When family members of the Charleston Nine forgave the white supremacist who murdered their loved ones after Bible study in their church, white Christians marveled at their witness to Christian faith, holding them up as models to be followed. Although a controversial move, at its heart it was a commitment to obey the direct commandments of Jesus, those teachings found in the Gospel narratives.

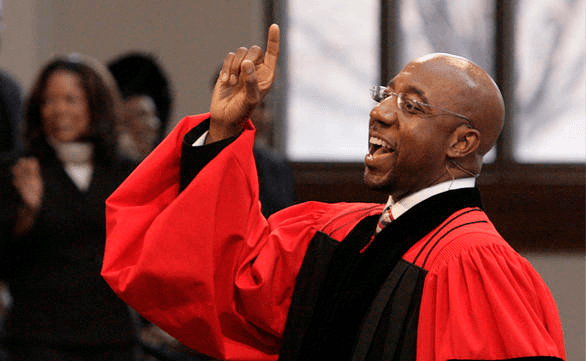

Although demonized by Raphael Warnock’s Senate opponent, this is the Black Church tradition in which Warnock was raised and in which he is now a leading pastor. It is an American tradition born from enslaved Christians reading the Bible in light of the experience of enslavement.

Jennifer McBride

Through this lens, they and their descendants came to see that the dominant theme in the Bible is deliverance, in Warnock’s words, “from the slavery of sin and the sin of slavery.” Trusting Jesus as the great liberator, pastors in this tradition proclaim that Jesus’ commands are trustworthy and realistic for both our personal and political lives.

Warnock’s politics are shaped by a lifetime of Christian discernment about what straightforward obedience to Jesus demands. What kind of political action does Jesus call us to through his commands to make peace, do justice, love enemies, welcome strangers, forgive debt, release captives, be merciful and repent from social practices that counter the reign of God?

Such serious attention to Jesus Christ characterizes the faith tradition that Warnock inherited from his ancestors, from his predecessor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, Martin Luther King Jr., and from his doctoral advisor, James Cone. It is a faith tradition that is, in Jeremiah Wright’s words, “unashamedly Black and unapologetically Christian.” It is a tradition of wisdom and action born from a particular people whose faith has a universal aim — the flourishing of every human being.

Kristopher Norris

The unapologetically Christian claim that the gospel should inform everything Christians do in their personal and public lives drives Warnock’s campaign for the U.S. Senate. It is this unapologetically Christian claim that we hope might bend the ear and capture the attention of white Christians who fill churches across Georgia. We have an opportunity to elect one of the most biblically informed, communally engaged and politically thoughtful leaders of our time. We have an opportunity to learn from, and live into, a model of Christian politics that aims not to dominate with an exclusively Christian agenda but to serve the needs of all our neighbors — and in that work, glorify God.

But, of course, we know the difficulty. The vast majority of American Christians have now so tightly aligned our faith to partisan loyalty that it is hard to untangle them. Indeed, for many it is almost impossible to imagine a different way of being a faithful Christian.

This is what Warnock’s political opponents are counting on. As Maya King claimed in Politico, “Georgia’s Senate candidate Raphael Warnock has made his faith a defining element of his candidacy. The GOP aims to make it his fatal flaw.”

“They carry on a long history of disparaging the theology of the Black Church in America.”

To this end, Kelly Loeffler has attacked Warnock as “radical” and an “extremist,” and conservative media outlets have criticized his theological mentors. In doing so they carry on a long history of disparaging the theology of the Black Church in America, a church that taught Warnock, in his words, that “the gospel is inescapably political. It requires you to take sides, especially where issues of justice and human dignity are concerned.”

In this tradition, personal spiritual formation and collective social change are linked. Both are integral to the core of the gospel message — to love your neighbor as you love yourself. If we are honest, then, perhaps the scariest thing about Warnock’s politics for white Christians like us is that they may lead to what Jesus promises: Personal and social transformation.

For this reason, the attack articles are correct in one way. Warnock is “radical” in the original and best sense of the word, that is, proceeding from the root or origin. His radicality is rooted in the identity and mission of Jesus, the one who invites us into God’s redemptive work of building a new world.

Jennifer M. McBride serves as associate dean and assistant professor of theology and ethics at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. She is author of Radical Discipleship: A Liturgical Politics of the Gospel, The Church for the World: A Theology of Public Witness, and co-editor of Bonhoeffer and King: Their Legacies and Import for Christian Social Thought. She lives in Atlanta, where she is a member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. Kristopher Norris is the visiting distinguished professor of public theology at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. He is the author of Witnessing Whiteness: Confronting White Supremacy in America’s Churches. As an ordained Baptist minister, he has written two previous books on the relationship of Christianity and politics, Kingdom Politics and Pilgrim Practices.

Related articles:

Understanding Black theology, white fragility | Greg Garrett

Why conservatives can’t get Jeremiah Wright out of their heads | Corrie Shull

In Georgia, demonizing Black Liberation Theology yet again | Steve Harmon

‘The Critique’ versus ‘The Heroic Narrative’ defines the debate in America today | Alan Bean