In a nation where the 1611 King James Version of the Bible still holds tremendous sway, imagine the challenges of updating one of the modern English translations of the Good Book.

That’s why Friendship Press, the National Council of Churches and the Society for Biblical Literature assembled a team of dozens of scholars to undertake the first update of the New Revised Standard Version in 30 years.

The New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition, also known as NRSVue, currently is available for digital download and will be published in printed copies later this spring. The update is significant, in part, because the NRSV is a preferred translation for many biblical scholars, seminaries, and mainline and progressive Protestant churches.

While the project’s organizers cite many reasons for tackling an update, users of the translation may be intently interested in two things: Gender usage and how difficult passages related to homosexuality are rendered.

While the project’s organizers cite many reasons for tackling an update, users of the translation may be intently interested in two things: Gender usage and how difficult passages related to homosexuality are rendered.

Yet the most significant changes are more likely to be found in Old Testament texts rather than New Testament texts. This is due to the primary underlying motivation for the update.

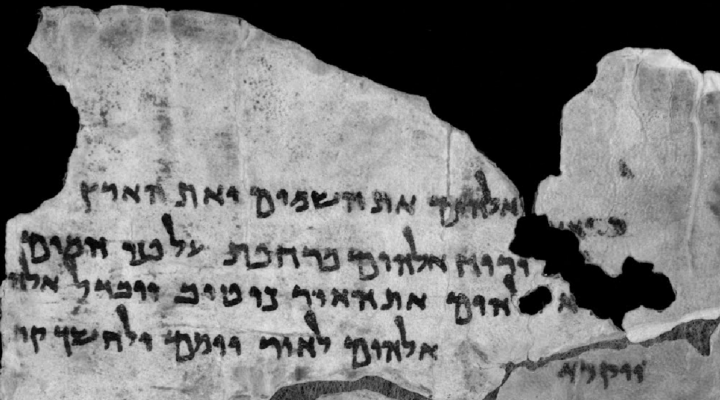

The Dead Sea Scrolls

An information page on the website of Friendship Press explains: “The primary focus of the 30-year review is on new text-critical and philological considerations that affect the English translation. The publication of the majority of Judaean Desert biblical texts and fragments has led to a revolution in understanding readings that differ from medieval Hebrew traditions in the Masoretic Text, which was the basis of the New Revised Standard Version.”

That’s a reference to the Dead Sea Scrolls, ancient manuscripts discovered between 1947 and 1956 in caves near Khirbet Qumran, on the northwestern shores of the Dead Sea. The scrolls are about 2,000 years old and date from the third century BCE to the first century CE.

The scrolls actually are fragments of scrolls scholars reconstructed from 950 manuscripts. The fragments include portions of 200 copies of various books of the Hebrew Bible, known to Christians as the Old Testament, as well as apocryphal and sectarian texts.

According to the Israel Museum, where many of the scrolls and fragments are now housed, the texts represent “the earliest evidence for the biblical text in the world.” No original manuscripts exist for any of the 66 books of the Bible; today’s Jewish and Christian Scriptures are based on copies of copies of copies, then translated into various modern languages such as English.

Today’s Jewish and Christian Scriptures are based on copies of copies of copies, then translated into various modern languages such as English.

After decades of work on the scrolls and seeking to understand their dating and sourcing, scholars now are working to incorporate what they’ve learned into modern translations of holy Scriptures. Thus, the importance of the Old Testament review to the overall NRSV update.

How to eat an elephant

Tackling a revision to a translation of the entire Bible is somewhat like the old joke that asks, “How do you eat an elephant?” The answer: “One bite at a time.”

To that end, organizers of the NRSV project assigned editors to each of the Bible’s 66 books. Those editors, and others working with them, made suggestions for updates where needed within their assigned areas. Those edits then were accepted, rejected or further edited by the editorial board.

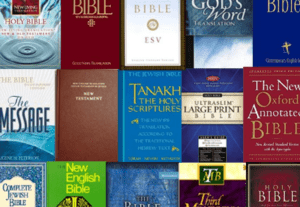

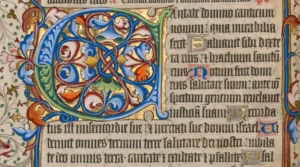

A page from the Abbey Bible, created in the mid-1200s for a Dominican monastery. Considered one of the earliest and finest illuminated Bibles to have emerged from Bologna in northern Italy. J. Paul Getty Museum.

