Jews are urged to flee Russia as the persecution of religious minorities in that country increasingly matches the oppression of Ukrainian faith groups, an exiled rabbi said during a webinar hosted by the U.S. Commission on Religious Liberty.

“This new situation for Jews in Russia is becoming more and more dangerous,” said Pinchas Goldschmidt, chief rabbi and president of the Conference of European Rabbis and the exiled chief rabbi of Moscow.

Approximately 50,000 Jews have emigrated from Russia to Israel since Vladimir Putin’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and about 30,000 more have left for numerous European and Middle Eastern countries, Goldschmidt said during USCIRF’s March 15 event titled “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: Implications for Religious freedom.”

Goldschmidt said he decided to leave Russia so he could continue to monitor and criticize the Kremlin’s increasing persecution of Jews — an activity that is now illegal in that country.

“We are worried about the state of the Jewish community there. Not everyone can leave,” he said. “We can definitely call the Jewish community of Russia today a community in distress.”

Ukraine invasion

USCIRF arranged the virtual gathering to illustrate the reality that minority religious groups have become targets of repression in Russia. Joining Goldschmidt on the panel were global human rights experts, a U.S. senator, a Danish Jehovah’s Witness leader formerly imprisoned in Russia and an anonymous Crimean Tartar activist.

Nury Turkel

USCIRF Chairman Nury Turkel opened with a reminder that Russia’s ongoing legal and military actions against religious minorities in Ukraine predate the 2022 invasion.

“In the parts of Ukraine occupied and controlled by Russian forces since 2014, we have seen Russia effectively export the religious freedom violations it has long committed within its own borders, including banning religious groups as extremists, issuing lengthy prison sentences for peaceful religious activities and prohibiting religious literature,” Turkel said.

Since the Crimean annexation, Russia also has brutally oppressed the region’s Muslim Tartar population through physical attacks and long prison sentences related to religious identity and for objecting to the occupation, he added. “And Russia has doubled down on the repression of its own citizens’ religious freedom and other related human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

Disinformation campaign

Putin’s attack on Russian and Ukrainian religious liberty also has been marked by a disinformation campaign designed to convince the international community that the invasion of Ukraine was just and necessary, said USCIRF Vice Chairman Abraham Cooper.

“The Russian government has repeatedly turned to shocking examples of antisemitic rhetoric and Holocaust distortion as part of that effort.”

“Disturbingly, the Russian government has repeatedly turned to shocking examples of antisemitic rhetoric and Holocaust distortion as part of that effort. When President Putin announced his country’s invasion of Ukraine, he falsely claimed that the goal of his so-called, ‘special military operation’ was to ‘demilitarize and de-Nazify’ Ukraine. We know there is no such justification for Russia’s aggression against its neighbor and that such claims against Ukraine have no basis in reality.”

Abraham Cooper

Yet the claims have persisted and evolved into labeling Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as a Nazi despite the fact he lost family members in the Holocaust and his father was Jewish. When challenged, Putin “replied with more hateful rhetoric blaming the Jewish people for the Holocaust,” Cooper said.

“One Russian official went so far as to call for the ‘de-Satanization of Ukraine,’ referring to several religious groups like the Church of Scientology and the Chabad Lubavitch (Jewish) movement as ‘neo-Pagan cults’ promoted by the Ukrainian government to force its citizens to abandon ‘traditional religious values.’ This should be understood as nothing less than the elimination of Ukraine’s flourishing religious diversity,” Cooper declared.

Putin’s goals

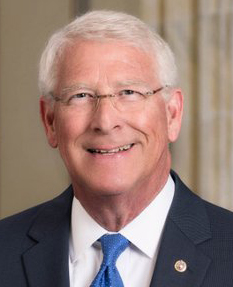

Putin’s actions indicate he wants to return Russia to its totalitarian past, said U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi.

“The Kremlin’s renewed, all-out assault on Ukraine reveals Putin’s goals. He wants to go back to the old Soviet empire by any means necessary,” Wicker said. “Domestically, President Putin has leveraged the religious nationalism of the Russian people for his own cause.”

“The patriarch has urged Russians to side with the persecutor over the persecuted.”

