Tony Campolo was the first to wake me up to a faith outside of myself.

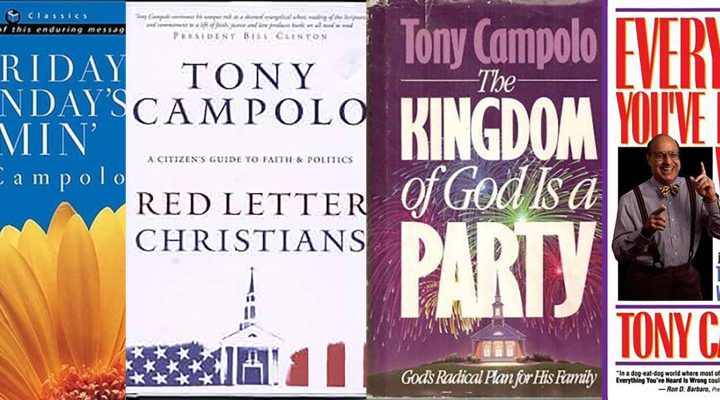

I started college in the late 1990s, full of passion for Jesus and for telling other people about him too. Eager to live out this embodiment of heart, mind and soul, I joined a Christian mail-order book club — the kind that sent you a couple of books every month for the low, low price of a $9.99, plus shipping and handling.

I didn’t have a lot of money, but I did have a lot of zeal and drive. When my peers sent in checks for questionable CDs my pastor would probably want me to burn, I handed over my pennies to a growing collection of Jesus books.

It was here, in these books, that I met Tony Campolo. But it was also here that my pious morality and self-righteousness first got knocked to the ground — for it was none other than Campolo himself who opened my eyes to an embodying kind of a faith that wasn’t so much about a God who lived within me but about the Christ who inspired real and true change in the world.

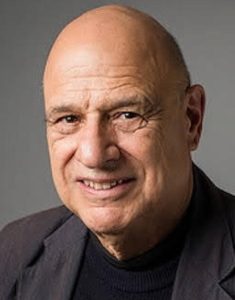

A prolific speaker on college campuses around the world, the American Baptist minister and social justice preacher wasn’t afraid to shake up young people such as myself.

In the early to mid-1980s, Campolo often began addressing college audiences with the following opening lines:

I have three things I’d like to say today. First, while you were sleeping last night, 30,000 kids died of starvation or diseases related to malnutrition. Second, most of you don’t give a shit. What’s worse is that you’re more upset with the fact that I said “shit” than the fact that 30,000 kids died last night.

I wouldn’t meet the dewy-eyed, joy-filled man for another decade and a half, but the same sentiment rang through in the books by him I came to devour. Because it was Campolo who showed me Christianity isn’t just about getting that lucky, golden ticket to heaven. Instead, faith is about looking beyond ourselves. Faith is about doing and being as Jesus showed us to be, which also means faith is about addressing social problems like racism and poverty.

For a cradle American Baptist such as myself, I saw how many of his beliefs about the Social Gospel stemmed from his experience as the child of immigrants and from how a Baptist church in South Philadelphia tangibly cared for his family when they needed it most.

“It’s not about getting a ticket to heaven; it’s about becoming an instrument of God to transform this world.”

In a 2016 interview with High Profiles, Campolo told the following story:

My father couldn’t find a job and they were totally impoverished, and a Baptist mission in South Philadelphia reached out to them, got my father a job, got them a place to stay, put their feet on solid ground and really saved them from despair and destitution. People often ask me: “Where did you get your social consciousness? Where did you get your commitment to the poor, before it was ever fashionable?” My mother and father saw in the way they were treated by a group of Baptists that this is what Christianity is about. It’s not about getting a ticket to heaven; it’s about becoming an instrument of God to transform this world.

When I reflect on this paragraph, my mind fills with images of all the different ways a person can be an instrument of God, a human capable of transforming the world. What does this mean for the Baptists and the Episcopalians and all the other branches of Christianity that fall under the guise of loving God and loving people? How might Christians lead the way in caring not only about hearts and souls, but also about the many facets of what it means to be human in a messy, broken world?

If Tony were still here, I imagine he’d simply offer a smile and a nod to my questions. “Yes,” he’d say. “The Jesus of yesterday is the same as the Jesus of today. He’s a man of radical grace and of an explosive, heart-thumping kind of forgiveness.” And then, with a twinkle in his eyes, he’d throw the question back to me: “So, what do you think loving the poor and fighting against racism means in your neighborhood?”

If our conversation continued, he’d likely add in another sentence or two: “Jesus never says to the poor: ‘Come find the church,’ but he says to those of us in the church: ‘Go into the world and find the poor, hungry, homeless, imprisoned.’”

To this I would nod in agreement, his words an exhortation that would rumble around in the back of my mind for days.

As the years went by, I wouldn’t always agree with Campolo. Even though he changed his mind, to a fair extent, around issues of human sexuality, he continued to hold a rather conservative viewpoint. At certain times in my life, when the programmatics of following Jesus felt more like a bedazzled spectacle for holiness and less like a simple invitation into embracing the presence of the divine, I couldn’t always swallow the dynamics he had to offer.

But as time went by, I would return to one of the first books that came in the mail. I would say hello, once again, to a leader who taught me to look beyond myself and toward my neighbor — who worked tirelessly to point people to Jesus and make real my faith by caring for the poor.

I would nod to the skies, grateful for the man who first woke up my faith.

Cara Meredith was raised in the American Baptist Churches in the USA but currently worships as an Episcopalian. She is a freelance author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her books include The Color of Life and Church Camp: Bad Skits, Cry Night, and How White Evangelicalism Betrayed a Generation.

Related articles:

Sunday came for Tony Campolo | Analysis by Steve Rabey

Campolo says ‘Red Letter Revival’ seeks to convert evangelicals to social activism

Progressive faith leaders call for renewed attention to 8 principles of faith and democracy