I was raised in a brown evangelical church in a small, predominantly white town in central Texas. Our “mother” church was one of the many First Baptist Churches in the Texas Bible Belt. Our congregation was composed mainly of poor, uneducated, largely undocumented migrants from rural Mexico. And while we were a brown church, the Jesus we worshiped was white.

I was raised in a brown evangelical church in a small, predominantly white town in central Texas. Our “mother” church was one of the many First Baptist Churches in the Texas Bible Belt. Our congregation was composed mainly of poor, uneducated, largely undocumented migrants from rural Mexico. And while we were a brown church, the Jesus we worshiped was white.

In fact, the only image of Jesus I ever saw as a child was white. In one Sunday school lesson after another, for 18 years, Jesus was as white as the sky was blue. Normalizing Jesus as white in Sunday school literature perpetuates a twisted gospel of white supremacy, wounding the most vulnerable of God’s creation — children. In my tender mind, God was an amalgamation of all of the white versions I had seen of him in stained glass windows, movies, children’s books, evangelical tracts, etc. I was terrified of white God the Father — he was a white Thor ready to strike lightning at me at the first indication that I had sinned.

I desperately sought the love of white Jesus. While I loved him fiercely and unconditionally — the way children love — I often wept at night in secret because I was convinced that white Jesus did not and would not ever love me. I was right.

A white Jesus is a false idol.

A white Jesus can’t save a brown child.

And a white Jesus couldn’t save me. Whiteness made Jesus oppressive. Because whiteness meant oppression, and in this community, brownness was the target of oppression. Small Town was a microcosm of America.

All of the white Baptists in my life participated — consciously or unconsciously and individually or collectively — in the oppression of my people.

The white Baptists worshiped their white Jesus in a beautiful brick building worthy of their whiteness. We worshiped in an old, ugly, mold-infested building where something-was-always-broken-and-nothing-ever-worked. That building the white Baptists had “generously” purchased for us from the white Lutherans. It perfectly suited the white Baptists’ perception of us second-class brown folk.

I remember the white man, a member of FBC, who for years hired several of the undocumented families of my church, paying them meager salaries and subjecting them to degraded living conditions under the pretense of proffering employment. He participated in the systemic dehumanization of Mexican bodies — he valued brown labor, but not brown lives.

I remember the erratic white woman who showed up spontaneously one Wednesday evening during prayer service with a van of “rebellious” brown teenagers she was trying to “save.” Taking up the white man’s burden, she tried converting them first at the white church, but the white Baptists kicked the teenagers out of their church for being too “rowdy.” So she bulldozed her way into our community and our church, assuming she knew best how to “minister” to these brown children.

These white members of FBC were not acting in a vacuum. Their behavior aligned with the racist ideology of their church. Never have I heard a sermon in a white church dedicated to the denunciation of white supremacy. The one place in America that most obstinately refuses to address racism is the white pulpit.

White Baptists exuded white privilege, a privilege that shielded them from any knowledge of the raids, detentions, and deportations of members of our community and congregation. As a poor brown girl, I lacked that privilege.

We lived in the parsonage on the same block as our run-down church building. Next to our church was a wire hanger factory that radiated a noxious, carcinogenic stench that I became inured to and could only detect after I left home and encountered it again after a long trip. Hermana Rosa worked there, and on Wednesdays after her shift, she would faithfully walk over for prayer service in her uniform, reeking of the permanent stench of the sweat of oppression. She tried to deflect the awful odor by sitting in the back pew, probably unaware that she had absorbed only a bit more of it than the rest of us. We all smelled the same.

Many of the people who worked at the factory were undocumented migrants and members of our congregation. INS (what is now ICE) raided the factory, terrorizing our community. The Sunday morning after the raids, as members of our congregation tried to cope with the trauma of the raids, many people would stand up to share their testimonios, and as a church, we would call upon God to deliver us from the raids and the evils of racism. I remember their stories and prayers, stories the white Baptists never heard and prayers they never had to pray. They never had to mourn the deportation of a loved one, the separation of a mother from her child.

I prayed religiously as a child. I prayed for the people I loved by name. And when I prayed for the deported and their families, I was forced to pray to a white Jesus, the Jesus of a people who upheld a racist and inhumane system. I thus empowered my oppressor. Little me had no chance at liberation.

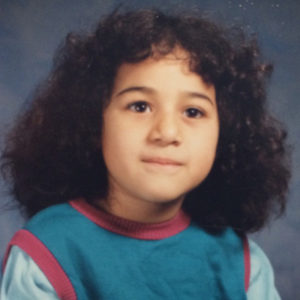

I weep for my little self, and God weeps with me. I was wounded as a child by a collective of white people who ardently preached a Jesus that could not save me.

A white Jesus is inherently a racist Jesus, and a racist Jesus saves only white people.

A white Jesus can’t save a brown child, and a Jesus that can’t save all, liberate all, and redeem all is no Jesus at all.

The white man can keep his white Jesus. I claim the Divine as mine.

Related opinion: