One simple way churches could proclaim truth in an era of Trumpian disinformation is to speak plainly about the importance of vaccines.

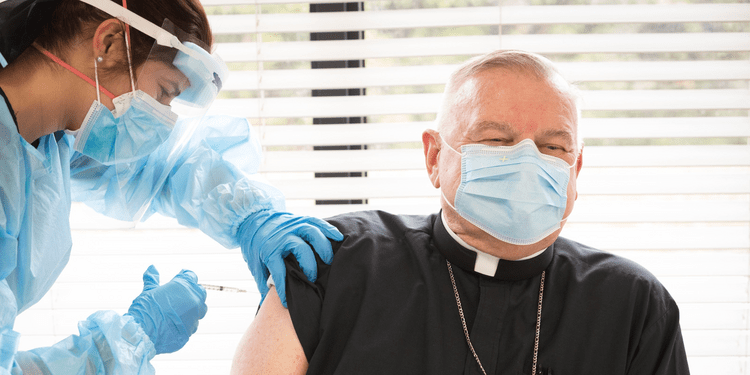

At the height of the COVID pandemic, as many Americans were resistant to what they considered an untested new vaccine, it was faith communities that convinced vulnerable people it was OK to trust medical science.

Now, with the nomination of vaccine denier Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to head the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, faith leaders are needed once again to speak truth to power. This is all about something churches do well: building community.

For vaccinations to be effective requires a “herd” mentality — specifically, “herd immunity.” In other words, vaccines are most effective when the largest number of people in the community are vaccinated. This is the very definition of loving your neighbor as yourself.

You may recall that the religious leaders most vocally opposing COVID precautions and vaccinations were those who discounted this essential teaching of Jesus. They were more concerned with their rights than with the health of the community.

Yet Christianity is all about community, not selfish independence. It is about gathering for worship, gathering for service, gathering on mission, gathering in love. Love cares for others more than self.

Christian history and health care

And there’s a long history of the Christian church being trailblazers on health care. Think of all the hospitals you know that were started by Catholics or Baptists or Presbyterians or Methodists.

Writing in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, Harold Koenig explains: “A quick tour of history reveals that the Christian church built and staffed the first hospitals during the Middle Ages, the entire nursing profession emerged from religious orders, and most physicians during early American Colonial times were also ministers. In the mid-20th century, church-related hospitals in the United States cared for more than a quarter of all hospitalized patients, and Catholic hospitals alone saw nearly 16 million patients per year.”

Outside America, faith communities often play an even larger role in influencing health care — both for good and for ill.

In 2021, a hospital in Uganda received 5,000 COVID vaccine doses but was only able to administer 400 because of the hesitancy of the population heavily influenced by American evangelicals.

Sadly, in recent times portions of the evangelical church have become hives of anti-vaccination conspiracy sharing. That problem predates COVID but was exacerbated by the pandemic.

The anti-vax movement

A 2023 article in The Lancet explained: “Over the past two decades, anti-vaccine activism in the USA has evolved from a fringe subculture into an increasingly well organized, networked movement with important repercussions for public health. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this evolution and magnified the reach of vaccine misinformation. Anti-vaccine activists, who for many years spoke primarily to niche communities hesitant about childhood vaccinations, have used traditional and social media to amplify vaccine-related mistruths about COVID-19 vaccines while also targeting historically marginalized racial and ethnic communities.”

“Conspiracy theories about COVID took a torch to the smoldering fire.”

What was brewing before COVID was a merger of religious and political conservatism soaked in libertarian and evangelical mistrust of science. Conspiracy theories about COVID took a torch to the smoldering fire.

KFF reports: “Routine vaccination rates for kindergarten children continue to decline in the U.S., while exemptions from school vaccination requirements, particularly non-medical exemptions, have increased. These trends began with the COVID-19 pandemic and appear to be related to increasing vaccine hesitancy, fueled in part by vaccine misinformation. Furthermore, public opinion on vaccine requirements has become increasingly partisan.”

For example: “The share of kindergarten children with an exemption from one or more required vaccinations increased. The share of children claiming an exemption from one or more vaccinations rose from 2.5% in the 2019-2020 school year to 3.3% in the 2023-2024 school year, the highest national exemption rate to date.”

Enter RFK Jr.

And now Trump wants to put RFK Jr. in charge of public health. A man whose views on vaccines are so terribly misguided they are a danger to public health.

