This article discusses suicide and suicidal ideation. If you are in crisis, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

You know someone, even if you don’t know it.

You work with someone. Go to school with someone. Tailgate football games with someone. You love, like or care about someone who has or is currently struggling with thoughts of suicide.

“Even if you’ve never been directly impacted by suicide, someone you know or love has been,” said North Carolina youth director Will Busch (known by his youth group as “Willy B”) in an interview with BNG. He says church leaders and goers “need to recognize their proximity” to issues of mental health and destigmatize conversations about it in faith spaces.

“There is a toll,” Busch said.

While Suicide Awareness Month is a good time to talk about mental health in church, it is a relevant topic year-round. With world tragedies on constant social media display — often coupled with traumatizing images or videos — and the typical milieu of day-to-day life stressors big and small, it’s safe to say church members everywhere have experienced some kind of psychological anguish or pain.

And moving out of September, there are many ways ministers can be present to these issues throughout the year.

The facts

Ministers can start by knowing some facts about mental health and suicide.

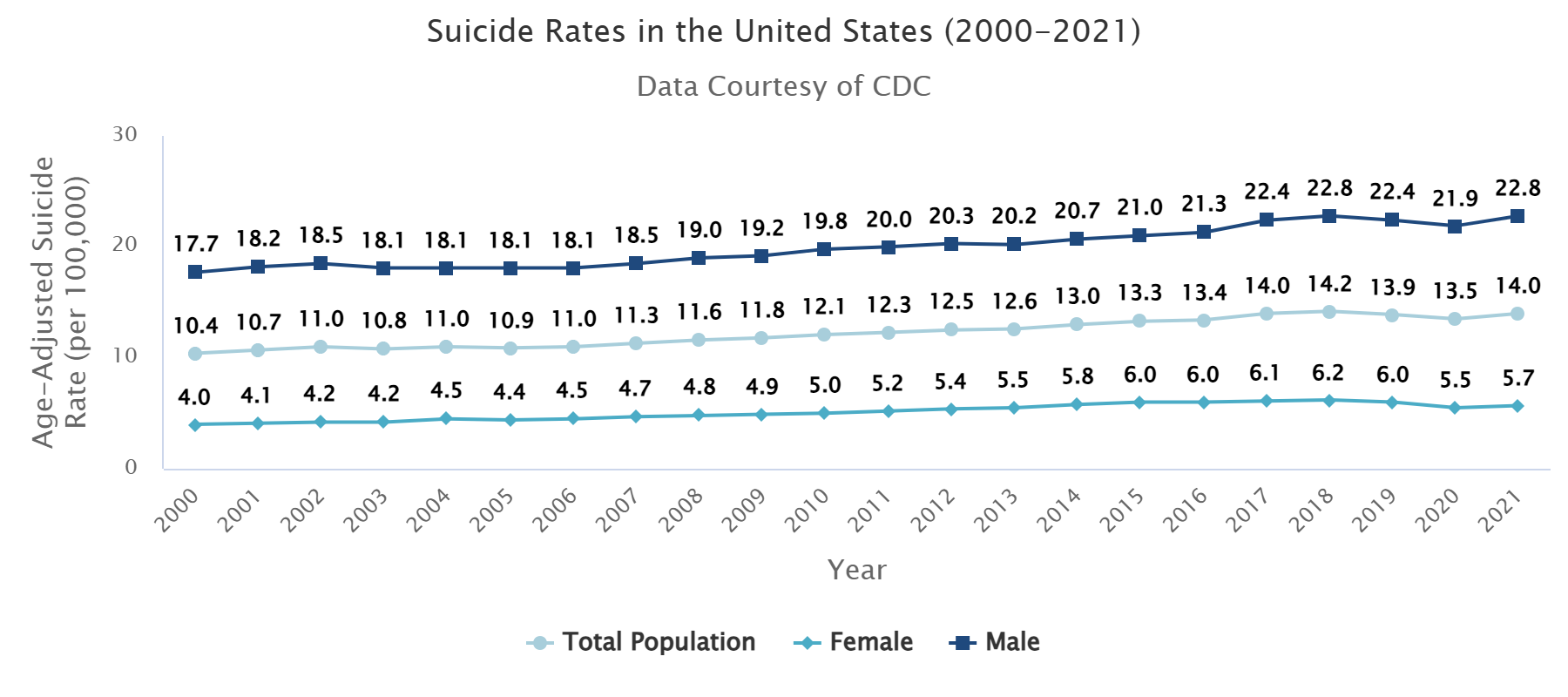

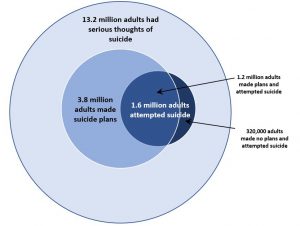

A 2022 study published by the CDC estimated that between 2015 and 2019 in the United States, 10.6 million adults experienced suicidal ideation. 3.1 million made suicide plans and 1.4 million made suicide attempts.

“It is the second leading cause of death for adults ages 25 to 35.”

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, “suicide is a major public health concern” and is “among the leading causes of death in the United States.”

It is the 11th leading cause of death in the U.S. for all ages.

Broken down, it is the second leading cause of death for adults ages 25 to 35 and kids ages 10 to 14, and third for young people ages 15 to 24.

The NIH defines suicide as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with intent to die.” Likewise, the term “suicide attempt” describes a nonfatal instance of this behavior, and “suicidal ideation” describes “thinking about, considering or planning” this behavior.

All too often, those struggling with suicide lack a trusted community to talk about their mental health. And while mental health issues like suicidal ideation can seem difficult or taboo for faith communities to talk about, belonging to a church or another faith organization where leaders openly discuss these topics can offer members a safe and loving outlet for helping people understand and take action about their mental health.

What faith leaders have to do with this

In a 2023 guide published by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, researchers from various fields of scientific study and faith traditions came together to better understand the roles of faith leaders and religious communities in suicide prevention efforts. They named issues of mental health and suicidal ideation as especially important for all faith leaders to be attentive to, especially when working with young people. This guide is geared toward helping youth but can be helpful for congregations overall.