Then, representatives of the National Council of Churches — copyright holder to the NRSV — reviewed the proposed changes and either accepted, rejected or offered feedback on the changes made in the updated edition. This step also included teams of reviewers from a broad spectrum of backgrounds and denominations.

Thus, overall, a huge number of scholars were involved in the project, although most worked in bite-sized areas. Upline editors sought to bring unity to the suggested edits.

In addition to incorporating updates prompted by the Dead Sea Scrolls, the project sought to strengthen the footnotes accompanying the biblical text to indicate where variant readings might be possible and to maintain the original vision of the NRSV’s style and rendering.

‘As literal as possible and as free as necessary’

A publisher’s note explains that the translation philosophy of the NRSV is to be “‘as literal as possible” in adhering to the ancient texts and only “as free as necessary” to make the meaning clear in graceful, understandable English.

The publisher further explains: “The NRSV Updated Edition sets out to be the most literal translation of the Bible available to date with its clear use of unambiguous and unbiased language. The new version gives English Bible readers access to the most meticulously researched, rigorously reviewed, and faithfully accurate translation on the market. It is also the most ecumenical Bible with acceptance by Christian churches of Protestant, Anglican, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, African American, and Evangelical traditions.”

“Translation is an art and skill. It’s a type of dance between the ancient text and modern culture,” according to David May, Landreneau Guillory Chair of Biblical Studies and professor of New Testament at Central Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City.

David May

“The NRSVue works at being accurate, which is a slippery term. From a textual perspective, the NRSVue utilizes the latest findings and assessments of textual issues. This is related to evaluating various manuscripts and certain verses, words, and phrases. Accuracy is also found in the application of insights from the historical, social and cultural arenas related to how words and phrases are used.”

As an example, he cited Matthew 2:1 where the 1989 NRSV describes the individuals seeking Jesus as “wise men.”

“It seems that this description owes more to KJV tradition and the hymnic tradition,” May explained. “So, the NRSVue uses ‘magi,’ which is really a transliteration of the original Greek word, μάγοι. The footnote lets the reader know that these magi were astrologers. A point of criticism might be that it would have been better to include ‘astrologers’ in the text and ‘magi’ in the footnote. I have for years translated magi as ‘stargazers’ to try and capture more of their identity. However, perhaps the translation committee feared putting astrologers into the biblical text because of criticism from some readers who might have an anachronistic understanding of astrologers.”

Why does this matter?

“The text-critical and philological revisions that make up the majority of the substantive revisions in this updated edition are the most basic kinds of advances in biblical research behind most important new translations and revisions over the years,” said Dalen Jackson, academic dean and professor of biblical studies at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky.

Dalen Jackson

“Scholars have continued the work of piecing together the most reliable versions of the earliest texts of the Bible and of determining which words in our contemporary English usage represent the best translation of the ancient biblical languages. It’s valuable for us to see the fruit of that work in the Bible versions we read in church and in our personal devotions and study. This updated edition of the NRSV gives us a Bible that is closer than ever to the earliest versions of the texts, and that is certainly a good thing.”

The modern influence of the Dead Sea Scrolls comes not merely from their discovery but also from advances in reading them and comparing them to other manuscripts.

“Scholars can explore relationships between ancient texts today by the use of statistical methods and computer software unimagined by previous generations,” Jackson explained.

What is ‘philology’?

“Philology” — the study of the historical development of words — requires continual examination of both the original biblical languages and of English, Jackson said. “Bible translators continue to make incremental improvements in our knowledge of what ancient Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek words meant, so it is important to incorporate that knowledge into our translations periodically.

“Also, the English language obviously continues to change, so it’s helpful for us to review translations from time to time to see that the words still convey appropriate meanings, as well as to evaluate them in light of current notions of writing style and sensitivities about language.”

One example from the NRSV update is the way persons with certain physical conditions or characteristics are named, May added.

A copy of the Gutenberg Bible in the collection of the New York Public Library.

“In one of my classes, we have an assignment to look at the various translations related to those who are presented with disabilities in the biblical text. I also have students read Kerry Wynn’s article ‘Disability in the Bible Tradition.’ One of the principles Wynn articulates is that people are not their disability but have disabilities. So, you are not a demoniac but a person possessed by an unclean spirit; you are not a blind man, but a man who is unable to see.”

Similar changes are made in the NRSV update. The original NRSV translate Matthew 9:32 as “After they had gone away, a demoniac who was mute was brought to him.” The updated version renders it: “After they had gone away, a demon-possessed man who was mute was brought to him.” Likewise, Mark 5:15 now describes a “man possessed by demons” rather than a “demoniac.”

