There’s a thin line between reading a memoir written by somebody who grew up in conservative Christianity and watching a horror movie.

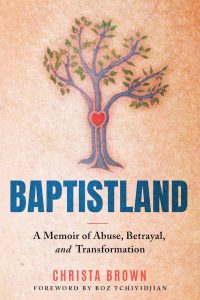

As Christa Brown, a frequent contributor to Baptist News Global, releases her new memoir Baptistland: A Memoir of Abuse, Betrayal, and Transformation, it’s hard to miss the parallels between the horror she and many of us have faced in conservative Baptist churches and the trauma Sydney Sweeney’s character named Sister Cecilia experiences in the new horror film Immaculate.

One is fictional and one is nonfiction, but the stories harmonize.

And just as Brown has been demonized by being labeled a “spawn of Satan,” so has Sweeney’s film.

Catholic Review called Immaculate “a vile piece of horror tripe,” “morally offensive,” said it “contains blasphemy” and claimed “the viewpoint is entirely secular rather than Protestant while the animus is more broadly anti-Christian.”

According to Focus on the Family, the central message of Immaculate is that “religion needs to become extinct.”

Reaction to the movie from many on the right has been so strong that Neon, the production company behind the film, began using some of the criticisms in their marketing.

According to one user on X whom Neon quoted for a T-shirt, Immaculate is a “blasphemous, satanic, feminist, pro-abortion, anti-life movie degrading Christians! This movie also debases Mary, mother of Christ!”

According to one user on X whom Neon quoted for a T-shirt, Immaculate is a “blasphemous, satanic, feminist, pro-abortion, anti-life movie degrading Christians! This movie also debases Mary, mother of Christ!”

“Diabolical, sacrilegious, pure evil and grossly offensive,” wrote another. “It is profane and has a third act that spits in the face of all that is holy. Just … evil.”

But as the stories of Sister Cecilia and Christa Brown remind us of the sexual abuse scandals within Catholic and Baptist churches, one begins to question who is really spitting in the face of all that is holy.

When the church is the monster

While most horror movies depict the church as the hero providing exorcisms, director Michael Mohan’s Immaculate opens up a conversation about the most horrific experiences many people today have faced from the church.

It tells the story of a young American woman named Cecilia who is spared from drowning as a child and grows up to join the nuns at a convent in Italy called Our Lady of Sorrows that was built over the catacombs of Saint Stephen, the first Christian martyr.

After taking the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, Sister Cecilia looks forward to adjusting to her new home and serving God inside the walls of the church for the rest of her life. But she soon discovers she’s in a nightmare she fears she’ll never escape.

When she learns she’s pregnant, despite never having had sex, the leaders at the convent tell her she has to be like Mary and give birth to the child in order to save them.

Similarly, in Baptistland, Brown recalls church leaders telling her to be like Mary as well. “If Mary hadn’t been willing to trust in what God wanted of her, however crazy it seemed, then human beings for all time eternal would be in hell without a Savior,” Brown writes. “And we aren’t talking some mere metaphorical hell. The church I grew up in dished out a constant threat of a hyper-violent hell where those who rejected God would burn forever in a fiery inferno without ever getting the relief of burning up.”

In other words, while both stories appeal to Mary’s innocence, their theologies of justice cause children to lose their innocence.

The commitment of the innocent

The way Cecilia’s innocent commitment to God is taken advantage of by church leaders is similar to the experience Brown shares.

“The way Cecilia’s innocent commitment to God is taken advantage of by church leaders is similar to the experience Brown shares.”

In an interview with Baptist News Global Executive Director Mark Wingfield, Brown recalled: “I was, from toddlerhood on, indoctrinated in the belief that these were men of God and that it was my role to be submissive and my role to accept what they said, not just because they were men but because they were carrying the authority of God. And I was a girl who loved God heart and soul and sought only to please God. And with that kind of indoctrination, I can’t imagine how I could have done anything other than what I did. That was the fish bowl that I lived in. That was my whole environment. It was Scriptural. ‘Lean not unto thine own understanding.’ ‘Obey them that have the rule over you for they watch over your souls,’ which was kind of important if you thought that your soul might otherwise burn forever in hell. It’s as though faith itself was a part of the grooming process for sexual abuse and certainly facilitated the coverup of it and helped to keep me silent.”

‘Suffering is love’

In Immaculate, when Cecilia discovers the convent claims to own one of the nails that crucified Jesus, one of the nuns talks about the suffering of Christ for sin and salvation, and then adds: “We suffer in the name of his love. It is a gift. Suffering is love.”