Kennedy’s nomination validates and enshrines public mistrust of government health programs, Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee to be the next Health and Human Services Secretary, arrives for a meeting with Sen. John Cornyn on Capitol Hill January 9. (Photo by ALLISON ROBBERT/AFP via Getty Images)

“The notion that he’d even be considered for that position makes people think he knows what he’s talking about,” Offit said. “He appeals to lessened trust, the idea that ‘There are things you don’t see, data they don’t present, that I’m going to find out so you can really make an informed decision.'”

In other words, conspiracy theories.

During a November 2019 measles epidemic that killed 80 children in Samoa, Kennedy wrote to the country’s prime minister falsely claiming the measles vaccine was causing the deaths. The results were devastating.

This recently prompted Josh Green, a physician who is the current governor of Hawaii, to write an op-ed in The New York Times: “When vaccination rates fall, preventable diseases can regain a foothold and pose a new danger. And that’s precisely what happened in Samoa, after misinformation spread by anti-vaccine activists eroded trust in vaccines and led to the 2019 outbreak. Thousands of preventable cases of measles sprang up, leading to the deaths of 83 people, mostly children. One of the most prominent voices behind the anti-vaccine campaign was Robert F. Kennedy Jr.”

An ’older’ pediatrician’s view

Rhonda Walton is a pediatrician friend of mine who worked in public health in Texas most of her career. Her husband, also a physician, has been equally influential in advancing public health in North Texas.

“As an ‘older’ pediatrician, I’ve seen how vaccines (or their avoidance) can impact children’s lives in profound ways,” Rhonda Walton told me. “I’ve taken care of infants who died or had severe brain damage or deafness from Hemophilus meningitis. Most younger pediatricians have never seen a case of Hemophilus, because the Hemophilus vaccine came out in the 1980s. I’ve cared for newborns struggling to breathe in the ICU because they caught Pertussis from an unvaccinated sibling. Vaccines allow us to prevent avoidable suffering, and this is a huge blessing that should not be taken for granted.

“I’ve cared for newborns struggling to breathe in the ICU because they caught Pertussis from an unvaccinated sibling.”

“I understand that parents might be apprehensive about vaccinating their kids, especially given the overwhelming amount of conflicting information on the internet. No vaccine is 100% risk-free, but I firmly believe the risk of getting standard vaccines is far, far less than the risk of getting the diseases they prevent.”

Her view is the overwhelming consensus of the medical community — you know, those folks who have pledged to “first, do no harm.”

I asked Walton if she believes the faith community has played any role in advancing vaccines in the past.

She replied: “In my experience, faith communities have not participated much in promoting vaccines, but I have taken part in discussions at a church that had a large, vocal homeschooling group that unfortunately convinced families not to vaccinate. We tried to persuade these families to, at the very least, refrain from participation in activities where their older unvaccinated children might expose young infants who were particularly at risk. It was a difficult discussion, as it seemed these parents were unreasonably concerned about the risk vaccines posed to their children but not terribly concerned about the risks their children might pose to others.”

Remember that bit about “love your neighbor”?

Vaccinations should be a concern to churches because they frequently gather children in close spaces. That means both the children and the teachers in those spaces ought to be vaccinated.

As 8-year-old girl receives a polio vaccine, she watches a closed circuit television broadcast (showing Dr Jonas Salk as he inoculates a boy) of a training telecast for physicians and scientists, New York, New York, April 12, 1955. (Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

“I suspect the unfortunate politicization of the vaccine topic might make some faith communities less likely to engage in influencing their congregants or even to require immunizations for those who work in or attend child care situations in the church,” she said. “This is an extremely relevant topic for faith communities as they balance the desire to be welcoming to everyone while being attentive to the safety of physically vulnerable people in the community.”

Vaccinations should not be an ala carte option on the menu, the pediatrician explained.

“Even though vaccines prevent serious illnesses or decrease the severity of illness, no vaccine is 100% effective. That means if vaccine rates decrease, even those children who are completely vaccinated are more at risk.”

And, once again, churches could do more good than harm if they would talk about and promote vaccination.

“Many people do look to their faith communities for advice and support in caring for their children and other family members,” Walton said. “The church should be about truth-telling, as much as possible, about any topic that effects congregants. The very nature of ‘community,’ especially a community of Christ-followers, implies a practice of looking out for each other and considering the welfare of fellow members and the broader community.

“Except in cases of medical contraindications, an anti-vax stance is not only based on misinformation but also disregards any concern for the safety of other community members.”

Related articles:

How John MacArthur loves the Bible but not his neighbor | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Vaccine hesitancy is not a matter of doctrine, but for some it remains a matter of faith | Analysis by Mallory Challis

Faith leaders are key to reaching herd immunity in U.S., researchers say

Florida surgeon general spreads more doubts about COVID vaccines