“No doubt some will suggest that those revising the NRSVue are attempting to be politically correct; I chose to believe they are attempting to be sensitive both biblically and humanly,” May said.

Updates to gender references

The original NRSV already was ahead of most other English translations of the Bible on gender-inclusive language, but still with limits.

Take, for example, 1 Corinthians 15:1, which in the King James Version is rendered: “Moreover, brethren, I declare unto you the gospel which I preached unto you, which also ye have received, and wherein ye stand.”

In the current NRSV, the word “brethren,” which is adelphos in Greek, is rendered as “brothers and sisters,” a pattern kept in the updated NRSV. While adelphos may mean “brother” and is a masculine noun, it also implies community and, in this case, religious community. Modern translators recognize that the religious community includes both men and women.

“Chelsea Workhouse: A Bible Reading (Our Poor),” James Charles (1851–1906). Warrington Museum & Art Gallery.

The reasoning is that, as in so much ancient and even modern literature, writers begin with a presupposition that male pronouns should be used to represent inclusive ideas, as the default pronoun. But that doesn’t mean the words are addressed only to men.

Previous battles have been fought over such gender-inclusive adaptations in English translations of the Bible, most notably when a gender-neutral edition of the NIV was proposed in 1987 but didn’t happen until 2011. Today’s version of the NIV follows the NRSV in using “brothers and sisters” in 1 Corinthians 15:1 — as do many other English translation, including the New American Standard.

One holdout on retaining male language even in such cases as this, however, is the Holman Christian Standard Bible, a project and product of the Southern Baptist Convention’s publishing arm, Lifeway Christian Resources.

What the current and the updated versions of the NRSV do not do, however, is adopt gender-neutral language for the first person of the Trinity, typically referred to as God the Father. Many moderate and progressive pastors — and the editorial policy of BNG — seek to deemphasize the repeated use of “he” and “him” as pronouns for God in a general sense.

Both the current and updated NRSV continue to reference “God the Father” as “he.” Continuing with an example from 1 Corinthians, the KIV translates chapter one verse nine: “God is faithful, by whom ye were called unto the fellowship of his Son Jesus Christ our Lord.” Here, “his” is a reference to God.

Both the current and updated NRSV continue to reference “God the Father” as “he.”

The current NRSV continues this pattern in saying, “God is faithful; by him you were called into the fellowship of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord.” But the updated NRSV mutes the additional male pronoun just a bit by translating: “God is faithful, by whom you were called into the partnership of his Son, Jesus Christ.”

Another example is found in Matthew 5.45, which the KJV translates: “That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust.”

The current NRSV follows suit: “So that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.” The updated NRSV makes no changes here.

Homosexuality

Of course, anytime an English translation of the Bible is undertaken, attention quickly turns to some of the most contested passages. And in American Christianity, that often means passages related to sexuality.

The antecedent to today’s NRSV translation is the Revised Standard Version, which first introduced the word “homosexual” into the New Testament text. Researchers Ed Oxford and Kathy Baldock have documented the history of how this translation was made and how the RSV translation team later agreed they had made an error.

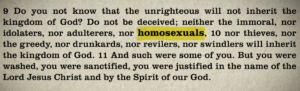

The first appearance of the word “homosexual” in an English translation of the Bible was placed in 1 Corinthians 6:9 by translators of the Revised Standard Version.

Specifically at issue is the translation of two words in 1 Corinthians 6:9 in one of the New Testament epistles’ so-called “vice lists,” a common teaching technique of the Greek world. The RSV for the first time ever translated the Greek words malakoi and arsenokoitai as meaning “homosexual.” Both Greek words are highly contested in their meaning, but the RSV became authoritative far beyond what its translators might have anticipated.

In the span of time between when the RSV was published in 1946 and when revisions were allowed to be made, several other influential English translations were produced, including the New American Standard Bible, The Living Bible and New International Version Bible.

The NIV has been especially popular among evangelical Christians. As of 2020, the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association reported the NIV as the top-selling Bible, a role it has held for many years. The NIV has been praised for striking a balance between formality and functionality, meaning staying true to the original text while presenting that text in lay-friendly English. That same attribute, though, also leads to criticism of the NIV as sometimes being less precise than biblical scholars would like.

So while the NIV may be most popular with the average person in the pew and with conservative evangelicals, the NRSV remains the most-often cited English translation among biblical scholars and mainline and progressive pastors.

