Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one. — John Hutchinson, 1630

John Hutchinson led a ragtag group of Puritan colonists into a deadly winter of New England discontent. But it was an experiment and new start for these hopeful refugees of British overreach.

Hutchinson’s lasting image came from Jesus and the Sermon on the Mount: a “city on a hill” that cannot be hid. We will be, he dreamed on the swaying ocean-tossed ship Arbela, a model for the world, a shining beacon for others to emulate. He liberally quoted from Galatians 6, Paul’s impassioned imperative to care for one another, to bear one another’s burdens, to work for the common good.

Portrait of John Hutchinson, 1643

And citing Micah 6:8, he extolled his Puritan travelers: “Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one.”

The balance of justice and compassion

Only then would their ship (both the Arabella and their future ship of his envisioned society) survive. Hutchinson’s vision incorporated clear compassion for all involved — the deeply spiritual Puritans as well as their largely secular escorts, the soldiers and merchants who accompanied them.

His call for justice comingled with his clear concern that each should care equally for the other. They were to be their brother and sister’s keepers. So a balance of justice and compassion were central to this new experiment on a distant shore. They were not attempting to free themselves from anything. Instead, their effort was to purify the old ways, to work harder, to be more disciplined and together create a new citizenship that would benefit all the members.

“A balance of justice and compassion were central to this new experiment on a distant shore.”

Problems would arise in this experimental balancing act, of course. Baptists, Quakers, Native Americans, Seekers and any number of other non-Puritan types generated serious problems for those in charge of regulating social behaviors. Freedom was elusive.

For these New England Puritans, this odd concept of any kind of liberty was suspect and never a priority. Freedom was indeed being experimented with; but to find the experiment in practice, one had to venture farther south.

New Amsterdam, 1624

It was a small trading post on the tip of a long island they would call Manhattan. Unconstrained by a need to regulate ethnicity or religion, the crafty Dutch and the merchants who plied their commercial trade were the richest and most successful in the world at the time. They discovered that commerce works best when traders are motivated by profit, not by petty national or religious bigotries.

The Dutch invented the stock market in 1602. The resulting commercial empire they cultivated quickly expanded. And their experiment with capital demonstrated the value of multicultural, multiethnic commercial interactions. Within a brief time, New Amsterdam and this new harbor on what would be called the Hudson River bustled with every kind of ethnicity, religion and language most Europeans had ever imagined.

“If liberty of this kind worked in the commercial world, perhaps it could work in the religious one as well.”

This was what freedom would begin to look like. It was frightening to some. But the clear commercial victories the Dutch enjoyed revealed a message that could not be ignored. Commercial freedom worked. And if liberty of this kind worked in the commercial world, perhaps it could work in the religious one as well.

When the British took over New Amsterdam in 1664 and renamed it New York, they wisely maintained the Dutch commitment to free trade, openness to new ideas and unconcern with national origins. Liberty of thought, heart and pocketbook began to take hold in a strange, unique and highly successful secular experiment that continues to thrive.

The lessons of freedom in New York and the commitment to biblical justice and compassion in New England battled with each other for most of our country’s earliest years. The tension found a new and visionary articulation coming from a highly influential voice.

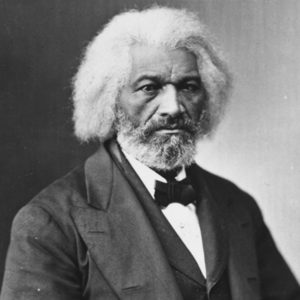

Frederick Douglass, 1867-68

Frederick Douglass preached a series of sermons in these two post-Civil War years. As a person who had escaped slavery, Douglass embodied a potent message. His intellect, experience and growing name recognition positioned his words to be heard across the bounds of race, class and geography.

Frederick Douglass

He crossed the country to bring healing to a land still ravaged by horrible wounds, young men scarred for life, families torn asunder by poverty, loss and grief. But even more, his was a titillating challenge.

These sermons of 1867-68 cast a broad and lasting vision. He artfully alludes to Hutchinson, a city on a hill and the caring for one another in Galatians 6. He then creatively combines this biblical imperative with the secular discoveries begun in New Amsterdam and adapted in New York. Intrinsic equality and helpful mutuality should be the order of the land. Justice and compassion should balance the freedom, or the rational liberty we crave.