Roger Wicker

To garner public support, the operation in Ukraine has been framed as a religious war with the backing of Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill, Wicker added. “The patriarch has urged Russians to side with the persecutor over the persecuted. No authentic theologian would endorse such flagrant violations of human rights. In fact, it is appropriate for the United States and European partners to consider whether Kirill himself should face sanctions.”

But the Soviet-style tactics are also being applied at home through “several draconian Russian laws” that violate “the most basic fundamentals of religious freedom,” said Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, a USCIRF commissioner.

The statutes include a requirement that all non-Orthodox religious groups register with the government and agree to being monitored by law enforcement. Others place bans on “preaching, praying, disseminating religious materials, and answering questions about religion outside of officially designated sites. Russian courts have also increasingly designated religious groups as ‘extremists’ without adequately defining the term, or ‘terrorist’ without providing any evidence of terrorist activities or the promotion of violence,” she said.

Russia also forced the closure of Amnesty International and other human rights organizations with offices in Moscow in April 2022, “making it more difficult to monitor and document freedom of religion or belief and other related human rights violations,” Kleinbaum said.

Rachel Denber

These tactics reflect a fundamental distrust of religious or secular institutions that the government does not control, said Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia division of Human Rights Watch.

“The Kremlin has sought to militarize Russian society and is really seeking to double down in an all-out drive to eradicate public dissent,” Denber added. “Russian public life is unrecognizable as compared to even 18 months ago, when authoritarian autocracy was already deeply entrenched.”

Censorship and detention

The campaign includes strict censorship laws that have “largely eviscerated freedom of expression in Russia” by criminalizing “any speech critical of the war or Russian forces’ conduct,” Denber said. “And authorities aggressively push traditional Russian values and demonize culture and ideas they deem at variance with these values. So, if the government can’t control the religious community, the impulse is to deem it a threat to Russian traditional values.”

Dmytro Vovk

In Ukraine, those impulses have resulted in the documented murders of at least 26 religious leaders and the damage or destruction of 500 religious buildings, said Ukrainian Dmytro Vovk, visiting associate professor of law at Cardozo School of Law in New York.

“Many more (Ukrainian) Orthodox, (Byzantine Rite) Catholic and Protestant priests and believers were detained, tortured and subjected to humiliating treatment,” he said. “Many religious properties were captured and used for military or other purposes, such as sniper nests.”

Crimean Tartar testimony

USCIRF Commissioner David Curry read the testimony of a Crimean Tartar activist whose identity was not provided to prevent retribution.

The activist reported that Russia’s campaign of persecution in Ukraine also extends to local culture and identity through the “disappearance of activists or members of their families, intimidation of activists by law enforcement agencies, convictions for bogus crimes, by closing down schools and discouraging the use of the mother tongue.”

Before Russia’s occupation, the Crimea was home to more than 2,200 registered religious organizations. Fewer than 800 remained by January 2016.

“I would like to mention here that some of the religious organizations were registered only after they had agreed to collaborate with the Russian occupying authorities or after the governing bodies of these organizations had been replaced with those favorable to the Russian Federation,” the Tartar activist said.

Dennis Christensen

Dennis Christensen, a Jehovah’s Witness and former religious prisoner of conscience in Russia, predicted human rights violations will continue to intensify because they always do under Putin.

“It began in the year 2007 when Russian authorities made a new law about extremism,” Christensen said. “After that, they began to ban some of our religious literature. The police came sometimes to our meetings and filmed all those who attended, and I could not really understand at that time why were they doing this.”

That gave way to secret police spies producing false evidence that Christensen was engaged in extremist activities. “They told a lot of lies about me, about my religion. They had already made their own decision a long time ago, before this court case began. And I knew that I was to receive six years of prison just for being a Jehovah’s Witness.”

That was in 2017, but conditions were worse by the time he was released from prison in 2022 and deported to Denmark. “Now, they’re not really trying anymore. It’s just if you are belonging to the community of Jehovah’s Witnesses, then you are guilty and then you will go to jail.”

In the few cases where Witnesses have been exonerated, subsequent appeals by authorities have ended in prison sentences, he said. “Unfortunately, this goes on and on and it is getting worse and worse.”

Related articles:

Russia’s attacks on Ukrainian religious sites are war crimes

In survey of religious oppression across the globe, Russia, Afghanistan and China take center stage