There is something wrong with 2016.

There is something wrong with 2016.

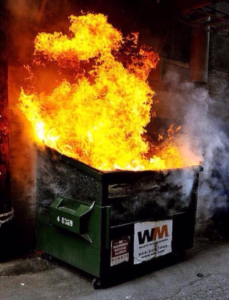

That may be the most self-evident and non-controversial statement to come up in your Facebook newsfeed in quite a while. In fact, it has become an almost universally acknowledged truth. So many of us would rather do without 2016 that it has spawned memes. These Internet icons of our current season have called 2016 a veritable “dumpster fire” of a year. 2016 is a burning pile of garbage you are not sure what to do with because there is so much rubbish involved that you do not know which conventional fire extinguishing technique will resolve the situation and which would just ignite the whole city block. If that image did not connect, consider this one, more elegant in its simplicity: “2016, go home, you’re drunk.”

2016 is not close to over and for many of us it has been a pretty terrible year. Pick your poison: mass shootings, police brutality, hate crimes, humanitarian crises, terrorist attacks or even presidential elections. But 2016 has been uniquely terrible for me and mine. I will not divulge all the gory details, but let’s just say the litany of tragedies followed by colossal disappointments assisted by prolonged reasons for sadness have been far from a walk in the park. I also do not need to supply you all the details because some of you know all too well what I mean because 2016 has not been kind to you either. 2016 has swung for the fences when it comes to routinized sadness in your life. You do not need to divulge all the gory details. Trust me, I know exactly what you mean.

2016 is not close to over and for many of us it has been a pretty terrible year. Pick your poison: mass shootings, police brutality, hate crimes, humanitarian crises, terrorist attacks or even presidential elections. But 2016 has been uniquely terrible for me and mine. I will not divulge all the gory details, but let’s just say the litany of tragedies followed by colossal disappointments assisted by prolonged reasons for sadness have been far from a walk in the park. I also do not need to supply you all the details because some of you know all too well what I mean because 2016 has not been kind to you either. 2016 has swung for the fences when it comes to routinized sadness in your life. You do not need to divulge all the gory details. Trust me, I know exactly what you mean.

If your 2016 has been anything like mine, you have heard a lot of things that have started to ring as hollow as a politician’s promise. People tell you, “God is in control.” Folks say, “God has a plan. This is all part of his plan.” They try, “God is going to use it for good.” Or they return to the tried and true, “Everything happens for a reason.” I do not know what 2016 has been for you. Maybe you are unemployed and people keep telling you that God has the perfect job out there for you. Maybe you are single and just feeling a little lonelier this year than most, and people keep telling you that God has “the one” out there for you. Maybe you have been trying to have a child to no avail, and people keep telling you that God will bring some good out of this pain. Maybe you lost a loved one and people keep telling you that God simply needed another angel. Maybe you are sick and people keep saying God has a plan for your disease.

Chances are, if you have heard any of these truisms (and there may be bits of truth in some of them) and they had any power for you before, 2016 may have rendered them bankrupt. You may be having the kind of year where clichés stop making sense. You may have had the urge to smack someone across the head when they say these things. You may want to grab them by the collar and shake them if they say it one more time. The trite aphorisms that keep Hallmark in business may now be the object of your ire. Or maybe this is just a cathartic exercise for this pastor, but I do not think that is the case. I know I am not the only one, and I know you are not alone in your pain.

Our pain and our suffering — and even these clichés — can keep some of us up at night wondering about God’s faithfulness. That is what all these well-meaning sayings are trying to talk about. They are wrestling (albeit poorly) with a core biblical teaching: God is faithful. But how do we talk about God’s faithfulness when we or someone we love is in a great deal of pain?

Part of the problem is we try to be too specific. We try to know too much. We think we can name the inner-workings of God’s sovereignty and that will at least make meaning of the suffering we see. But these propositions allow us to avoid uncomfortable things like blame, responsibility, presence, and solidarity by hanging our hats on the fact that “everything happens for a reason.” Most attempts to answer our suffering (what theologians call “theodicy”) is really an attempt to “solve” suffering with some understanding of God’s mechanisms. We try to look under the Trinitarian hood, so to speak, and tease out how it works. Then we do not have to deal with the suffering of others or ourselves.

A dear friend and mentor of mine who has endured more than his fair share of suffering once told me that in all his reading on theodicy, he had finally come to a conclusion. All attempts at theodicy were attempts to “save the phenomena.” That is a phrase historians of science may recognize. They often use it to describe the behavior of astronomy when it engaged in herculean intellectual gymnastics rather than confronting the truth that the earth revolved around the sun instead of the other way around. The scientists of that day invented elaborate theories of planetary motion to avoid the prospect of a heliocentric universe. They wanted to “save the phenomenon” of a geocentric universe.

We often try to say more than we know about God.

We try to save the particular phenomenon of a mechanistic God we can control – or at least one we can fairly well predict. We try to save the picture of a God who responds to the levers we pull or the puppet strings we tug. We do not always have bad motivations for doing that, let’s be clear. No, sometimes that is the only image of God that we believe will get us through our pain. But that is not necessarily the Christian God.

The God we encounter in the Bible is not a God we can grasp in this way. We cannot take ahold of this God and master the divine. This God is unpredictable and under no one’s control. This God is in burning bushes, whispers, whirlwinds, pillars of fire and smoke, and even in a manger. This is not a mechanistic God we can reliably predict or control. For all we say we know about what God does and what God will do, how God works or what God controls, the Bible chooses a different path most of the time. Instead of explaining what or how God controls, Scripture tells us where God is.

Where we strive for certainty and predictability, God always seems to settle on presence. Christian talk about God is not so much about what God controls, but about where God is. That is not to say we do not know anything about the God we worship. Far from it. Instead, it is to admit with humility, as many great Christians have confessed, “If you can understand it, it’s not God.” God does not assure us with knowledge of some divine machinery but God reassured us with presence.

That’s part of what this whole thing with Jesus is all about.

In Jesus, we are reassured of God’s presence with us. Jesus was fully God but also fully human, a body vulnerable like ours. Jesus, a body vulnerable, is wracked with grief, sickness, pain, sadness, despair, and loss. And there is no God hiding behind Jesus, completely different from Christ. There is not some God out there that contradicts the God we know in Jesus. God knows intimately and deeply our pain and our suffering. God knows it in painful flesh. And this God is still God to this day in the midst of our dark times.

That is the God we know. As Christians, we do not confess knowledge of the inner-workings of the breadth and depth of the divine and God’s intentions, involvement or motivations for every little thing. Instead, as Christians, we confess faith in a God who is with us.

We can only adequately speak, then, to the faithfulness of God after the fact. The minute we presume to know what faithfulness must look like, we have stopped talking about God and begun talking about something else. The minute we believe that we can sort out divine causes, culpabilities or motivations (especially for our suffering), we stop talking about God. The truth is, we will not know exactly what to call faithfulness until long after the fact, sometimes impossibly late.

Instead of talking about God that way, we need to talk about the God we know. The God with us. We do not always know what God has in store for us next. We do not always know why things happen. We do not always know what faithfulness looks like. But we know that God is somewhere. We know that God is all over this messed up world being God. We can trust that. We can trust that God is present and working somewhere in this place – even when we cannot definitely say where.

There is a consequence to that belief. That belief demands divine solidarity with the suffering. That could mean helping someone find a job instead of telling them God has one out there for them. That could mean spending some quality time with someone feeling lonely instead of pawning them off to be fabled “one” God has for them. That could mean providing space of grief for those struggling with fertility instead of telling them it is all part of God’s plan. That could mean staying and weeping with someone who lost a loved one long after the funeral instead of mumbling something about angels. That could mean being someone who does more than pity the sick, but still recognizes them as the fully human friend they never stopped being.

But that is a word for the helper. Here is a word for the afflicted from one of your own: God has not abandoned you. You are not alone. We may not know the why, the how, the when or even the what, but we know God. And God is with you, and so am I.