This week, a reader of Baptist News Global wrote to columnist Greg Garrett to refute his excellent column on Brittney Griner. I wrote a similar column back in August. Our points were similar: Why is a Baptist university like Baylor so silent on the plight of one of its star athletes held captive by Vladimir Putin?

This reader says we have it all wrong. Baylor’s silence is not because Griner is a Black lesbian athlete, it’s because she’s not a “patriot.” Therefore, she deserves whatever she gets in Russia’s undemocratic system.

The “real reason Christians and non-Christians alike don’t talk about Brittney,” the reader wrote, “has nothing to do with her sexual orientation and everything to do about her lack of appreciation and respect for our country. If and when I ever hear people talking about Brittney, it is always about how she is a non-patriot and an embarrassment to Baylor and everything we stand for. … Brittany or anyone else that chooses to stay in the locker room or take a knee for the Pledge of Allegiance shouldn’t be surprised when few rally around when she finds trouble in another country.”

“If and when I ever hear people talking about Brittney, it is always about how she is a non-patriot and an embarrassment to Baylor and everything we stand for.”

The reader concludes: “We want our country back and God to be our leader! That’s where we are in 2022.”

Confusion about patriotism

There’s confusion among Americans about patriotism. There’s plenty of horn-blowing, drum-banging displays of patriotism, but there’s more to patriotism than emotional display or religious devotion. No wonder Paul Krugman calls superpatriotism by its formal name: “fraud.”

Patriotism should not be confused with braggadocio or even bravery in war. Nor should it be devoid of legitimate protest about our country’s moral and social failures.

What if people excoriated as unpatriotic, as traitors, as people who don’t love America turn out to be real patriots — people who demand justice, righteousness and liberty for all? These are the people who make like Amos to cry, “I hate, I despise your patriotic festivals, and I take no delight in your gaudy displays of red, white and blue in your sanctuaries. Even though you wave all those flags, I will not honor them. Take away from me the noise of ‘America.’ I will not listen to your epideictic perorations of empty patriotic praise. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

Too many Americans today operate out of a childish version of patriotism that values public displays over real-life democracy.

“Too many Americans today operate out of a childish version of patriotism that values public displays over real-life democracy.”

My grown-up self prefers the robust democratic spirit of Walt Whitman: “O Democracy, for you, for you I am trilling these songs.” Give me a call for a society based on equal access to opportunity and equality before the law.

William Sloane Coffin hit all the right notes: “There are three kinds of patriots, two bad, one good. The bad ones are the uncritical lovers and the loveless critics. Good patriots carry on a lover’s quarrel with their country, a reflection of God’s lover’s quarrel with all the world.”

Good patriotism

Good patriotism strives to build a common, shared American identity. Patriotism preserves and develops shared national identity. It binds together the bonds of a common civic life. It refuses to waste good air making enemies of fellow Americans and driving a wedge between us with cries of a “coming civil war.”

There’s a loyal opposition in true patriotism, not a collection of enemies.

Dissent, protest, conflict, argument — these are the terms of patriotism. When we are the best patriots, we are fiercely engaged in debates about the values Americans will inhabit. Barbara Tuchman wrote, “A nation in consensus is a nation ready for the grave.”

“Patriotism dwells with those ‘who more than self their country loved.’”

Where in America does patriotism live? Patriotism dwells with those “who more than self their country loved.” Patriotism lives with those who go about doing good, repairing a broken world, who oppose America’s entrenched fondness for exploiting nature for profit. These are the men and women unafraid to cry out, “God mend our every flaw.”

Patriotism lives in those who are willing to risk everything for the rights of the whole human race and its environment.

The true patriot is an “assaulter of the mind.” The true patriot doesn’t allow a nation to oppress people but perverts the paradigms of superiority and arrogance. As Gordon Wood, historian of the American Revolution, argues, a healthy disrespect for oppressive authority lies at the heart of the American spirit. The true patriot speaks the truth in love at great risk to herself.

Meet a handful of the carriers of the tradition of true patriotism.

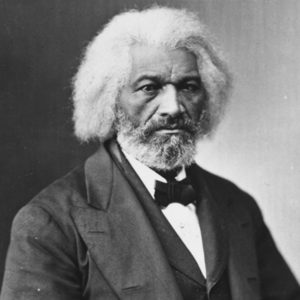

Frederick Douglass

President Barack Obama, speaking of Douglass, said that the “embrace of truth as best we can know it is where real patriotism lies.” Historian David Blight, in his magisterial biography of Douglass argued, “There may be no better example of an American radical patriot than the slave who became a lyrical prophet of freedom, natural rights and human equality.”

Frederick Douglass

Douglass had profound ambivalence about the concepts of home and country. “I have no love for America, as such,” he announced in a speech. “I have no patriotism. I have no country.” All that attached him to his native land were his family and his deeply felt ties to the “three millions of my fellow-creatures, groaning beneath the iron rod … with … stripes upon their backs.” Such a country, Douglass said, he could not love. “I desire to see its overthrow as speedily as possible, and its Constitution shivered in a thousand fragments.”

Frederick Douglas patriot? Does that unnerve you? Good.

Years later, Douglass envisioned a different America: “A government founded upon justice and recognizing the equal rights of all men; claiming no higher authority for its existence, or sanction for its laws, than nature, reason and the regularly ascertained will of the people; steadily refusing to put its sword and purse in the service of any religious creed or family.”

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman made at least 13 hazardous missions into the South to help free more than 70 slaves. When the Civil War began, Tubman worked for the Union Army, first as a cook and nurse, then as an armed scout and spy. The first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, she guided the raid at Combahee Ferry, which liberated more than 700 slaves. She was active in the women’s suffrage movement. She became an icon of patriotism.

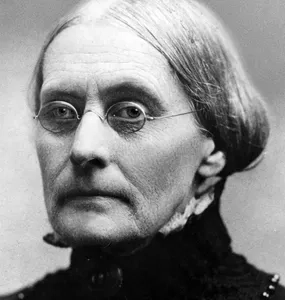

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony led the charge for women having the right to vote. In 1872, Anthony was arrested in her hometown of Rochester, N.Y., for voting in violation of laws that allowed only men to vote. She was convicted in a widely publicized trial. Although she refused to pay the fine, the authorities declined to take further action. The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920 is the legacy of her patriotism.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Charles M. Payne, in I’ve Got the Light of Freedom, documents long overdue recognition of Hamer’s patriotism. An early voting rights activist, Hamer said as soon as she heard people explaining what voting meant, “I could just see myself votin’ people outa office that I know was wrong.”

Fannie Lou Hamer

Arrested and jailed in Winona, Miss., several African Americans were beaten by jail deputies. Payne says, “When Mrs. Hamer’s turn came, the guards, perhaps tired by this time, had her lie face down on a bunk and ordered two Black prisoners to beat her with a studded leather strap until she couldn’t get up.”

On Aug. 22, 1964, she spoke before the Credentials Committee of the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. In this speech she uttered the famous quote: “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Hamer truly was one of the lights of freedom.

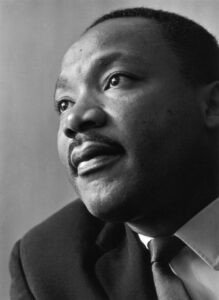

Martin Luther King Jr.

No one spoke more truth to more Americans than Martin Luther King Jr. The more patriotic King became in his preaching, the more despised he was among the people — at times, even his own people. His sermon against the war in Vietnam was a patriotic tour de force, but the nation refused to hear his words.

Martin Luther King Jr. (Photo by Reg Lancaster/Express/Getty Images)

One hundred and sixty-eight newspapers denounced him in the days that followed. The Washington Post claimed King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, and his people.” The New York Times, in “Dr. King’s Error,” reminded King that his proper battlegrounds were “in Chicago and Harlem and Watts.”

William Sloane Coffin Jr.

An Army officer in World War II, a member of the CIA, chaplain at Yale University and senior minister of Riverside Church, William Sloane Coffin was a true patriot. His involvement in the Civil Rights movement, the anti-war movement and the nuclear disarmament movement promote the value of patriotism.

Wliliam Sloane Coffin

He was convicted of conspiracy to aid draft resistance in 1967. He appealed his case and finally, in 1970, the whole matter was simply dropped. Coffin never was pardoned. As senior minister at Riverside Church, Coffin became the voice of liberal Christianity.

In a Fourth of July sermon, Coffin spoke eloquently of Lincoln calling Americans “God’s almost chosen people” and “the last great hope of democracy.” He bemoaned that America’s ship of state had lost headway and “maybe even direction.” He held out hope that most Americans did really love their country.

What story will you tell?

When you tell the stories of patriotism to your grandchildren, do not tell them of our generals, our tycoons, our wealthy. Tell them of the true patriotism that speaks hard truth to power. Tell them of patriotism that leads to soup kitchens, clothes closets, homeless shelters, free health care clinics. Tell them about patriotism that leads to more rights for women, minorities, the LGBTQ communities and immigrants. Tell them the stories of a nation bending every effort to care for God’s privileged classes — the poor, the widows, the orphans, the immigrants, the single mothers. Tell them the stories of the true patriots of freedom and dignity for all.

I can think of no nobler way to end than the words of President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address: “And so, my fellow Americans: Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world: Ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.”

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor in New York state and serves as a preaching instructor at Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

We don’t talk about Brittney | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Confessions of an unpatriotic Christian | Opinion by Chris Conley

Southern Baptist author urges distinction between love of God and love of country