Last fall, I had the great honor of serving as a visiting fellow at the Oxford Center for Religion and Culture, headed by the renowned Black liberation theologian Anthony G. Reddie. Anthony and I became fast friends, and we had important conversations about how the world, the university and the church need to change.

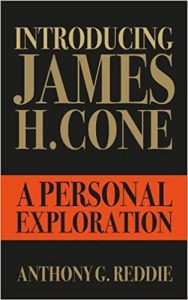

When I learned he was writing a book about James H. Cone, I was excited and wanted to share that book with my BNG readers, since I agree with Professor Reddie that James Cone is an essential writer for all Christians. Here’s the conversation I had with Reddie about his new book Introducing James. H. Cone: A Personal Exploration.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett: You say James H. Cone is perhaps the greatest theological voice of the 20th century, are leading a revolutionary seminar on him at the University of Oxford this fall, and write that Cone’s has “a radical and revolutionary understanding of Christian theology that is grounded in and based on the lived experiences of and the existential realities facing Black people in the world.” Can you summarize for my readers — who I hope will also be your readers — why Cone matters so much and also why you feel such a strong sense of personal connection to his writing?

Anthony Reddie

Anthony Reddie: Cone matters for three principal reasons.

He is the creator of a major intellectual movement — the first theological articulation of Blackness and that what has been despised and ridiculed for centuries is now seen as the medium through which God’s revelation is made manifest. Cone’s theology of Blackness refutes the centuries of anti-Black racism that has dominated American life.

Cone’s theology has been one of the fundamental resources for exposing the death-dealing ways of white supremacy and how this is America’s “original sin.” No one has done more to “call out” the hypocrisy of white supremacy and its claims to be Christian, worshipping a white Jesus who colluded with slavery, Jim and Jane Crow, lynching and segregation, and more recently the horrors of the presidency of Donald Trump.

Cone has been one of the fiercest defenders of the development of Contextual Theology. In creating his Black theology of liberation, Cone focuses on American history and the lived experiences of African Americans as providing the raw materials for a theology that challenges oppression and marginalisation in North America.

“His focus on America is one that has proved to have universal implications.”

Whilst Cone is not talking for every context of oppression, his focus on America is one that has proved to have universal implications. But Cone’s way of providing universal truths is through the prism of a focus on particularity, the specificity of the Black experience as a means of speaking of the universal tenet of a God of the oppressed whose primary qualities are those focused on liberation.

GG: There’s a tendency among some white Christians to think of Black theology (or womanist theology, or queer theology) as a secondary subset of theological study. “Theology” is white theology, whether that sentence ever gets said out loud. What does James Cone have to say to white Christians that they absolutely need to hear? How might his work (and yours, and Kelly Brown Douglas’ and those other heirs to Cone’s teaching) reshape the church and the culture for the better?

AR: The central aspect of the work of the aforementioned has been one that has seen the work of Black (and womanist) theology as critiquing the alleged superiority of white people or the notion that “whiteness” should predominate. In using the term “whiteness” I am referring to the lens through which we see the world and how social and economic relations are organized for the benefit of white people. The relationship between the empire, colonialism and Christianity, in many respects, remains the unacknowledged elephant in the room.

“The relationship between the empire, colonialism and Christianity, in many respects, remains the unacknowledged elephant in the room.”

Empire and colonialism became the basis on which notions of white supremacy were based. The intellectual underpinning of white supremacy, the notion that white people are superior to peoples who are not white, was based on a corruption of Christianity in which whiteness was conflated with the Christian faith.

Our work has sought to free white people from the sins of white privilege and entitlement. This may not be seen by white people as a gift, but it is. Paulo Freire in his wonderful book Pedagogy of the Oppressed argued that only the oppressed can free themselves and those who oppressed them. The powerful cannot free themselves, as they have too much to lose and are too embroiled in the status quo to change without having been made to do so.

GG: We talked last fall during my time with you at the Oxford Center for Religion and Culture about the strangeness of practicing liberation theology from the heart of the empire. (I have that feeling in a slightly different fashion when I go speak in the American South!) Are you encouraged that Oxford has accepted your lectures on Cone as a part of the theology curriculum? What do you still perceive as challenges for a Black theologian at Oxbridge?

