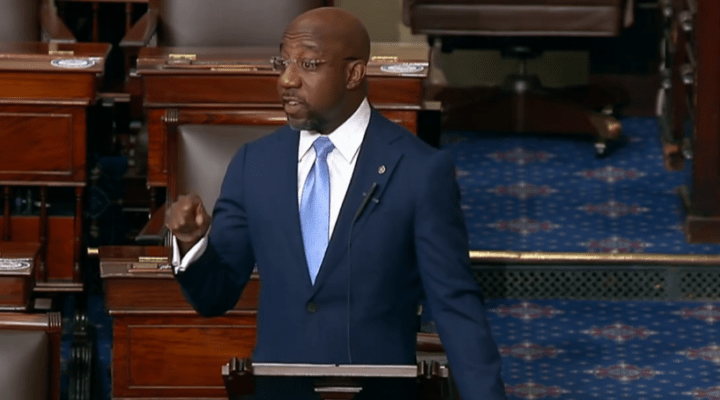

A vote is “a kind of prayer,” Baptist pastor Raphael Warnock said in his first speech on the Senate floor as a newly elected legislator.

The March 17 speech was a blistering call to protect voting rights and a critique of Republicans in his home state of Georgia who are promoting new legislation to limit access to the ballot — efforts sparked by Warnock’s own victory as a Democrat in a January runoff election in a state previously considered reliably Republican.

“As a man of faith,” he added, “I believe that democracy is the political enactment of a spiritual idea — the sacred worth of all human beings, the notion that we all have within us a spark of the divine and a right to participate in the shaping of our destiny.”

He paraphrased 20th century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr to affirm: “Humanity’s capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but humanity’s inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.”

Souls to the Polls

Warnock’s Atlanta congregation, Ebenezer Baptist Church, is one of many Black congregations that traditionally participates in a get-out-the-vote effort called “Souls to the Polls,” he noted.

Congressman John Lewis

“I was honored on a few occasions to stand with our hero and my parishioner, John Lewis. … On more than one occasion, we boarded buses together after Sunday church services as part of our Souls to the Polls program, encouraging the Ebenezer church family and communities of faith to participate in the democratic process.”

But that effort to highlight citizenship as a spiritual duty now is under attack from Republicans in Georgia and beyond, Warnock charged. “Now, just a few months after Congressman Lewis’s death, there are those in the Georgia Legislature, some who even dare to praise his name, that are now trying to get rid of Sunday Souls to the Polls, making it a crime for people who pray together to get on a bus together in order to vote together. I think that’s wrong.”

He added: “Matter of fact, I think that a vote is a kind of prayer for the kind of world we desire for ourselves and for our children. And our prayers are stronger when we pray together.”

Warnock noted that both he and Sen. John Ossoff, who is Jewish, were elected from Georgia with record voter turnout.

“But then, what happened? Some politicians did not approve of the choice made by the majority of voters in a hard-fought election in which each side got the chance to make its case to the voters,” Warnock said. “And rather than adjusting their agenda, rather than changing their message, they are busy trying to change the rules. We are witnessing right now a massive and unabashed assault on voting rights unlike anything we’ve ever seen since the Jim Crow era. This is Jim Crow in new clothes.”

“We are witnessing right now a massive and unabashed assault on voting rights unlike anything we’ve ever seen since the Jim Crow era.”

‘Voter suppression’

Since the January run-off election, 250 “voter suppression” bills have been introduced in state legislatures across the country, he said. And all use “the big lie of voter fraud as a pretext for voter suppression, the same big lie that led to a violent insurrection on this very Capitol — the day after my election.

“Within 24 hours, we elected Georgia’s first African American and Jewish senator, and, hours later, the Capitol was assaulted. We see in just a few precious hours the tension very much alive in the soul of America. And the question before all of us at every moment is: What will we do to push us in the right direction?”

In Georgia, new legislation not only would make it harder to vote, it would criminalize sharing food or water with people standing in line to vote — a kind of election-day ministry often embraced by churches.

Raphael Warnock

Despite previous efforts to suppress the vote, Georgians in November and January could not be deterred, Warnock said. “Georgia citizens and citizens across our country braved the heat and the cold and the rain, some standing in line for five hours, six hours, 10 hours, just to exercise their constitutional right to vote — young people, old people, sick people, working people, already underpaid, forced to lose wages, to pay a kind of poll tax while standing in line to vote.

“And how did some politicians respond? Well, they are trying to make it a crime to give people water and a snack as they wait in lines that are obviously being made longer by their draconian actions. Think about that. Think about that. They are the ones making the lines longer, through these draconian actions. And then they want to make it a crime to bring grandma some water while she’s waiting in a line that they’re making longer.”

This, he charged, is “democracy in reverse.”

A sign of hope

There is hope, though, Warnock said, citing his own improbable election as evidence. “In a word, I am Georgia, a living example and embodiment of its history and its hope, of its pain and promise, the brutality and possibility.”

At the time of his birth, Warnock said, Georgia’s two senators were Richard B. Russell and Herman E. Talmadge, “both arch-segregationists and unabashed adversaries of the Civil Rights Movement.” Yet today, Warnock — a Black man — holds the seat formerly held by Talmadge.

“History vindicated the movement that sought to bring us closer to our ideals, to lengthen and strengthen the cords of our democracy.”

“History vindicated the movement that sought to bring us closer to our ideals, to lengthen and strengthen the cords of our democracy,” he said.

Looking ahead to 2022

In the January runoff, Warnock defeated Republican Kelly Loeffler to serve out the rest of an open term, meaning he will appear on the ballot again in 2022 — much sooner than the normal six-year cycle for senators.

A report released March 9 by the Georgia Republican Party outlined a set of recommendations for reforming the state’s election processes. Those recommendation include ending no-excuse absentee ballots, barring third-party groups and state and local officials from sending absentee ballot request forms to voters and stopping automatic voter registration.

“The 2020 election revealed dramatic weaknesses in Georgia’s system for conducting elections, and as a result, public confidence in the integrity of that system has been shattered,” the report claims. “Public confidence cannot be restored by pretending that these weaknesses do not exist. A problem must first be recognized before it can be solved.”

The complaints about election integrity in Georgia largely follow the now-debunked claims of voter fraud alleged by former President Donald Trump, who also lost Georgia in the 2020 presidential election — a fact he has yet to acknowledge.

Related articles:

‘All Souls to the Polls’ engages churches to make voting fun and accessible

Voting rights and the people who died for them: Jonathan Daniels et al. | Opinion by Bill Leonard