In her book Sex, Tech and Faith, Kate Ott discusses how penal substitutionary atonement theology gets used to justify abuse by celebrating violence: “While violence is part of the Christian story in a variety of ways, when we celebrate this violence and certain theologies that surround it, we silence those who experience various forms of violence.”

Simona Tabasco in Immaculate (IMDB)

The way the “glories of the Cross” are celebrated in conservative worship services, those who have been beaten, bruised, pierced or who have seen their fathers’ faces turn away are in an environment where these very same actions are stirring excitement. Thus, penal substitutionary atonement theology turns the worshiper into a bystander, benefactor and blesser of violence against a human body.

While motivating worshipers with the suffering of Christ, pastors and worship leaders invite the worshiper into suffering as well. In high-control religion, this means submitting to the authorities, no matter how ridiculous or coercive their rules may be.

As Brown illustrates in Baptistland, men met among themselves to debate whether the teenage girls should be allowed to wear slacks at church camp or whether the church should purchase cushions for their wooden pews. The men decided against providing cushions. Brown remembers, “Since Christ had suffered so horribly for us, surely as Christians we could bear sitting on wooden pews for him.” One of the deacons added, “Maybe it would even help to remind us of Christ’s suffering.”

‘I’m afraid I’ve already messed things up’

In one scene at the confessional booth, Cecilia says, “I promise to carry myself with grace because I want nothing more than to belong here. I’m afraid I’ve already messed things up.”

Her innocent desire to serve God, paired with her sense of being the one to blame is similar to Brown’s experience in Baptistland. Brown told Wingfield: “I think people would like to believe this happens somehow to kids who lack morals or something. But nothing could be further from the truth. Because the truth is, what made me the most vulnerable to this type of predator was my own faith. Faith is what made me vulnerable because that is what was twisted and used against me. It was the very fact that I loved God so much that made me vulnerable to his abuse. And that’s what makes this crime so terrible I think, because the kid is left with the sense that God has willed this and wanted this.”

This is what happens when kids are taught the Bible in children’s church through a law and punishment paradigm. Beginning in Genesis 1-3, every story is framed in a law and punishment narrative that warns kids of the violent eternal punishment of hell they supposedly deserve.

“Out of gratitude, they can follow Jesus in suffering by submitting to their authorities just as Jesus submitted to his.”

But then the story twists to say Jesus was violently punished in their place. So out of gratitude, they can follow Jesus in suffering by submitting to their authorities just as Jesus submitted to his. Thus, any violence the child experiences feels to the child like it’s better than the violence they really deserve and is part of following Jesus. The child continues to submit their minds and bodies to the trauma because they want nothing more than to belong.

Women have no bodily autonomy

The rest of this article is going to contain major spoilers and trigger warnings regarding sexual violence.

As Immaculate unfolds, questions are suppressed and anyone who asks them is dealt with violently. The women are not to be seen or heard outside the walls and roles those at the top of the hierarchy have built for them.

The women losing the autonomy of their tongues also lose the autonomy of their sexuality.

A scientist who works at the convent claims to have extracted Jesus’ blood samples from the nail and somehow used the DNA to impregnate Cecilia without her knowing. The scientist tells her God gave her to them as “the perfect, fertile vessel.” Thus, as the vessel of a God who works through church leaders, Cecilia is obligated to endure whatever suffering the church leaders put her through. Not only does this require the complete denial of her sexuality, but it includes being impregnated and giving birth against her will.

It’s a hard story to watch. And many will deny how realistic the movie is, given that it’s set in the horror genre. But as Brown notes, that’s what happens in the real world as well beyond simply the shock of the horror genre.

It’s a hard story to watch. And many will deny how realistic the movie is, given that it’s set in the horror genre. But as Brown notes, that’s what happens in the real world as well beyond simply the shock of the horror genre.

Regarding her book, “I realize these stories are really, really dark and awful stories,” she told BNG. “And I think that is why many people seek to deny the reality of them. Because we don’t like to believe that such dark and awful things happen.”

In Baptistland, Brown elaborates: “The very essence of evangelical faith is the relinquishment of personal autonomy with an all-encompassing surrender to a higher authority.”

Angels of light

During perhaps the turning point of the film, a picture falls, revealing to Cecilia the words from 2 Corinthians 11:14. Including the verses before and after it, the message is: “For such boasters are false apostles, deceitful workers, disguising themselves as apostles of Christ. And no wonder! Even Satan disguises himself as an angel of light. So it is not strange if his ministers also disguise themselves as ministers of righteousness. Their end will match their deeds.”

In other words, the implication of the film is that this convent is being run by ministers of Satan disguised as ministers of Christ. So rather than demonizing Christianity, it’s actually saying the exact opposite, possibly coming close to a “No True Scotsman” fallacy.