AR: I am very much encouraged by my place within Oxford University. Of course, one cannot overestimate the significance of the murder of George Floyd. His murder has changed the landscape of the university. I am not sure the landmark course on James Cone would have been agreed were it not for the change that has emerged following George Floyd’s tragic murder.

AR: I am very much encouraged by my place within Oxford University. Of course, one cannot overestimate the significance of the murder of George Floyd. His murder has changed the landscape of the university. I am not sure the landmark course on James Cone would have been agreed were it not for the change that has emerged following George Floyd’s tragic murder.

One of the continued challenges is to try and enable the continued development of Black theology in such a way that more people have exposure to it and can be influenced by its ideas. At the time of writing, the course I am offering is a third-year option for 10 students only. My hope would be that there will one day be a range of courses in Black theology across all three years for undergraduates and possibly at master’s levels.

I want Black theology to become a part of the lifeblood of the theology and religion departments within Oxford University.

GG: One of my favorites of your teachings is around decolonizing the church and the curriculum, a divisive topic in the United States in this moment as conservatives sow fear about Critical Race Theory or “wokeness,” by which it seems they mean any constructive engagement with race in our history and national life. Do you find similar problems culturally in the UK? What does Cone bring to the project of decolonizing, and why should people of good conscience lean into it?

AR: In the wake of the Church of England’s 2021 Racism Task Force report From Lament to Action, a number of conservative Anglican commentators used social media — particularly Twitter — to argue that the report was the latest in an unfortunate trend of so-called “woke theology” being adversely impacted by the existence of Critical Race Theory. The culture wars in the UK are not as pernicious or as polarized as they are in the U.S., and that is largely because we do not have an extreme religious right as you have. Our opposition is less to do with a critique of CRT and has more to do with a support for empire, the glories of the British past, and the defence of colonialism.

“Black theology is not an example of woke ideology, rather, it has everything to do with the Judeo-Christian God who is revealed in the Bible.”

I have argued repeatedly in my writing that drawing on the work of Cone, the way in which one refutes the lies of the religious right is by reminding people that Black theology is not an example of woke ideology, rather, it has everything to do with the Judeo-Christian God who is revealed in the Bible.

Cone’s importance to the decolonizing church is through his focus on Jesus’ identity as a colonized and oppressed Jew. Namely, that the center of the Christian faith is on a colonized and oppressed man, through whom God seeks to transform the world. Cone’s work reminds us that the church post-Constantine is a usurper of the true, radical message and teaching of Jesus of Nazareth.

GG: What is your favorite book or article by Cone? Do you have an underappreciated work that your book suggests we should pay more attention to? Why?

AR: My favorite book by Cone is God of the Oppressed. My favorite article is his 2002 piece in the journal I edit (Black Theology: An International Journal) “Theology’s Great Sin: Silence in the face of White Supremacy.” I think his most underappreciated book is For My People, his first autobiography. It offers a more personal appraisal as to why he undertook his revolutionary work in Black theology.

GG: You and I both find ourselves walking into rooms full of white people (that is, people who look like me) to engage them in theological conversations about Christianity and racism. We’re doing a film series on race and religion this fall, since we both know that shared story can help engage people in hard conversations. What else might help people initiate antiracism efforts? What is your best advice (practical or otherwise) to folks wanting to lead this important work within the church?

AR: The use of film is a hugely important medium for theological reflection because stories matter. We know that stories generate meaning. One of the important factors in how we talk about race is to help to reflect critically on their stories. Postcolonial scholars often speak about the “root” and “route,” a kind of alliteration in the UK.

The “root” are the influences that have shaped us, for good and for ill. The “route” is the metaphorical, spiritual or physical journeys we all take across life’s journey. As a Christian theologian, I believe we can change. I believe if we are open to God’s redeeming and transformative spirit and are prepared to do the hard work of wrestling with the negativity of inherited racism and privilege from the wider cultures, from the “root,” then we can be transformed and changed for our continued journey across our “route.”

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. One of his most recent nonfiction books is In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett. His latest book, A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation, is hot off the presses. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

James Cone and becoming Black with God | Opinion by Amy Butler

In Georgia, demonizing Black Liberation Theology yet again | Analysis by Steven Harmon

This Good Friday, I’ll be at the hanging tree | Opinion by Stephen Shoemaker