In 1997, Mercedes Benz launched an exciting ad campaign in an effort to rebrand themselves as more relevant and fun-loving.

The series of ads was set to the Gene Autry song “Don’t Fence Me In,” and those commercials live rent free in my mind until this day. Mercedes was at the time undergoing a change to its iconic car design — a design that had remained relatively unchanged for decades — and in trying to do something new they, well, tried to do something new and their effort made for an injection of fun into the auto industry, at least the marketing aspect of it.

Today, America is trying to do something new. We are on the precipice of perhaps electing a multi-ethnic woman to the helm of our nation’s highest office. And thus, this election exceeds the usual interesting-ness of any election, because these stakes are higher.

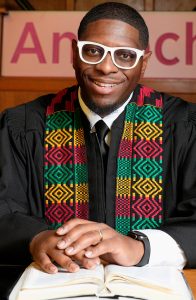

Napoleon Harris

Given America’s shamefully rich history of subjugation, Kamala Harris represents a stark turn from our previous branding. As a nation, we find ourselves struggling to adjust to her as a candidate because historically our nation has held steadfastly to racist and sexist norms. America is urgently like Mercedes trying to launch an all-out effort to rebrand herself. Appropriately, Mercedes’ theme may be the key.

Mercedes begged not to be fenced in. That is essentially a colloquial way of positing the SAT term “intersectionality.” Intersectionality is the means of acknowledging and appreciating the full humanity of another person, a feat we desperately need in this political season.

My brother by another mother, Rabbi Matt Cohen of Temple Emanu-El, and I exercise this in our friendship. We hold different faiths and differing ideas, understandings and therefore sentiments on Israel’s ongoing military conflicts with her neighbors. Although we both want peace, we disagree on the ingredients that constitute that peace. Our disagreement is inevitable because we are informed about the conflict by differing sources. Even stranger, we know that, and yet we remain friends. Our congregations remain in interfaith dialogue, fellowship, service and worship together.

How? It’s because we have not fenced each other in. We view each other through the lens of intersectionality.

“We do not fence each other into small narratives of being only for or against.”

I know Matt, and Matt knows me. We are profoundly — immensely — more than just our stance on this or any one issue and we remain friends because we both recognize that reality. We do not fence each other into small narratives of being only for or against. We realize our stances on any issue are only one part of our multifaceted existence and there are so many more caveats to our being that unite us and keep us in community than there are things to disagree about.

For instance, Matt and I are both liberal front-line soldiers in the ongoing effort for justice and liberation. We are both men of faith, faith leaders, fathers, members of historically oppressed people. We are both music lovers, musicians — he plays guitar and I play crazy from time to time and the fool for my wife. We are both Cleveland natives (die hard Browns fans) who sojourned to the South but returned home with families. In the moments where we disagree, we remember the manifold things that connect us, and they outweigh what we disagree about.

Our friendship is a commitment to understanding, loyalty and transparency. We are committed to dialogue even when, and especially when, we disagree. And we do that because we never fail to see the humanity — the Imago Dei — in each other because it doesn’t fade or rub off just because we disagree on a matter.

Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard advances an idea called “teleological suspension of the ethical,” which is the need to press pause on what otherwise would be considered normative in service to honoring a higher calling. For us, we suspend the societal norm of fencing each other in, to serve the higher calling of love and friendship. We both recognize the residue of God’s love resides in every person — even when a person doesn’t recognize, acknowledge or behave as a person made in the divine mold.

This allows us to see beyond whatever messaging we may be carrying to see the messenger, remembering that social media posts don’t define a person. Matt introduced me to a concept in Judaism about arguments for the sake of heaven — meaning if a conversation, no matter how controversial, isn’t rooted in eternal significance it should fade like an ending song. Instead, we should hold to the God-like good braided into each person, remembering that disagreement or even bad behavior doesn’t dilute or destroy the divine image in each of us.

“Social media posts don’t define a person.”

This is how/why we forgive and avoid myopically fencing each other into just a stance on an issue to ultimately remain friends.

If America is to live up to her full potential as an ideal community where the idea of inclusive excellence is championed, we will need to learn, as Matt and I have, to avoid fencing each other in. This is the only way to truly see, celebrate and embrace the totality of each other as human beings.

There is another tradition our faiths share. In Christianity, we celebrate Palm Sunday as the inauguration of Jesus’ Passion week, and our Palm Sunday correlates with the Jewish Holy Festival of Sukkot, which commemorates God’s faithfulness as the Hebrew people sojourned as pilgrims in the wilderness. In Sukkot there is a tradition called the “four species” or ara’ah minim, also called the lulav and etrog. In both Sukkot and Palm Sunday, palm branches are waved vigorously in celebration. In Sukkot, however, more than palms are waved — three additional types of plants are held together and waved alongside the palm branches.

This celebratory gesture is done in celebration of harvest, and it is a lesson in inclusive excellence. Moreover, it suggests that in order to truly celebrate we need diversity. By not fencing each other in and celebrating the multifaceted nature of each other, we truly commemorate the bountiful harvest laden in the whole of humanity.

Let’s not fence each other into political talking points, countries of origin and stereotypes, because we are so much more than the lies told in misleading political ads, the narrow ideas offered in our nauseating political theater and the silos social media algorithms and entertainment news stations have relegated and sequestered us to. By embracing the whole of our existence and seeing each other in our divinely given totality, we can inject a greater sense of civility into our society, open the line for communication and embrace the understanding and transformation that comes through community when we decide to see each other and not “fence in” each other.

Napoleon Harris serves as pastor of Antioch Baptist Church in Cleveland, Ohio.