and myths Americans tell about themselves and the Other. Your book uses advertising, pulp adventure and other artifacts to demonstrate the pervasive racism of many American myths. What are some contemporary cultural manifestations of these damaging myths that you would call out for us? What are some of the stories and images pushing back or providing necessary correctives to the myths you write about in your book?

JW: There are plenty of contemporary examples of how problematic racial narratives continue to circulate within our society (for instance, Rudy Giuliani’s defamatory claims that election workers Ruby Freeman and Shay Moss were passing around USB drives “like they were vials of heroin or cocaine.”) When it comes to challenging the problematic racial narratives that continue to haunt our social imaginary, it seems as though one of the most effective ways to do so is through popular cultural depictions that serve to normalize and humanize people of color and their experiences.

Minari is a beautiful example of a film that tells the story of a Korean family’s immigrant experience and their own search for the American dream. We might also point to the diversification of the hero trope with films like Black Panther, Shang Chi and the most recent Spiderman movies.

However, when we crunch the numbers, with the exception of Asian Americans, studies show there has been very little progress in on-screen representation of people of color over the past 15 years. So, while we should certainly take note of the counter-narratives that exist, we must also recognize there is still quite a bit of work left to do.

GG: White Christian nationalism has come roaring back into prominence in the past few years, and white church leaders, media figures and politicians are often saying the quiet part out loud. It seems to me Christians who don’t share racist notions of white privilege have a responsibility to step up and do better theology, offer better readings of the Bible. As a liberation theologian who thinks about race and justice, what wisdom could you offer white readers about how to counter these notions by citing the Scriptures and the tradition? Or do these sacred arguments still speak to such people? If not, what are the human arguments that might echo?

JW: I think that you’re onto something when you raise the question of whether white Christian nationalists (or really any of us) can be persuaded to change our worldview through reasoned argument, whether based upon Christian Scripture or human values. I suspect part of the appeal of extremist groups is that they provide those who feel disenfranchised and isolated an explanation for their lived experience, a means of exercising agency and a space of belonging. Even the soundest theological reasoning will be hard pressed to loosen the commitment that comes with such deep feelings of belonging and identification.

Instead, I wonder whether the starting place is to offer a counter-community, a space of compassion and belonging even for those with whom we may adamantly disagree. This doesn’t mean eschewing real conversation. But, as Loretta Ross suggests, persuasion is not going to occur by calling people out and ostracizing them. Instead, we need to invite people into a new space of belonging and, with it, a different way of seeing and being in the world.

GG: I was heartened by the strong sense at the center of your book that through Jesus, the true icon of God, we can yet find hope and healing. That’s at the heart of my own faith. In your research and teaching and in the larger church, where are you finding encouragement for the possibility of liberation and reconciliation? What are some spiritual or practical actions we can be taking to build Beloved Community? How can we be faithful to that true icon of the divine as we engage with American public life?

“It’s both easier and safer to surround ourselves with people who are like us than to engage in the hard work and risk involved in connecting with those who are different.”

JW: One of the most painful aspects of our country’s engagement in public life is that we’ve found it’s both easier and safer to surround ourselves with people who are like us than to engage in the hard work and risk involved in connecting with those who are different. The consequence of this tendency is that it leaves us cut off from one another.

The call of Christ is a call to an altogether different kind of relational order — an inclusive relationality characterized by true openness to authentic encounter even with those who are different from ourselves. The Spirit’s relational movement witnessed to in Scripture is both transgressive and expansive.

It is marked by an outwardly moving, radical inclusion created through the joy of authentic connection. It is marked by the creation of something new; of a wholly new, unexpected community. This is the relational reality of the Spirit; the same relational reality belonging to Christ; the same relational reality into which we, too, are being called. Instead of isolation and fear, we are being invited to draw toward one another, to connect, to be vulnerable, to be truthful, and to do so bolstered by the love of God — a love that is always with and for the other.

As idealistic and seemingly impossible as this relational order may sound, especially within our current social and political climate, there are nonetheless spaces wherein we see this radical relationality being lived out.

We might point to the Community First Village in Austin, Texas, as one profound example. This ministry was born out of and is sustained by relationship, by connection. In fact, it is this relational connection, the willingness to encounter and recognize others in the fulness of their humanity, that makes this tiny house project so different. Instead of basic, utilitarian structures intended for emergency housing, these houses are built for people to stay permanently. Each house with its own personality, residents are able to choose their home, care for it, put down roots and, most importantly, become a part of a close-knit, supportive community that knows and cares for one another.

Of course, faithfulness doesn’t necessarily entail beginning a radical new ministry that solves the problem of homelessness or racism. We don’t need to fix the systemic injustice of our city in order to be faithful. Instead, the call of the faithful is simply to open ourselves up to encounter with the other, open ourselves up to connection — connection with one another, connection with the natural world, connection with the divine and, in turn, connection with ourselves.

Such connection is participation in the holy order of the Triune God who is always with and for the other, always bound up in the relationality that is the divine perichoretic dance. And so, while the problem of isolation that we face today is severe and, at times, can feel overwhelming, the answer is simple. Faithfulness is a life oriented toward connection with the other. This is at the heart of the holy order of God. This is the relational reality of Christ. And this, in essence, is our participation in the divine.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles in this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.