The horror of death and destruction now crippling the Middle East, euphemistically known as “The Holy Land,” finds me constantly defaulting to one overriding emotion: Gratitude.

And no, that is not a typo. I’m grateful my late sister, Nancie Wingo, did not live to witness the betrayal of all she lived for in the 33 years she served as an English teacher at the Beirut Baptist School and later at the Baptist Hospital in Gaza City, under appointment of the Southern Baptist Foreign Mission Board.

The possibility of living with physical danger in the Middle East has existed for decades, and Nancie was not immune to its challenges. Her school and apartment were in the heart of the Muslim sector of the city, and at one point during the 15-year civil war, which took the lives of 150,000 Lebanese, her sixth-floor apartment took a direct rocket hit, blowing away her terrace, leaving a gaping hole in her living room wall while she and her neighbors had taken shelter through the night in the building’s basement.

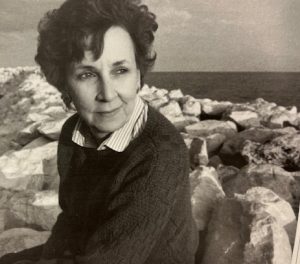

Nancie Wingo on her bombed-out balcony

Nancie’s response on seeing the hole in her living room wall was that she almost hoped it would not be repaired because “it opened up a beautiful view of the Mediterranean.”

All through this period, students often were unable to move safely from their homes to reach the school compound. But each time they returned, Nancie marveled at how they greeted her with the words, “Inshallah, Miss Wingo, God protected us and allowed us to come back safely.”

Their feeling that God had protected them when they were most afraid was an epiphany for Nancie, who later said, “I owe these students a great debt for showing me how God is at work bringing goodness into their lives. I felt a renewed gratitude for his love everywhere I experienced it.”

The school of 900 students was 70% Muslim and although her Muslim students and Muslim neighbors followed a different path to God, Nancie could not avoid respecting their path, saying only that she knew it was her job to reflect God’s love as she understood it and that whatever path God chose to dispense that love was not her decision to make. However heretical that may sound to some Christians, Nancie learned through her own lived experience that any resistance to confessing Jesus as Lord that puts nontakers outside the reach of God’s grace is an act of theological hubris well beyond any human’s pay grade.

And this seems as good a place as any to say that everything about the fervent attempt by Christian nationalists in the United States aimed at forcing an entire population to bow before their certainty about what God really has in mind for America is as big a threat to American freedom as Hamas is to Gaza or Hezbollah is to Lebanon.

Nancie Wingo teaching

Her daily encounters with her students were the beginning of Nancie’s understanding that all religious identity is an accident of birth. A child born in Tripoli is as likely to be a Muslim as a child born in Texas is likely to be a Christian — or even Baptist.

It took nothing away from Nancie’s belief that God was reflected most fully in the life of Jesus for her to also see God was fully real in the lives of her students and Muslim friends. “Who am I?” she often asked, “to tell these people they have it all wrong?”

Her Muslim students and neighbors repeatedly told her of their great respect for Jesus as a prophet, while acknowledging they could not accept him as God in human flesh.

As the long civil war intensified, Nancie became the last American still living in West Beirut (operation of the school already had been turned over to Lebanese Baptists) and in February 1987 she was ordered by the U.S. Embassy to leave the city’s Muslin sector within 12 hours because they no longer could offer her any protection. She was put on a boat to Cyprus, where she met Baptist missionaries from the Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza, still known as the Baptist Hospital of Gaza although it is currently under Anglican management.

Nancie Wingo in 1987 in Cypress, looking back toward Beirut.

Knowing she would not be able to return to her beloved Beirut any time in the foreseeable future, Nancie agreed to join the Gaza hospital staff as an English teacher to the hospital’s nursing students. She got there just in time to witness the outbreak of the Intifada uprisings, which led to frequent emergency evacuations through underground tunnels in southern Gaza to reach the relative safety of Egypt.

Last year, the Al-Ahli Hospital was the scene of one the fiercest attacks following Israel’s invasion of Gaza. Palestinian authorities reported deaths of more than a hundred men, women and children who had sought shelter inside the hospital’s walled compound.

In Gaza, Nancie’s job was to help young nursing students improve their English fluency, which could lead to good nursing jobs throughout the Middle East and even in Europe. Most of the students came from the nearby Jabalia United Nations Refugee Resettlement Center, whose population included 100,000 Palestinians living in extreme poverty with no clean water and open sewage lines.

Nancie often visited the students and their families at the center, where she heard over and over how the parents considered these students the only bright hope in their lives. When Israeli forces moved into Gaza after the October 7 attack by Hamas, the refugee camp was reduced to rubble.

After her retirement in 1997, Nancie returned to her home in Fort Worth, Texas, where she found comfort and endorsement from her home church, Broadway Baptist. She served as a deacon for several years prior to her death on Christmas Eve 2016.

Nancie Wingo

Nancie never for a moment abandoned the promise of the faith she held, but she understood clearly how religion is the epicenter in the Middle East for virtually everything tearing it apart. Christians, Muslims and Jews all have their own agenda on how to make the area safer, and none of them agree.

There never be will peace in the Middle East until peace in the Middle East is the No. 1 priority for everyone living there. For now, it is not even on their radar and any such talk would require radical changes from all three faiths.

The Jews, the Muslims and the Christians would have to agree that it is better to live in peace and security as neighbors with religious differences than as neighbors who hate and fear each other.

All the options for achieving peace require difficult decisions no one is willing to talk about:

- Israel must stop claiming its land was given by God to their ancient ancestors. God did not create the state of Israel in 1948. The act came from the very human body of the United Nations in the greatest single act in its history. Israel must redraw its borders to the terms of the U.N. creation agreement and cease its expansion into the occupied West Bank.

- Muslims must accept that Israel is in the Middle East to stay, in return for recognition of a secure and independent Palestinian state among the other countries of the region. Donald Trump’s U.S. election victory only hardens the Israeli resistance to any kind of compromise in pursuit of peace with its neighbors.

- Christians must stop telling both of them all they really need is Jesus. The world does not need another Christian Crusade.

Only then will the Middle East earn the right to be called the Holy Land. In her own small way, Nancie modeled this possibility during her long years in Lebanon and Gaza so no one gets to blow this off as a pipe dream.

Will it ever happen more broadly across these violently conflicted populations? Probably not. Living in peace with their neighbors never has gotten much traction at the highest levels in the area, and the savagery of war in the Middle East continues as if fighting is what matters most to them.

My gratitude is that Nancie cannot see this murderous assault on the noblest purpose of her life.

Hal Wingo

Hal Wingo is a 1957 graduate of Baylor University who later served as a Baylor regent for nine years. He began a career with Time Inc. in 1963 as a national correspondent based in Los Angeles before becoming Far East regional editor for LIFE magazine in 1968, responsible for LIFE’s coverage of the Vietnam War. He returned to New York in 1970 as a senior editor and was part of the team that created People magazine in 1974. He served as People’s assistant managing editor and international editor until retirement in 1995, and was a founding board member of Associated Baptist Press, now Baptist News Global. He and his wife, Paula, live in Rancho Mirage, Calif.