He said:

In whatever else other nations may have been great and grand, our greatness and grandeur will be found in the faithful application of the principle of perfect civil equality to the people of all races and of all creeds, and to those of no creeds. We are not only bound to this position by our organic structure and by our revolutionary antecedents, but by the genius of our people. Gathered here, from all quarters of the globe by a common aspiration for rational liberty as against caste, divine right governments and privileged classes, it would be unwise to be found fighting against ourselves and among ourselves; it would be madness to set up any one race above another, or one religion above another, or proscribe any on account of race, color or creed.

“The lasting brilliance of his words echoes still among our daily debates.”

The lasting brilliance of his words echoes still among our daily debates. How equal are we? How much common ground can we find? We continue to live in the tense balancing act of freedom, justice and compassion Douglass casts before us?

And he would not be alone.

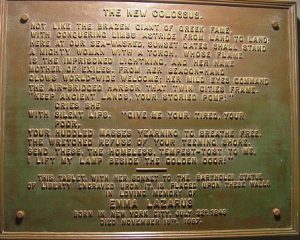

Emma Lazarus and The New Colossus, 1883

Emma Lazarus grew up in New York City, the daughter of immigrants, a Jewish woman ministering to Jewish refugees. They came to this harbor on the Hudson fleeing the pogroms of Russia, Poland and Eastern Europe. Watching them arrive with nothing, many sick and malnourished, Emma Lazarus witnessed the tragedy of poverty and the travesty of prejudice.

She also saw in these survivors of genocide and ethnic cleansing a compelling resiliency. She wrote a poem, words inspired by these irrepressible men and women rising from their wounds to generate new energy in her native city. Her words speak still from the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

She also saw in these survivors of genocide and ethnic cleansing a compelling resiliency. She wrote a poem, words inspired by these irrepressible men and women rising from their wounds to generate new energy in her native city. Her words speak still from the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Notice how the vision of Hutchinson, the mutuality of Galatians, the vibrancy of New York, the equitable and colorblind calling of Douglass coalesce in the compassionate, welcoming justice of Lazarus all “yearning to breathe free.”

Still, there is more.

Katherine Lee Bates and Pike’s Peak, 1893

Katherine Lee Bates taught English at Wellesley College. She was a single woman struggling for recognition and tenure. She was battling the consistent tides of prejudice because of her giftedness and gender. And in 1893 she took a vacation to the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. There, she found inspiration at the summit of Pike’s Peak.

She titled the resulting poem by that name. But later, she and others realized her lyrics captured a far larger vision. The poem Pike’s Peak became America the Beautiful.

O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountains majesties,

Above thy fruited plain.

America, America

God shed his grace on thee

And crown thy good with brotherhood

From sea to shining sea.

O beautiful for heroes proved in liberating strife,

Who more than self their country loved

And mercy more than life!

America, America, may God thy gold refine

’Til all success be nobleness

And every gain divine!

Katherine Bates’ inspired words rekindle every heart with a hopeful vision of providence. She lived for years as a single woman, a professor committed to the craft of writing, to the call of teaching and to the need of social reform.

She also was devoted to her roommate, a woman she loved with passion and deep loyalty. She never could acknowledge their mutual love publicly. But her letters reveal decades of faithfulness that today would allow us to celebrate her affiliation with the LGBTQ community. Her descriptive lyrics in America articulate the delicate balancing act so painstakingly raised over the centuries.

“Through ebbs of hubris and occasional flows wisdom, our continued storm-tossed American identity debate rages.”

Through ebbs of hubris and occasional flows wisdom, our continued storm-tossed American identity debate rages. Battle lines have been forming for decades. Anger seems to overwhelm us. But we can again shape a judicious path through our current discontent.

With these wise voices of our past, we still can forge more lasting and respectful bonds. Our visions differ. But our calling remains. Hutchinson, Douglass, Lazarus and Bates all speak with one clear American voice, one calling in balanced tones of equal and highly biblical measures: Freedom, justice and compassion sensibly balanced for all.

May it be so now, and for our future together.

David Jordan serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Decatur, Ga.

Related articles:

Hope for a new year out of the historical disunity of our United States | Opinion by David Jordan

John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and necessary grace | Opinion by David Jordan