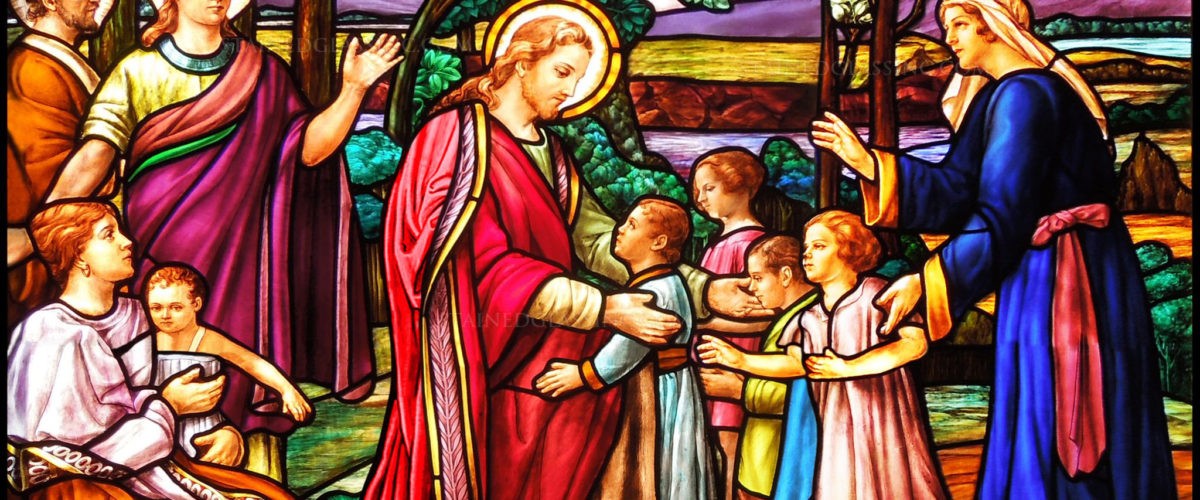

I was young — perhaps only 3 or 4 — when I learned in Sunday school that “Jesus loves the little children, all the children of the world; red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight. Jesus loves the little children of the world.”

I saw artists’ renditions of those children — little Black faces, brown faces, red faces, and yellow faces — peering out from Sunday school workbooks, but to me, those children were theoretical. I had never met anyone who was not white.

Richard T. Hughes

And I knew from the pictures in our Sunday school books that Jesus was white as well.

Then, in second or third grade, I learned to recite the American Creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident — that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

To my young mind, the American Creed was but an extension of the Christian affirmation that “Jesus loves all the children of the world,” and I knew from an early age that a white Jesus had validated the goals of my nation, the meaning of my world.

Six Great American Myths

In this way I learned the first of the six Great American Myths: that America is a Christian Nation.

A “myth” is a story, whether true or false, that gives our lives meaning, and I found great meaning and comfort in the notion that the American nation was built on the solid rock of Jesus himself.

During my teenage years, I encountered more of the Great American Myths. No one taught me those myths. Rather, they belonged to the culture in which I matured, and I absorbed them by osmosis.

I learned that the United States is a Chosen Nation, singled out by God for a special mission in the world.

I learned that the United States is Nature’s Nation, rooted in the natural order of things. While other nations conformed to human wit and contrivance, my nation conformed to God’s own design.

I learned that the United States is a Millennial Nation, destined to bless the earth with democracy and freedom and finally to create — with the help of God Almighty — a golden age for all humankind.

And I learned that the nobility of our cause — to extend freedom around the globe — rendered the United States a perpetually Innocent Nation.

When the bubble burst

But the tumult of the 1960s began to burst my mythic bubble. I listened closely as a loud chorus of voices — perhaps half the nation or more — clung to the Great American Myths even as they besmirched the name of Martin Luther King Jr., castigated the Freedom Movement as Communist-inspired and anti-Christian, and defended a war that King claimed in 1967 had “killed a million (Vietnamese) — mostly children.”

Was this what it meant to be a Christian nation? To be a nation chosen by God to bring freedom and democracy to all humankind? To be a nation built on nature’s own design?

“How could the American nation cling to the myth of innocence in the face of its long history of racial oppression?”

How, I wondered, could the American nation cling to the myth of innocence in the face of its long history of racial oppression, practiced and defended even at the height of the Freedom Movement? And how could we claim our innocence in the face of the war we were waging — and the atrocities we were committing — half a world away? These were the troubling questions that faced me down, day after day after day.

In raising these questions, I was not alone, for these were the questions that drove a wedge through the American nation in the 1960s and 1970s, creating a chasm comparable to the great divide we experience as the nation now prepares to elect a president of the United States.

I pondered those questions for some 30 years and in 2003, I wrote a book called Myths America Lives By. Even then, however, my understanding of the Great American Myths was inadequate and incomplete, although I failed to grasp that fact at the time.

The sixth Great Myth

“Professor,” he said, “you left out the most important of all the American myths.”

Fast forward to 2012 when I delivered a lecture on the Great American Myths at a professional meeting. When I finished my remarks, a distinguished Black scholar — the late James Noel of San Francisco Theological Seminary — spoke 12 words that changed my life. “Professor,” he said, “you left out the most important of all the American myths.”

“And what did I leave out?” I inquired.

“You left out the myth of white supremacy,” Noel responded.

Really? I wondered. White supremacy? The most important of all the American myths? But as I began to reflect on what Noel had said, I began to see his point. I began to see that throughout American history, the chief function of the other myths — Chosen Nation, Christian Nation, Nature’s Nation, Millennial Nation, and Innocent Nation — was to validate the moral rectitude of white America, even as I learned as a child that a white Jesus had ratified the American Creed.

In 2018, thanks to James Noel, who challenged me to think more deeply, the University of Illinois Press published a thoroughly revised second edition of my book under the title, Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories that Give Us Meaning.

It seems clear to me now, in theory at least, that some of the myths could conceivably support and sustain the richest meaning of the Creed — that all human beings are created equal and entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

“The myth of white supremacy and the myth of American innocence are worse than useless since, as outright lies …”

It also seems clear that two of the myths — the myth of white supremacy and the myth of American innocence — are worse than useless since, as outright lies, they inevitably undermine the noblest ideals of the American nation.

But those are precisely the myths invoked by people who define the nation in the constricted terms of race, religion, gender, class and social standing.

Seen in that light, our current political chasm is not just a divide between liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, or red states and blue. At its core, that divide — that gaping chasm — has exposed a massive wedge driven into the heart of the nation, a wedge between those who read the Creed in light of the myths and those who read the myths in light of the Creed.

The former agree that all are created equal so long as they are white, straight, Christian, born in the United States, and at least middle class. The latter agree with Langston Hughes that, with hard and diligent work, the United States might well

be America again —

The land that never has been yet —

And yet must be — the land where every man is free …

O, yes, I say it plain.

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath —

America will be!

Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death,

The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies,

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers,

The mountains and the endless plain —

All, all the stretch of these great green states —

And make America again!

For Langston Hughes, and for Americans today, our most important task is the redemption of the American Creed. We cannot dispense with the myths. They are too deeply embedded in our common culture to even consider that option. But we can rethink them in ways that might sustain the promise of this land, the promise embodied in our national Creed.

Richard T. Hughes is distinguished professor emeritus at both Pepperdine University and Messiah College and the author of Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories that Give Us Meaning.