Residual shock and shivers of insecurity still reverberate from Timothy McVeigh’s devastating assault on the nation’s psyche when he bombed the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City April 19, 1995, killing 168 people and injuring at least 680 others.

Six years before the terrorist attacks of 9/11, it was at the time the most destructive assault on American soil since Pearl Harbor in 1941.

First responders poured into the city to comb the rubble for survivors, even as dust and ash drifted skyward from the hulking remains of a building that swayed ominously in the Oklahoma wind. But, after the first day, they found none.

In later days, search dogs became despondent and distracted as they sniffed through debris because they were finding no signs of life. Fireman hid in the wreckage to give the dogs “survivors” to find. Some first responders later took their own lives, seeded by the despair of that scene.

A solemn anniversary

April 19 marks the 25th anniversary of what’s now known as “The Oklahoma City bombing,” and a solemn memorial marks the area where the Murrah Building stood. The acrid smell of diesel fuel and fertilizer – the elements of McVeigh’s powerful truck bomb – has been washed into the soil, but many lives will never shed the clinging odor.

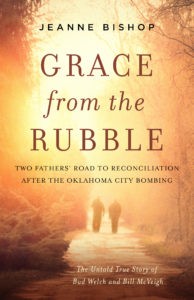

Yet, also from the rubble, rises a story of grace and reconciliation that many may find difficult to comprehend. It is detailed in a book to be released April 14 by Zondervan written by author, lawyer and criminal justice advocate Jeanne Bishop – herself an Oklahoma City native – titled Grace from the Rubble.

Jeanne Bishop (Photo/Scott Friesen)

In it, Bishop, now a public defender in Skokie, Illinois, describes how Bud Welch, the father of one victim, strides through the dust devil of howling voices calling for revenge to advocate instead for peace, and even forgiveness. Bishop, whose own pregnant sister and her sister’s husband were brutally murdered in Winnetka, Illinois, in 1990, describes how Welch’s stand eventually brought him together with the perpetrator’s father, Bill McVeigh.

Distinctly different, yet similar in many ways, the pair might have been good friends, had they not lived half a nation apart. Both are Catholic, both love the land and their children, and both are active in community groups. And of course, both were deeply affected by the tragedy perpetrated by the child of one that killed the child of the other.

Welch’s daughter, Julie, a tiny fireball and language interpreter, was on the cusp of marriage when she walked to the front of the Murrah Building that morning, 90 seconds before the explosion, to translate for a Spanish-speaking man who was applying for a Social Security card. Those who remained in the storeroom she’d just left survived.

Welch was devastated. But with a faith unimaginable to many, he refused to let his pain devolve into the searing agony of hate.

During the past 25 years, he has become an international advocate against the death penalty – even for the perpetrator responsible for his daughter’s death.

An amazing grace

Grace washes over the entire story when Bud Welch meets Bill McVeigh, the terrorist’s father. Two dads, each of whom has lost a child, find friendship. While almost all the other victims’ families – and most of the nation – clamored for the death of Timothy McVeigh, Welch consistently advocated against his execution.

It made no sense to Welch, he said, to drag McVeigh “from his cage” to be executed to satisfy the blood lust of victims and a victim nation. McVeigh’s death would do nothing to restore wholeness to those who grieved. And it would just fuel the cycle of revenge.

Welch embraced the platform his tragedy provided and spoke to international media until his voice was raw. He was adamant that no part of killing another son was going to “bring closure” or heal him in any way.

Bill McVeigh chose a completely different path to deal with the blood stain his son spread on the family. He granted no interviews and declined anything that would put his son’s name in the public arena, such as a name on a veteran’s plaque from his community or even a grave site.

Bill McVeigh lived all but the two years he was in the military in his small New York town. Everybody knows him. He’s in church, in bowling and poker leagues. He golfs and is active in the VFW and volunteer fire company. He’s connected to the community and to many of its families. He’s as foundational to the community as asphalt is to a road.

Welch at first worked hard to try to meet Timothy McVeigh in prison. He wanted to talk to him, to encourage him and tell him that he was not in favor of McVeigh being executed. That meeting never happened. However, with the help of Roman Catholic sister Helen Prejean – a leading American advocate for abolition of the death penalty – he was connected instead to Bill McVeigh.

Bill’s son, Timothy, declined to press the appeals typically pursued by persons sentenced to death, and he was executed June 11, 2001, a relatively short six years after his crime.

How two men ‘responded to evil’

Twenty-one percent of America’s population wasn’t born on April 19, 1995. The rest of the country remembers how the bombing shattered the nation’s psyche and made everyone feel vulnerable.

Bishop lived in Oklahoma City from age 10 through college. In an interview in her century-old home in Winnetka, Illinois, just blocks from where her sister died, she recalls how the city’s schools and churches shaped her. From her pastor at First Presbyterian Church she learned that “love is something you do” and that “forgiveness is a muscle you must exercise.”

“I don’t want people to spend the 25th anniversary of the bombing talking about Timothy McVeigh,” she says. “I want people to be talking about these men and how they responded to evil.”

“The poisonous anti-government, white supremacist, downtrodden male, ‘women-taking-the-jobs-men-should-have’ and whole poisonous gun culture just infected him like a plague.”

Bishop didn’t know the elder McVeigh before starting her book. She only got to meet him because Welch vouched for her. She learned McVeigh was horrified by what his son did. To this day, he doesn’t understand it and can’t explain it. He is deeply sorrowful for all the people who lost lives, loved ones, limbs, eyesight and sense of security.

But he has never disowned his son. He’s not changed his name or declared that Timothy “is no son of mine.”

“I’ll never understand what he did, but I’ll always love him,” Bill said of his son who was never in trouble a single day before he turned America inside out.

Just an ‘ordinary’ kid

Timothy McVeigh was just an ordinary, nondescript, unnoticed kid.

“This is what makes him so scary,” Bishop explains. “He was so ordinary, there could be a thousand Timothy McVeighs out there. What turns a kid like this into someone who becomes Timothy McVeigh?”

She is convinced that the “poisonous anti-government, white supremacist, downtrodden male, ‘women-taking-the-jobs-men-should-have’ and whole poisonous gun culture just infected him like a plague.”

Bishop loves the biblical story in John 8 where the woman caught in adultery was brought to Jesus for judgment. Adultery was a capital offense in Jewish law. “Jesus didn’t say she didn’t deserve to die,” Bishop says. “He said we didn’t deserve to kill her.” Jesus stopped an execution based not on her sin, but on his mercy.

A flawed criminal justice system

“As someone who works in the criminal justice system every day and who knows how flawed it is because it’s run by human beings, I really take that to heart,” she says. Bishop left private law practice to become a public defender in 1990 after her sister was killed. (Bishop, the subject of a profile published by Baptist News Global in 2016, tells her own remarkable story of forgiveness in her first book, Change of Heart.)

“I wanted to write about how we respond to evil,” she says, naming the tragedies of Newtown, Parkland, Tree of Life, Mother Emmanuel, El Paso, Las Vegas – all carried out by angry, young white men. “We have to learn how to respond to that other than with more evil.”

Ironically, Timothy McVeigh wanted to die, rather than spend life in prison. Consequently, the warden kept him on suicide watch. “They didn’t want him to commit suicide, so WE could kill him,” Bishop says, shaking her head.

“We didn’t punish Timothy McVeigh; we gave him what he wanted,” she declares. His death and the death penalty in general are “no deterrents,” she said, noting that the 9/11 attack came just three months after McVeigh’s execution. “The terrorists were not deterred by the threat of death. They had baked it into their plan.

“If the death penalty is no deterrence and no punishment, then why do it? It’s for revenge. And revenge doesn’t work.”

Postponed anniversary observance

A significant 25th anniversary observance in Oklahoma City was scheduled, but the global coronavirus has postponed it indefinitely. That includes promotional events for Grace from the Rubble, which of course is disappointing for Bishop. She still hopes “people looking for a good read will curl up with” her new book.

Welch doesn’t go to memorial services anymore. His way of honoring the fallen is the work he does in memory of his daughter.

Bill McVeigh wouldn’t have been there anyway. He’s never been to the Oklahoma capital. He feels he has no right. He wants no one, ever, to feel pain at the mention of the McVeigh name.

Bishop has been a public defender for 30 years, but at age 60 has no thought of retiring. With a son in the Naval Academy, a 16-year-old at home and a mother who worked until age 81, she says she is “the opposite of burned out. I’m fired up, just to see so much in the justice system that needs to be changed. The pendulum is starting to swing.”

“If the death penalty is no deterrence and no punishment, then why do it? It’s for revenge. And revenge doesn’t work.”

She’s knows how important it is to establish trust and relationship with her clients, all of whom are prisoners who could not afford representation “by a real lawyer.”

She’s learned no longer to ask them “What did you do?” Instead, she asks, “What happened to you and how did you get here?”

Those are questions Bill McVeigh still wonders about his son.

Fathers’ grief a timeless story

Bishop says the story of two fathers’ grief for their children is timeless. “It’s the grief of fathers who love their children and their determination to redeem them.”

Her Lenten exercise this year was to think each day of four people who died that April day in Oklahoma City, read about them, meditate on their lives and the people who loved them, and remind herself she has not one minute to waste in this life.

She often thinks of Tom Mauser, whose son died in the Columbine High School shooting in Littleton, Colorado, 21 years ago this month. On that awful and unforgettable day, he waited with other anxious, prayerful, tearful parents at a site away from the school. Children would be transported to the site by school bus. Each time a bus arrived, its occupants would step into the arms of joyful parents.

The ritual was repeated, with more buses and more hugs until there were no more buses, and the parents who remained realized their children were probably among the dead.

“I’m fired up, just to see so much in the justice system that needs to be changed. The pendulum is starting to swing.”

Bishop recalls “Tom saying later that we’re all in that room every day. We don’t know whether our bus will be coming for us or not.”

In downtown Oklahoma City, an American elm somehow survived the 1995 bombing and the subsequent treading of people and machines over the area during the recovery. The Survivor Tree is a significant part of any memorial observance there, and one of the most meaningful elements is the distribution of saplings that have sprouted from the tree.

The symbolism of hope and survival offered by those saplings is obvious. Twenty-five years after the horrendous tragedy, hundreds of American elms now grow around the nation, rooted from the Survivor Tree.

Bishop hopes to take one of the saplings to Bill McVeigh someday and help him plant it in his garden.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the latest installment in BNG’s Storytelling Journalism Initiative launched in 2017. The project has included in-depth reporting and analysis on issues of racial and economic justice, rural poverty, music and faith, immigration and other issues.