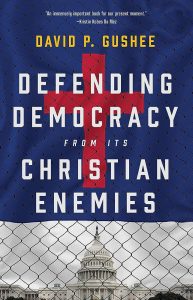

Like just about everybody these days, David Gushee is worried about the survival of democracy. His latest book, Defending Democracy from its Christian Enemies, addresses the problem of democratic “backsliding” or “deconsolidation.” As his title suggests, he calls out Christians as the primary culprits.

Gushee devotes the early pages of his book to a precise definition of “democracy.” He makes frequent references to the standards Freedom House uses to assign a democracy grade to nation states (the United States gets a score of 84/100, Hungry 45/100, and Russia a woeful 5/100).

“Democracy,” he says, “consists of popular sovereignty through the rule of laws that are not arbitrary but grounded in moral principles that the people themselves respect.”

“Democracy,” he says, “consists of popular sovereignty through the rule of laws that are not arbitrary but grounded in moral principles that the people themselves respect.”

Democracy is described as a species of faith into which citizens must be catechized. Churches could, and should, train people for democratic participation, but almost always fail badly.

Gushee describes himself as “a committed Christian, called to pastoral and scholarly ministry.” But he identifies “authoritarian reactionary Christianity” as the primary cause of global democratic backsliding.

That’s because we are witnessing yet another wave of a secular revolution that has been a feature of Western civilization since the dawn of the enlightenment in the 17th century. From the advent of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2015, we have witnessed a new anti-democratic militancy on the right featuring an adamant rejection of gay rights and of the need for racial justice.

“We have witnessed a new anti-democratic militancy on the right featuring an adamant rejection of gay rights and of the need for racial justice.”

The ferment isn’t just noticeable on the fringes of conservatism. Gushee observes that many Christians who, until recently, had been willing to tolerate a measure of “liberal, pluralistic, secular, democratic modernity” are now showing signs of “religiously and morally motivated authoritarian reaction.” His greatest fear is that “alienation and antagonism toward American culture” could lead to “a general opposition to the constitutional order.”

Gushee identifies “political authoritarianism” as “the antithesis of democracy.”

A strong streak for centuries

The author freely admits there has been a strong authoritarian streak in Christianity for centuries. Church and state both were characterized by “hierarchical and centralized power,” and there has been “no venue for individual or communal participation in the truth-discernment, interpretation and proclamation process.” In most religious systems, Christian and non-Christian, Gushee asserts, “the role of the people is to receive and obey authoritative teaching, not to debate what to believe.” If you don’t like what is being taught, there has been no “avenue for protest or appeal.”

The architects of the French Revolution (1789-1799) realized the Catholic Church was so deeply entangled with the ancien regime that religious repression had to accompany political revolution. The word “reactionary” was coined in 1797 to describe the forces, political and religious, that pushed back against this anti-monarchical and anti-clerical revolution.

In Gushee’s view, authoritarian reactionary Christianity was initially a response to enlightenment liberalism. It has been “a strongly negative reaction to modernity, democracy and pluralism, or to certain cultural, moral, political or legal developments in democratic societies.”

An existential threat

As authoritarian Christians react to what they perceive to be a coercive, top-down liberal agenda, secularists recoil in alarm. Both sides view the opposition as an existential threat. No one listens to the other side. In such an atmosphere, leading voices on both the right and the left begin to wonder if democracy can survive.

Catholic political scientist Patrick Deneen envisions what Gushee describes as “a post-liberal fight to the finish between two forms of illiberalism — left-liberal orthodoxy, on the one hand, and authoritarian reactionary religio-politics on the other, fighting over the carcass of liberal democracy.”

American democracy

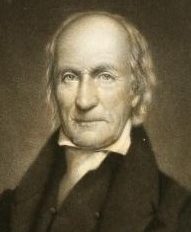

John Leland

American democracy, Gushee argues, is rooted in two very different sources: the political musings of John Locke (1632-1704), and the covenantal and congregational polity emerging out of New England Puritanism and its spiritual offspring. Baptist dissenters inherited much of their ecclesiology from the Puritans but, largely because they struggled for survival as a persecuted minority, they rejected authoritarianism and placed their hope in pluralistic democracy. And they did so, Gushee notes, long before Locke envisioned a democratic polity anchored by the protection of individual rights.

