Lynn Tramonte is both committed and consistent when it comes to advocacy for immigrants.

The author, writing coach and nonprofit leader is motivated by her own concern for the plight of the world’s refugees and immigrants. And regardless of who’s in the White House or Congress, she’s going to hold them to account.

Tramonte is founder and president of Anacaona, a communications firm, and she’s also founder and director of the Ohio Immigrant Alliance. She writes frequently for other publications, often on issues of immigration. In December 2021 alone, five of Tramonte’s articles appeared on the website of Interfaith Immigration Coalition, a partnership of faith-based organizations committed to championing a fair and humane immigration reform.

Lynn Tramonte

Her articles, whether they are about Cameroonians seeking Temporary Protected Status in the United States or about Haitians being deported in droves by the U.S. government, show her concern for the plight of the people who often cannot speak for themselves.

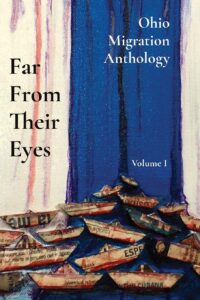

This is the same commitment and advocacy Tramonte brought to bear in Far from Their Eyes, a book she edited. Published in 2021, the book tells the stories of some Africans, two of whom narrated their experiences in the hands of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The idea for the book was borne out of the need to document what was happening during Donald Trump’s tenure as U.S. president, she said.

While the portrayal of ICE officials in the Trump administration is anything but positive, Tramonte said she looks forward to publishing volume two of the book, which she hopes will be more fun.

“The first volume of the anthology was put together during the Trump administration and so it’s very dark — there’s the holocaust, there’s Sudan, lost boys, there’s the racism in jail, really sad and scary things and I really hope that the next volume is a little bit more joy, … more positive with different topics,” she said.

She spoke about this and more in an exclusive interview with Baptist News Global.

Last year saw a huge number of Afghan citizens relocating to countries like the United States, after the fall of the Afghan government and the seizure of power by the Taliban. What’s your reaction to the situation that led to many Afghans fleeing their country?

It was devastating to see the U.S. government withdraw in such a chaotic way, not having a plan for the people of Afghanistan to be safe. I don’t care that President Trump is the one who started the withdrawal. Biden’s administration is the one that completed it, and they had no plan for the people that were going to be in a really dangerous and scary situation when the U.S. left.

Afghan refugees line up for food in a dining hall at Fort Bliss’ Doña Ana Village, in New Mexico, where they are being housed, Friday, Sept. 10, 2021. The Biden administration provided the first public look inside the U.S. military base where Afghans airlifted out of Afghanistan are screened, amid questions about how the government is caring for the refugees and vetting them. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Some people felt kind of some good about themselves because the United States said they would open (the country’s) doors to people from Afghanistan but the people they were talking about were the people who put their entire families in danger in order to assist the U.S. government (achieve) its objectives. So, we owe them the right to come here and be safe.

What about the other people? What about the children and families and elderly people, the young boys and girls, men and women, those just left there with (no help and) infrastructure. So, I think the U.S. Afghanistan withdrawal is a good example of how the U.S. (presents its) humanitarian foreign policy but in reality just leaves devastation and turns its back on people.

There are many Afghans now residing in America. Given your work in the area of migration, have you come in contact with some of them or heard their stories about their experiences in Afghanistan and the U.S.?

I have not met any Afghan people who have come in the last few months. I do work for different organizations that are helping refugees and the Afghan people and it’s a scramble right now to try to build up the humanitarian infrastructure inside the U.S. to help people get a house, get the utilities set up, get stabilized, get clothing, furniture. For example, in Ohio, the weather is very cold now.

So learning about what kind of clothing you need to wear to protect yourself from the cold. … I mean, it’s a completely new way of life so there’s a lot of work that the nongovernmental institutions are doing and there’s been an outpouring of donations and volunteers who want to help. That has been very beautiful, and it shows the beauty of the American people, that they want to help in that way. I wish that the government reflected that love for other people.

I just finished reading Far From Their Eyes, which is a collection of works. I find it insightful as it reflects different sides of migration seen through the characters. How did the idea of the book come about?

I was speaking with my cousin Kevin, and he does not work in immigration at all. But with the Trump administration and the way that they changed our immigration policies, more people who did not work on immigration were starting to learn about how evil and inhumane the policies are. (Kevin) has a background in writing and literature and he said, “Hey, these are important stories; we should do an anthology.” And I thought it’s a great idea because we are trying to reach the American people and let them know that immigrants are part of our communities.

I was speaking with my cousin Kevin, and he does not work in immigration at all. But with the Trump administration and the way that they changed our immigration policies, more people who did not work on immigration were starting to learn about how evil and inhumane the policies are. (Kevin) has a background in writing and literature and he said, “Hey, these are important stories; we should do an anthology.” And I thought it’s a great idea because we are trying to reach the American people and let them know that immigrants are part of our communities.

