When you begin a conversation about poverty by caricaturing poor people, you’ve already corrupted the discussion, particularly if beating up on the poor was your primary intent. In 1882, Russell Conwell, Baptist pastor and Temple University founder, did just that in “Acres of Diamonds,” a “sermon” he claimed to have preached over 6,000 times. Conwell declared:

When you begin a conversation about poverty by caricaturing poor people, you’ve already corrupted the discussion, particularly if beating up on the poor was your primary intent. In 1882, Russell Conwell, Baptist pastor and Temple University founder, did just that in “Acres of Diamonds,” a “sermon” he claimed to have preached over 6,000 times. Conwell declared:

“Let me say here clearly … ninety-eight out of one hundred of the rich men of America are honest. That is why they are rich. … That is why they carry on great enterprises and find plenty of people to work with them. … I sympathize with the poor, but the number of poor who are to be sympathized with is very small. To sympathize with a man whom God has punished for his sins … is to do wrong. … Let us remember there is not a poor person in the United States who was not made poor by his own shortcomings.”

In late 2017, two U.S. senators, Conwell’s rhetorical descendants, pontificated similarly about government funding for poor people, including impoverished children. In a Nov. 29 interview, Sen. Chuck Grassley expressed his support for cutting the estate tax, a tariff effecting only 0.2 percent of Americans, for reasons he called both philosophical and practical: “I think not having the estate tax recognizes the people that are investing, as opposed to those that are just spending every darn penny they have, whether it’s on booze or women or movies.”

Leaving no crassness unturned, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, commenting on pending cessation of government funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), reminded critics that while he helped establish the CHIP program, and believed it would be refunded, nonetheless, “the reason CHIP’s having trouble is because we don’t have money anymore.”

Hatch continued: “I happen to think CHIP has done a terrific job for people who really needed the help. I’ve taken the position here for my whole Senate service: I believe in helping those who cannot help themselves but would if they could. I have a rough time wanting to spend billions and billions and trillions of dollars to help people who won’t help themselves — won’t lift a finger — and expect the federal government to do everything.”

Hatch faulted “liberal philosophy” for creating “millions of people … who believe everything they ever are or hope to be depends upon the federal government rather than the opportunities that this great country grants them. And I’ve got to say, I think it’s pretty hard to argue against these comments.”

Actually, it’s not all hard to argue with the senator’s judgments. Yes, there are people who take advantage of government “welfare” in many forms. But if Hatch wanted to make a collective ethical assertion, he might have moralized about rich people as well, folks prepared to reap huge benefits from new legislation that enhances their ability to clip their tax-exempt-stock-coupons without “lifting a finger.” Caricature masquerading as moral imperative might at least be egalitarian!

To parody low income, impoverished people politically, ecclesiastically, theologically or pragmatically is to undermine or downright ignore the almost relentless concern offered them by the purported Good News of Christ’s gospel, especially at the season of Advent.

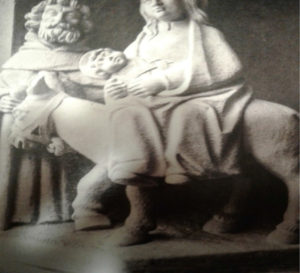

The Jesus Story begins as a pregnant Virgin sings about justice for the poor and humiliation for the rich. The Bethlehem journey occurs because of mandated Roman taxation. The Word made flesh is cradled in a feed trough and makeshift homeless shelter because there was “no room for them in the inn.” Shepherds, whom Joachim Jeremias described as “despised in everyday life,” received the first public broadcast of Immanuel’s birth. And no sooner had Mary’s water broken than she, Joseph and the babe, the One who’s first sermon begins, “The spirit of the Lord has anointed me to preach good news to the poor,” became refugees, escaping the genocidal mendacity of a narcissistic, self-indulgent monarch.

Beeson Divinity School’s annual Christmas card includes Dean Timothy George’s photo of “The Flight into Egypt” and Malcom Guite’s powerful poem, “Refugee”:

We think of him as safe beneath the steeple, Or cosy in a crib beside the font,

We think of him as safe beneath the steeple, Or cosy in a crib beside the font,

But he is with a million displaced people

On the long road of weariness and want.

For even as we sing our final carol

His family is up and on the road,

Fleeing the wrath of someone else’s quarrel,

Glancing behind and shouldering their load.

Whilst Herod rages still from his dark tower

Christ clings to Mary, fingers tightly curled,

The lambs are slaughtered by the men of power,

And death squads spread their curse across the world.

But every Herod dies, and comes alone

To stand before the Lamb upon the throne.

We can’t be sure how the “Christmas-present tax-cut” passed by the likes of Grassley and Hatch will work itself hence in American society, but based on what little we know it could easily reverse the Lukan words of Mary: “The wealthy have been filled with good things; the poor sent away empty.”

As Advent turns to Christmas, let’s reclaim its calling to bring “good news to the poor,” “the least of these” — hungry or thirsty, homeless or imprisoned, lined up in the ER or at the stop light with cardboard signs. The Rev. John Bost, a Winston-Salem, N.C., friend and Holy Ghost-baptized Pentecostal, echoes this on his Facebook page:

As I reread the Good Samaritan story in Luke 10:30-36, my mind goes to the persons I pass each day begging on the street corners. Were it evident that a citizen had been beaten down by a criminal, left bloodied on that same corner, I would run to him/her, call 911, offer interim aid and then follow up as he/she recovered.

Yet when a long term generational poverty beats one down, steals any opportunity (boot straps), though less bloodied but equally immobilized, apparently homeless and virtually helpless, I simply avoid eye contact, assume the worst about that particular human being and continue my shopping … ignoring my neighbor!

Bethlehem was the Cosmic Christ getting out of his car long enough to administer mercy on the “street corner” where we were once begging!

Advent and Incarnation, then and now. Good news to the poor doesn’t trickle down. It overflows.