“Baptists initially fought for basic religious liberty of dissenting Christians like themselves,” Gushee says, but they soon saw that “the same principle also must apply to other religious minorities, including Jews and Muslims.”

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, with its rejection of an established religion, owes its existence to John Leland and other Virginia Baptists who lobbied for religious liberty. In the writings of Baptists like Richard Overton (1599-1664) “arbitrary government power was constrained on behalf of human rights protections,” which included “the right to free education for all and social insurance for the most vulnerable.”

“The enlightenment liberal idea of democracy has two major flaws.”

Although the Baptist contribution to American democracy has received little attention from historians, Gushee (following his mentor, Glen Stassen) argues for the superiority of the Baptist model. The enlightenment liberal idea of democracy has two major flaws: “its social imagination focused on individuals and their personal preferences” rather than prioritizing “communities and their shared needs,” and it contains no “shared account of the good life and the good community.” The enlightenment democratic model is “morally thin” because it lacks the resources needed for training “good citizens who can exercise responsible freedom.”

For centuries, Gushee believes, America’s crazy quilt of faith communities obscured the thinness of the enlightenment vision by generating a rough-and-ready moral consensus. As a consequence, America was able to avoid a fight-to-the-finish culture war between authoritarian conservatives and secular liberals.

That changed in the early 1960s, Gushee believes, as a second wave of secular revolution affirming civil rights, women’s rights and, eventually, gay rights washed over America. Gushee also identifies a third wave of secular revolution, although he cautions this may simply be a radicalizing of 1960s-style political and religious backlash.

Crowds gather for the “Stop the Steal” rally on January 6, 2021, in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images)

January 6

He emphasizes, however, that “January 6 was the culmination of authoritarian tendencies visible from the moment the Trump campaign launched. It marked a terrible advance in the radicalization of a significant number of authoritarian reactionary American Christians.” Conservative Christians lined up behind Trump because he presented himself as the champion, indeed the embodiment, of the authoritarian reactionary counterrevolution they were calling for. This explains his abiding popularity.

But Gushee sees Donald Trump as a symptom of a global cancer. He argues the term “Christian nationalism” is too tied to recent American realities to appreciate the global and historical significance of recent trends. He prefers the term “authoritarian reactionary Christianity” because it ties the events on the evening news to earlier epochs (such as the French Revolution, or 19th century precursors to the Third Reich), while also connecting the dots between Trumpist religion and Vladimir Putin’s manipulative embrace of Russian orthodoxy, Viktor Orbán’s “illiberal democracy” in Hungary, or Jair Bolsonaro’s unholy alliance with evangelicals and charismatic Catholics in Brazil.

Gushee takes his readers on a whirlwind tour of three seminal figures in 19th century Germany who cobbled together a “Germanic-pagan” faith that drained Christianity of its Jewish roots and paved the way for the Deutsche Christen movement of the 1920s.

“When one tunes in to some of the worship services of the most ardent Trumpist pastors in America,” Gushee observes, “quite often the anger, hyper-masculinism and militant nationalism presented there bear no resemblance to Jesus or historic Christianity. Something debased and alien is going on.”

“It is a strategy of evoking disgust for a group of vulnerable people and then leveraging that disgust to gain political power.”

A single theme emerges from Gushee’s nation studies: the vilification of the LGBTQ community. “It is a strategy of evoking disgust for a group of vulnerable people,” he laments, “and then leveraging that disgust to gain political power.”

Gushee asserts neither the enlightenment/liberal vision of democracy nor the authoritarian reactionary Christian alternative provides a viable vision for the common good. Our situation is particularly dire because neither side is showing the slightest interest in understanding the other.

‘Mediating voices’

There is, therefore, a desperate need for what Gushee calls “mediating voices.” That is precisely what he is trying to bring to the table.

Especially since he emerged as a champion of gay inclusion, he often has been written off as “a man of the left.” Although he admits to being reliably “center-left” on most issues, he insists he has “arrived at that ideology not via MSNBC but through my reading of the biblical prophetic tradition and the teachings of Jesus” (author’s emphasis).