So we decided to create this anthology to say it’s a migration anthology, not an immigration anthology, because we wanted to talk about migration as a human condition, something that happens from one country to another but also from one state to another and it happens for many reasons but often it’s not out of choice. So we invited African Americans whose families migrated north from the Deep South to find work to submit (their) work and we invited a woman whose parents survived the Holocaust concentration camps and lost many loved ones there to submit her work. The opening of the book talks about the first people who lived on the land that’s called Ohio and how all our first peoples in Ohio have been pushed out.

It’s strange because “Ohio,” the word, is a Native American word and many of our counties and cities and parts all have Native American names. That’s the only thing that remains of the native peoples in Ohio. The rest were pushed out or killed.

So, I just wanted to make sure people who think they don’t have a connection to migration (know) that we all do. That unless our ancestors literally evolved on the land we are living on now, we all migrated from somewhere and so we should not judge or criminalize other people or demonize other people because they made a choice or they were forced to leave their country to go somewhere else. We should show them the compassion we would have wanted our ancestors to be shown.

The book, from the point of view of the African characters, sheds light on the attitude of some ICE officials. Was there any feedback from ICE after the publication?

I have not received any feedback from them. I don’t even know if they are aware of it. It seems like the only way to get their attention is to file a lawsuit. Some of the people who were interviewed in our book were very brave and spoke out about the racism and violence they were experiencing by corrections officers while they were in detention.

They documented that and communicated about it, and some lawyers were able to take that information and file a lawsuit that’s still going on, to try to say, this was not OK, you cannot punch people in the face, call them monkeys and keep them locked up in cages for 22 hours a day.

They documented that and communicated about it, and some lawyers were able to take that information and file a lawsuit that’s still going on, to try to say, this was not OK, you cannot punch people in the face, call them monkeys and keep them locked up in cages for 22 hours a day.

While the Department of Homeland Security may not like what we showed in the book, they have the power to change that behavior. And I am so just in awe of Saidu Sow and Mory Keita, who are in the book. … It was very dangerous for them to speak up because they could be punished and harmed and retaliated by the corrections officers. They were brave enough to speak up publicly and because of their bravery there’s a lawsuit now that I hope will make sure that the government changes its behaviors and doesn’t harm people in the future.

The book’s cover shows Volume 1. Do you plan to have Volume 2?

We do, and readers are invited to submit artwork for the Volume 2. The only characterization or qualification is they have to have a connection to Ohio. It can be about anything, but it has to have some migration history and some connection to Ohio.

Why is the Ohio connection important?

Because we are trying to talk to an Ohio audience and we are trying to tell people in Ohio and especially people who were not born in other countries that these (immigrants) are your neighbors. I’m with the Ohio Immigrant Alliance.

There could be other groups or other volumes outside Ohio, but this (focus) is because Ohio has a long history of being a breeding ground for white supremacist groups and there’s a lot of abuse against immigrants who are working in packing plants and on farms in Ohio. So we really wanted to focus on Ohio people to say, hey guys, these are your neighbors, these are fathers who are dropping off their kids at school in the drop-off line with you, this is the person you’re serving at the restaurant, the person next to you in a plane, so we are really focused on teaching Ohioans about their neighbors who were born in other countries.

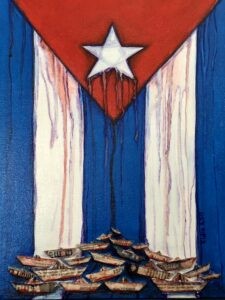

I see in the book a number of drawings, a couple of which are fish. Is there a symbolism to that?

Yes, the person who drew those paintings is from Cuba, so he’s got a huge connection to the water, and water is life. If you also notice closely, there’s a lot of references to boats and oars, too. I think Americans are familiar with people coming from Cuba and Haiti in boats and how dangerous it is, but you know people in Africa (also migrate to Europe and elsewhere on boats on the Mediterranean Sea) and are dying in the water just so they can get to a place and get a job. How sad is that!

Yes, the person who drew those paintings is from Cuba, so he’s got a huge connection to the water, and water is life. If you also notice closely, there’s a lot of references to boats and oars, too. I think Americans are familiar with people coming from Cuba and Haiti in boats and how dangerous it is, but you know people in Africa (also migrate to Europe and elsewhere on boats on the Mediterranean Sea) and are dying in the water just so they can get to a place and get a job. How sad is that!

Because we refused to have policies that allow people to migrate with dignity, they are risking their lives in these boats. I think that’s what (the artist refers to). What I took from it is how immigrants move in water, move around. I think it’s open to interpretation, but they are gorgeous pictures and beautiful.

In the afterword of the book, you said: “Sometimes the stories we tell are inaccurate. They obscure truth, recast immoral actors as heroes and manipulate thinking. This is true for much of the ‘history’ we were taught as children about the creation of the United States.” Can you elaborate on that?