But Focus on the Family and the conservative Christian critics are so up in arms over the film that they think it’s an attack on the church, just like they think Christa Brown standing up to abusers is an attack on the church.

And maybe they’re right, given how so many branches of the church have defined reality as a sovereignty hierarchy of authority and submission.

As Brown explains in Baptistland regarding the hymn “All to Jesus I Surrender”: “Despite the words of the song, it’s not really a ‘surrender’ that you ‘freely give’; instead, it’s a ‘surrender’ given to avoid eternal hellfire. Sometimes I think this single hymn may say everything anyone needs to know about the faulty foundation for evangelical notions of consent: give everything or get damned for all eternity. Talk about a power differential. And once you ‘surrender all,’ that singular decision gives tacit consent, not only to God, but to the whole God-ordained chain of command: God, pastor, husband, wife, child. Kids are at the bottom, so kids are expected to surrender to pretty much everyone. Faith demands it. And I was a girl of infinite faith. Heck, if Abraham had told me to lie down on the sacrificial altar because God said he should plunge a knife into me, I might have hopped up onto that altar and shouted ‘Hallelujah!’ That’s how surrendered I was.”

It’s that hierarchical chain of command that is the problem — humans posturing themselves over one another in the power dynamics of empire while disguising themselves as ministers of righteousness.

Liberating yourself

There comes a time in every survivor’s life when you realize you have to get out in order to save yourself. For Cecilia, this walk out of the convent means using the cross and the rosary to bring the ministers of Satan to an end that matched their deeds. It also means wielding the nail that was used to impregnate her as a weapon to fight off the one who used it during an attack.

Like the story of Jesus, the empire Cecilia faced is destroyed by the tools it wielded over the people it oppressed.

What has conservatives most riled up is the ending, during which Cecilia gives birth to whatever the church had planted inside her, hears a growling sound coming from it, and smashes it with a rock.

Because the leaders at Our Lady of Sorrows claimed it was a baby and was the next Jesus, conservatives are saying the final act was a pro-abortion message that hints at aborting Jesus.

“What conservative Baptists have that makes the problem even worse is an individualized theology of sin that refuses to examine systemic evil for fear of being called ‘woke.’”

But given how Cecilia was impregnated with a creature who was making an inhuman sound, it’s far more likely that the scene is meant to depict the imagery of a woman not being beholden to the fruit of abuse.

For Mohan, the director of Immaculate, it was part of the healing process of giving expression to the anger we feel about what the church has put into our bodies against our wills.

“Everyone right now struggles with faith, right? There’s a lot of people (who) are angry out there, and I want this film to bottle up that sense of anger and give them that sense of catharsis leaving the theater,” he said.

In a similar way, Baptistland tells the story of how Brown walked out of the church, fought against its leaders and refused to accept the fruit of their abuse. For her, the creature growing within during the stress of confronting the coverups of the patriarchy was cancer. And like what seems to be implied in Cecilia’s story, the offspring of patriarchy is not flourishing humanity but a monstrous tumor.

Catholics and Baptists together

Of course, many people will hear about Immaculate and think, “That’s a Catholic story. Baptists aren’t like that.” But as Brown notes, that’s exactly how conservative Baptists responded to the sexual abuse horrors that were being exposed in Catholicism in the 2000s.

Ultimately, despite their many differences, Catholics and conservative Baptists share common theologies of hierarchical authority that prevent institutional accountability. But what conservative Baptists have that makes the problem even worse is an individualized theology of sin that refuses to examine systemic evil for fear of being called “woke.”

The result is indeed a reality of horror that horror movies can only begin to give us a glimpse into. But like Cecilia and Brown, the way out can lead to healing and liberation when we are willing to face the darkness, remove the perpetrators, deal with the abuse on both an individual and systemic level, deconstruct the theology that sacralizes it, and connect in empathy for self and neighbor.

As Brown explains: “Speaking out about Baptist clergy sex abuse began to feel like an endless Whac-a-Mole exercise in some sadistic, surreal circus. Hundreds of names began to blur in my mind. As soon as one predatory pastor was knocked down, another would pop up. The problem was systemic, but it seemed people in Baptistland simply didn’t believe in systemic issues. With a theology oriented toward individual sin and individual piety, their lens was limited, which in turn constrained any notions of institutional accountability. So the cycle continued, again and again, with survivors mustering media attention, only to have SBC leaders say or do some tiny something to momentarily give the illusion of caring before they showed the institution’s true recalcitrant colors. … Transformation always begins with truth-telling, first to ourselves and then to others. Truth-telling holds value across time and it is the foundation for all reform — both individually and institutionally.”

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related article:

Church life is the perfect cover for abusers, Brown says in BNG webinar