Three resources

In his concluding chapters, Gushee offers three resources for defending democracy: The Baptist democratic tradition, the Black Christian democratic tradition, and “renewing the democratic covenant.”

“In the public mind, Baptists are rarely viewed as defenders of democracy.”

Gushee realizes that, in the public mind, Baptists are rarely viewed as defenders of democracy. That is largely because the word “Baptist” usually brings to mind the decidedly authoritarian reactionary Southern Baptist Convention. Still, as Glen Stassen saw, Baptist congregations once served as “laboratories for democracy” and can do so once more.

Gushee ends his chapter on the Baptist democratic tradition on a wistful note. “In our world,” he says, Christian support for antidemocratic politics “has its own long pedigree — and is on the march today.” Then he shares “a very disturbing idea”: “It may be that the Baptist democratic Christian vision is more of the aberration.”

James Cone

Gushee reserves what he calls “the Black Christian democratic tradition” for his penultimate chapter. As a doctoral student at Union Theological Seminary in the 1980s, he listened to James Cone say that until “whiteness” is “uprooted, defeated and repented, there can be no genuine democracy in the United States.”

When “the father of Black theology” spoke of “whiteness” he wasn’t talking about a skin color. “Whiteness” is “a name for this evil power that damages everything it touches, not just its non-white targets but also the souls of white people and the moral integrity of white-damaged Christianity.”

At the time, Cone’s rhetoric struck Gushee as “radical.” But after witnessing “everything that happened in the United States from 2015 forward,” Gushee has come to agree with his mentor. Whiteness is a lens through which people see the world, but “this lens is invisible to the ones using it.” Which explains why “white people generally react with incomprehension or paroxysms of rage if its existence is proposed.”

The critique of whiteness has become as sharp as razor wire in recent years and, through the wonders of social media, has impacted a much wider audience. Two mutually exclusive American origin stories are vying for preeminence.

Randal Jelks describes Black history as “contrapuntal” to the story white Americans are used to hearing because it defies “the idea that people in the United States are God-fearing.”

As one would expect, the backlash in white America has been ferocious. Gushee worries “the violent religious-nationalist potentialities” that were everywhere on display in the 1960s “have recently been revived after lying dormant for generations.”

If the unmasking of white racism has created so much incomprehension among authoritarian reactionary Christians, how can it also serve as a resource for defending American democracy? “Democracy must be fought for,” Gushee reminds us, which is why “those who have had to claw their way into political enfranchisement” understand the demands of democracy so well.

In his final chapter, Gushee explains how mediating voices can “renew the democratic covenant.” Churches need to take their marching orders not from secular liberalism, but from “the prophetic tradition of social justice and the prophetic promise of a transformed creation; and the life, teaching and example of Jesus.”

Churches must use this faith story to encourage “robust church participation and training in virtue, … compassion, responsibility, service, honesty and wisdom.”

In the process, Gushee says, “we can reject authoritarianism, embrace democracy” and live harmoniously “in societies with profound diversity of belief.”

“Gushee hopes churches, particularly those in the democratic Baptist tradition, can serve as mediating voices within a warring culture.”

Gushee hopes churches, particularly those in the democratic Baptist tradition, can serve as mediating voices within a warring culture. But this can’t be done by living in the mushy middle.

David Gushee has emerged as a stalwart defender of gay rights and racial justice. He believes the American story needs to be retold from the perspective of the oppressed. American Christians can’t follow his guidance if we ignore these core ethical challenges.

How many Baptist churches are prepared to join Gushee outside the camp of standard-issue American Christianity? I belong to such a church. Maybe you do too. It seems certain, however, that churches inspired by the Baptist democratic tradition will be just as small and socially marginalized as their colonial antecedents. Only so can we hope to be the kind of immoderate mediators Gushee is calling for.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas.

Related articles:

Devouring beasts: Advent and the 2024 election | Opinion by David Gushee

My argument in Defending Democracy from its Christian Enemies | Opinion by David Gushee

Christ is now a threat to radicalized Christians, Gushee warns in new book