Sure. I grew up in Ohio in the 1980s. In school, the history we learned was all about white man saving the world, and the genocide of native people was glossed over in such a way. So when you get older, you think, what is colonization? What happened? And then you start to realize, oh, our ancestors literally stole the land from people and then pushed them out or enslaved them or killed them.

Our education was not honest; … we were lied to and we are still lied to. And so, I think now we need to do a much better job of being more accurate about what really happened. In Ohio, unfortunately, there’s a movement against teaching (the right history) and it’s the same movement that’s everywhere, about white people who don’t want their children to feel bad about their past. But I think they should know about it. I think we should be ashamed and that’s how we learn from what happened and hopefully correct and not repeat the mistakes of the past.

“Our education was not honest; … we were lied to and we are still lied to.”

How do you rate President Joe Biden and Donald Trump in terms of immigration policy?

Oh gosh! When Trump came in, it was like a bomb went off and all of a sudden people who had lived in the United States for 30 years were being deported left and right and the decisions were so cruel and deliberate. It was truly devastating.

President Biden has not done that so much in Ohio, but he does it at the border, the southern border. They do not treat people like human beings who deserve a chance to request asylum. The most atrocious example is the way the Haitians are being treated. They are literally shipping back hundreds of people every day instead of giving them a chance to seek asylum, which our laws say we should do. So I think inside the U.S., Biden is much better, but then at the southern border, he is still using a lot of the Trump policies.

You talk passionately about immigration. What’s the motivation for you?

It started with my grandfather whose family is from Italy and he was dark skinned. I think he felt a little bit like a half cast. He taught me that that’s a situation that people feel. Back in the early 1900s, due to his dark skin, he saw a little bit of discrimination in Ohio but he ended up being fine and nothing bad ever happened to him. So that was the beginning of it.

But the most passion more recently was when I started meeting people who were in jail. I went to a small county jail in Ohio with a lawyer who was meeting with about 10 clients, and they were Muslim men from Mauritania. In this jail, there was like 99% white (people). It was in a very rural white county, an area that’s very conservative. To see the clothes they had to wear, the shoes and food (it was like dog food) … and just how they were being treated like they were members of al Qaeda.

They were just workers. They worked in factories; one was an electrician. They were good people. The only reason they were in that jail was because Trump was trying to be as mean as possible. That meeting really opened my eyes. But there was a positive to it. Those men, really what they did was, they created a protection group for themselves. They worked together to help each other and so instead of trying to compete with each other for lawyers, money or resources, they helped each other; and because they did that, there was a system created where, if someone was to be deported, they (find ways to assist the person like contacting people outside to engage a lawyer they feel could help).

The ugliness of what they were being served for food, their plastic shoes and the difficulties they had in trying to pray and things like that showed the worst of humanity on the government part and the beauty and best of humanity in people coming together to help each other.

Have you been to Africa?

No, I wanna go, but I don’t want to go to Mauritania (where, according to Saidu Sow, in Far from Their Eyes, people are discriminated against based on skin color).

Well, I invite you to visit my country Nigeria, the Giant of Africa.

I just heard this podcast by AfroBubbleGum, an art movement in Kenya. An artist from the country said (the popular theme) in Western media about Africa is famine, war, poverty but she said hey, we’ve got all these going on, we are dynamic, we are beautiful. … Yes, Nigeria is a good place and I want to go to Senegal too.

What’s your view about COVID and how it has affected lives in the last two years: the mask mandate, vaccine. What do you make of all of these?

“It’s horrible but it does really show you the two different sides of America and I see that in immigration all the time too.”

I think it’s a good example of how there are two sides to America and two sides to society. There’s the one side which is like the health care workers and food industry workers and the people who are wearing their masks all the time and getting triple vaccinated, doing that because that’s the right thing to do for the entire community.

You know we are members of a community and none of us is better than the other, but then there’s the selfish side that says I don’t wanna wear mask, I don’t want to get vaccinated, you can’t tell me what to do. I have people like that in my family, unfortunately, and I’m not talking to some of them right now because their selfishness is putting other people at risk and it’s a superiority (thing) that their life is worth more than another person’s. So, it’s horrible but it does really show you the two different sides of America and I see that in immigration all the time too, sort of like the people who are globally minded and community oriented versus people who are very selfish, self-centered.

Outside immigration matters, how do you spend your time. What are the things you like to do?

I love yoga, in the hot room, and I love to read. I do not read nonfiction. I read like thriller fiction, set in England, something that completely has nothing to do with immigration, or politics or anything serious like that. I love to read fiction.

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who currently lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.

Related articles:

Some African immigrants see their hopes of a better life in the U.S. dashed by new immigration plan

Dreamers left with disappointment once again as Senate parliamentarian dashes their hopes

Immigration advocates furious with Biden administration over Remain in Mexico policy