In a 2023 guide published by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, researchers from various fields of scientific study and faith traditions came together to better understand the roles of faith leaders and religious communities in suicide prevention efforts. They named issues of mental health and suicidal ideation as especially important for all faith leaders to be attentive to, especially when working with young people. This guide is geared toward helping youth but can be helpful for congregations overall.

Researchers noted that “some faith communities may present challenges for youth. … There may be religious communities that stigmatize suicide, which may silence youth who are experiencing suicidal thoughts.”

Rates of depression and suicidal ideation seem to be higher in communities that negatively react to diverse identities, such as the LGBTQ community, because these reactions isolate members who are grappling with identity and self-worth.

But they also found faith communities with leaders who welcome conversations about mental health and have a hospitality-based disposition toward all people (regardless of their diverse identities) can be extremely beneficial in suicide prevention efforts, especially for youth.

“Belonging to a faith community can serve as a gateway to healing for youth,” says the guide.

When faith leaders create an environment where it is safe for all members to express themselves, and members know they are loved and supported by those in their faith community, those struggling are more likely to talk to someone else about what’s going on. And that faith community is more likely to offer effective help.

The researchers offered a few concrete ways faith leaders can help prevent suicide and be attentive to suicidal ideation in their communities, and Busch gave BNG some practical advice in line with their recommendations.

Know the common signs of immediate or serious risk

While it can be difficult to know if someone is experiencing suicidal ideation, and there may not be visible warning signs, experts say to look out for these things:

- Discussing or planning suicide

- Hopelessness

- Severe emotional distress

- Worrisome or significant behavioral changes (social isolation, changes in sleep patterns, increased anger or irritability, etc.)

Also, be aware a person’s risk of attempting suicide is impacted based on multiple life factors, such as family history of suicide, previous attempts, living conditions or if the person is part of a racial, ethnic or sexual minority.

Have a protocol in place for how you will respond

When you do identify someone who needs help, it’s beneficial to have a plan for how you will respond. These protocols should be ministry specific.

This might include having a plan for reporting the conversation to other trusted adults who may need to know about the situation, such as parents of a youth group member. You might also consider what relevant local resources your church could partner with in these situations, such as behavioral health clinics, counseling centers or hospitals.

