Divorce is never easy. Even in the most amicable partings, the division of assets causes more contention than any other irreconcilable differences. In the case of United Methodists, breaking up may be even harder to do because of the structural and legal ties that bind the worldwide denomination together.

Two concepts form the United Methodist idea of church organization. One is the concept known as “connectionalism,” and the other is the primary tool that puts connectionalism into action, the “trust clause.”

Connectionalism

John Wesley

The idea of “connexion,” to give its original British spelling, was begun by Methodism’s founder, John Wesley, as a way to support itinerant Methodist pastors. Since Methodism was originally an evangelistic reform movement and not a denomination, Methodism received no financial or vocational support from the Church of England. Thus its traveling preachers were cut off from both salary and spiritual support. The great Charles Wesley hymn And Are We Yet Alive? was written specifically to account for the fact that Methodist preachers might not make it from one yearly “connexional” gathering to the next.

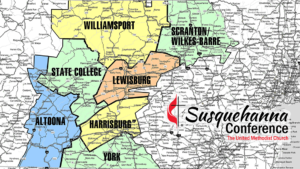

Today United Methodism’s understanding as a “connectional” church means that its congregations are organically linked to one another through a network. Unlike Baptists, Presbyterians and other congregation-based churches, the UMC has designated its regional unit known as the “annual conference” as the basic unit of the denomination. Complicating this understanding are three connotations for “annual conference.” According to the official website, UMC.org, “the annual conference is a regional body, an organizational unit AND a yearly meeting.”

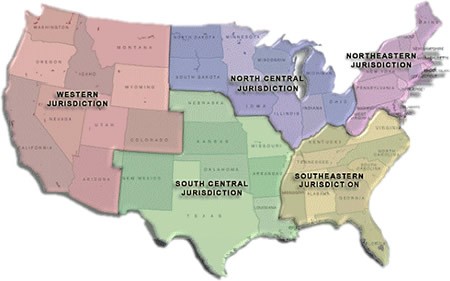

The U.S. United Methodist Church is divided into 54 annual conferences and three “missionary” conferences. The missionary conferences — Alaska, Indian Missionary in Oklahoma, and Red Bird in Kentucky — encompass geographic or cultural areas deemed unable to support themselves without funds from the entire denomination. (Alaska has petitioned to become a district of the Pacific Northwest Annual Conference, but that decision has been postponed because of rescheduling the worldwide General Conference due to the coronavirus pandemic).

U.S. conferences are supervised by 46 bishops who are assigned to areas that may include more than one conference. For example, the Oklahoma Area bishop supervises both the predominantly white Oklahoma Annual Conference and the Indigenous Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference.

U.S. conferences are supervised by 46 bishops who are assigned to areas that may include more than one conference. For example, the Oklahoma Area bishop supervises both the predominantly white Oklahoma Annual Conference and the Indigenous Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference.

Annual conference boundaries are drawn according to the number of lay members — a minimum of 100,000 — in an area, which could be “a whole state, part of a state or parts of several states,” says UMC.org. For example, there are five annual conferences in Texas:

- Texas conference, based in Houston but extending as far north as Texarkana on the Arkansas state line.

- Rio Texas, based in San Antonio and extending as far south as Brownsville on the U.S.-Mexico border.

- Central Texas, based in Fort Worth and extending south to Round Rock, about 40 miles north of Austin, the state capital.

- North Texas, based in Dallas and extending north to the Oklahoma border and northeast to Paris.

- Northwest Texas, encompassing all of West Texas from Amarillo south to its headquarters in Lubbock to the New Mexico state line.

Further complicating matters, United Methodists in El Paso are part of the New Mexico Annual Conference because the city is geographically closer to New Mexico and in the Mountain Time Zone. Likewise, the panhandle of Florida from Tallahassee west to the state line is part of the Alabama-West Florida Annual Conference.

Outside the United States, some 20 bishops supervise 75 annual conferences located in Europe, Africa and the Philippines, according to UMC.org. In the past, international annual conferences had less political clout than U.S. conferences. Power has shifted in the 21st century because international conferences, especially in Africa, are growing in membership, which gives them more delegates to the worldwide assembly that enacts church law and doctrine.

The Trust Clause

Befuddled yet? Wait, there’s more.

All United Methodist units from the smallest local congregation to the biggest church-wide agency share a tight bond, a legal construct known as the “trust clause.” Here is its definition from Paragraph 2501 of the United Methodist Book of Discipline, the collection of church law and doctrine:

All United Methodist units from the smallest local congregation to the biggest church-wide agency share a tight bond, a legal construct known as the “trust clause.” Here is its definition from Paragraph 2501 of the United Methodist Book of Discipline, the collection of church law and doctrine:

“Requirement of the Trust Clause for All Property — 1. All properties of United Methodist local churches and other United Methodist agencies and institutions are held, in trust, for the benefit of the entire denomination, and ownership and usage of church property is subject to the Discipline. This trust requirement is an essential element of the historic polity of The United Methodist Church or its predecessor denominations or communions and has been a part of the Discipline since 1797. It reflects the connectional structure of the Church by ensuring that the property will be used solely for purposes consonant with the mission of the entire denomination as set forth in the Discipline. The trust requirement is thus a fundamental expression of United Methodism whereby local churches and other agencies and institutions within the denomination are both held accountable to and benefit from their connection with the entire worldwide Church. … The trust is and always has been irrevocable (emphasis added).”

Here lies the biggest structural obstacle to United Methodist schism: If a congregation decides to leave the UMC for a new denomination, be it traditionalist, progressive or otherwise, it must pay the annual conference to claim its property. Over the past four years, only a couple dozen congregations out of some 35,000 churches worldwide have left The United Methodist Church, and each has paid a heavy price for its departure.

Paying to leave

How much a church pays to get out of the trust clause often is kept confidential according to a church policy that allows secrecy for property negotiations.

Asbury Memorial Church member Valori Armstrong and Pastor Billy Hester at the church, which recently split with the UMC. (Photo: Asbury Memorial Church)

For example, a progressive congregation in Savannah, Ga., the former Asbury United Methodist Church, officially left the denomination on Sept. 3. Church leaders there didn’t disclose the amount that the new, nondenominational Asbury Memorial Church paid to the South Georgia Annual Conference, nor did public documents of South Georgia’s Aug. 15 session specify an amount.

Typically the “disaffiliation” amount includes estimated value of the real estate, personal and intangible property, along with amounts owed for apportionments, pastors’ pensions and other debts to the annual conference.

Grandview UMC choir

In another example, a leader of Grandview UMC in Lancaster, Pa., a progressive congregation in the Eastern Pennsylvania Annual Conference which has voted to leave the UMC even before a formal split, has acknowledged that his church will pay close to $1 million for its freedom.

Legal precedents add weight to the power of the trust clause. Challenges to it thus far have failed in court. There have been cases in which a local judge sided with a congregation, but those rulings have been overturned consistently on appeal — and the annual conference always appeals. Past efforts to have General Conference ease the trust clause also have failed.

Over the half-century that United Methodists have been squabbling over the acceptance of LGBTQ people, more than one church wit has opined that “only the trust clause holds The United Methodist Church together.” Not only does the joke ring true, the trust clause forms the tightest bond that must be addressed if the UMC’s General Conference votes to divide the denomination at its 2021 session.

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

This story was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.

More by Cynthia Astle:

Is the United Methodist separation still on?

Death of a bishop, birth of a new denomination intertwined for UMC

Another United Methodist plan demands patience more than specifics

Amid its own racist history, United Methodist Church unites against racism