Will Busch

Most importantly, think about how your unique role as a minister can be helpful to someone in this context. Know the different ways you can support someone, and understand when another adult or different type of professional needs to step in.

Busch agreed, telling BNG the first thing he does when the topic of suicide comes up is “acknowledge I am not the one who is equipped for it.”

While church can offer a space for individuals to be vulnerable, the job of a minister in these situations is to navigate a person to other professionals and support systems. And be with them on the journey.

One way he said youth pastors can do this is by helping students have conversations with parents and other trusted adults, walking with them as they discover what it looks like to be vulnerable and ask for help from loved ones.

Talk about mental health at church without judgment

Simply discussing mental health at church can be immensely beneficial in suicide prevention. This destigmatizes the topic and sets the precedent that church is a safe space for members to talk about what’s going on.

“It starts with leading by example,” explained Busch. “Be open about how you re-center yourself in times of distress” and remind your congregation, “mental health is a part of the faith journey.”

It is also helpful to discuss and share educational or crisis support resources regularly. This teaches members that your church takes mental health seriously and destigmatizes the use of these resources. Facilitating mental health education also helps members to better understand issues of mental health and be prepared to respond when they arise.

Busch said this can be done in various ways for unique ministry contexts.

One way to do this is not only having resources on hand, but “vocally acknowledging them regularly.” This reinforces the idea that it’s OK to talk about these things at church.

He also emphasized the positive impact a guest speaker whose vocation centers around mental health could have on educating and informing a congregation about the subject. These professionals can help fill knowledge gaps or answer questions when ministers can’t.

Reach out if you think someone is struggling

If you think someone is showing signs of suicide or suicidal ideation, it’s important to check in directly. Listen to how they’re feeling, and refrain from judging them for the state of their mental health.

“If you think someone is showing signs of suicide or suicidal ideation, it’s important to check in directly.”

If you are worried someone might be close to a suicide attempt, researchers note it is OK to ask direct questions like, “Are you thinking about ending your life?”

While these questions may seem like they have the potential to give someone the idea of attempting suicide, they do not. In reality, they help prevent suicide attempts by showing the person you care enough about them to want to intervene.

When a person knows they are loved and noticed by others in their community, the value of their life is reaffirmed and reinforced.

“Healing cannot be done alone,” Busch told BNG. “Our relationship with Jesus comes to its fullest in community” because it “allows a space of fellowship where you can let your guard down a bit.”

When we see each other fully, we are more likely to notice when something is off.

Be prepared to respond if suicide does happen

In the tragic event a death by suicide does happen in your faith community, it’s important you’ve thought about how your congregation might respond and what support they will need from you as a faith leader. Consider what your tradition believes or teaches about suicide and how you might respond practically, theologically and ministerially.

While different faith communities have diverse beliefs about suicide, researchers urge all faith leaders dealing with a suicide death to approach the situation with care and respect for the deceased, not judgment or skepticism.

This can include discussing the death in neutral terms, avoiding conversations that further stigmatize — or glorify — suicide. Discussing the death honestly and neutrally avoids placing moral guilt or blame for the death on the suicide victim and others they were close with who may worry they could have done something to prevent it. Neutrality helps the community authentically process and grieve what has happened.

“We need to avoid seeing it as a sign of weakness,” Busch urged.

Conversations about a recent suicide death might center memories congregation members have about that person. Ministers might help members consider how to remember their loved one moving forward. “You are made better for having known them and you carry that person with you every day,” he said.

And most importantly, ministers should be intentional about cultivating a clear understanding that all people are loved by God, and by their church, with no restrictions or conditions. Congregation members should be reminded they are inherently loved and valued on a regular basis, whether a suicide has happened in their community or not.

“I am made better because I know you,” Busch regularly reminds his youth.

Mallory Challis

Mallory Challis is a master of divinity student at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. She is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG.

Related articles:

Remembering Robin Williams and wishing we could talk openly about suicide | Opinion by Kim Brewer

‘By the Time You Read This,’ a mother’s quest to tell the rest of her daughter’s story

What will you do with your Daniel scar? | Opinion by Mark Wingfield