The updated NRSV makes slight changes to 1 Corinthians 6:9.

Regarding 1 Corinthians 6:9, later versions of the NRSV adopted the English words “male prostitutes” and “sodomites” as translations of the two contested Greek words. Even those word choices have remained controversial, especially the use of the word “Sodomite,” which links all same-sex relations to the story of the destruction of Sodom in Genesis 19. Many modern biblical scholars — especially among moderates and progressives — believe the sin of Sodom was not homosexuality but abusive violation of ancient norms of hospitality.

The updated NRSV makes slight changes to 1 Corinthians 6:9 — “Do you not know that wrongdoers will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived! The sexually immoral, idolators, adulterers, male prostitutes, men who engage in illicit sex, thieves, the greedy, drunkards, revilers, swindler — none of these will inherit the kingdom of God.”

That adjustment is likely to further push away conservative evangelicals from the NRSV while not fully satisfying more progressive Christians who believe “men who engage in illicit sex” is still not specific enough. They argue that a better translation would speak of men who are abusive in sexual relations, such as through pederasty, the abuse of boys by older men.

In sum, the updated translation makes progress

Where would scholars and church members alike be if they couldn’t contest various interpretations of the Bible? No updated English translation is likely to solve those debates.

“I think that biblical scholars as a whole will overwhelmingly welcome this revision of the NRSV,” Jackson said. “While they may not agree with every individual decision made by the editors, the revision takes seriously the work of biblical scholarship. At its best, that scholarship seeks to learn the truth about the biblical texts by doing good detective work that identifies the best evidence for the early texts and utilizes all the best available tools in translating them.”

An illuminated Bible page from the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

May added: “For many of us, the updated NRSV, NRSVue is exciting news. One reason is that the NRSV is the basic translation we utilize in the seminary teaching context. When I began seminary in 1981 as a student, I studied, interpreted and worked from the RSV, which was good but dated, since it was done in 1952. As I began my teaching career, the NRSV came out (1989); it was better but not quite there. Now nearing the end of my teaching career, the NRSVue represents an even better updated version.”

While Bible translations often have long shelf lives, May noted, there is a need ever 30 years or so to revisit scholarship and language — “because change happens. The English language changes with a new generation, and biblical information and insights change with new explorations, discoveries, and understandings.”

Such updates continue a tradition that goes all the way back to the King James Version, the Revised Version of 1885, the American Standard Version of 1901, and the Revised Standard Version and New Revised Standard Version, Jackson said.

“The English Standard Version and the New American Standard Bible are similarly derived from revisions that go back to the KJV, but with decidedly more conservative evangelical points of view than the NRSV tradition,” Jackson continued. “Those translations, along with translation traditions such as the New International Version and Christian Standard Bible created from scratch by conservative committees, will likely continue to be the favorite Bibles of conservative evangelical Christians.

“The NRSVue incorporates the work of scholars who more broadly represent a mainline vision of Christian theology.”

“The NRSVue incorporates the work of scholars who more broadly represent a mainline vision of Christian theology, including many scholars from various mainline Protestant ecclesial traditions as well as Catholic and Jewish scholars. For more progressive Christians, the NRSVue will continue the tradition of the RSV and NRSV as a favored version, along with the Common English Bible, a fairly recent fresh translation that follows a somewhat freer translation philosophy and incorporates an even more diverse team of editors and translators.”

And Baptists have played a big role beginning in the 20th century in advancing more up-to-date language to the biblical text, May added. “One of the first was Richard Weymouth (1822-1902) and his New Testament in Modern Speech (1903). In his Preface, he indicates his goal was to consider ‘how we can with some approach to probability suppose that the inspired writer himself would have expressed his thoughts, had he been writing in our age and country.’”

Many Baptist translators have had this same goal, he said, citing as examples Edgar J. Goodspeed’s An American Translation (1923); Helen Barrett Montgomery’s Centenary Translation (1924); Robert Bratcher’s Good News for Modern Man (1966); Clarence Jordan’s The Cotton Patch Version (late 1960s-70); Barclay Newman’s Contemporary English Version (1995) and Scripture Stark Naked (2012).

One thing still lacking

“Reading the Scriptures,” 1874, Thomas Waterman Wood. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Despite the advances of the updated NRSV, one important thing appears to be still lacking, Jackson noted. While the update “highlights the ecumenical and interfaith diversity of its team, and a certain amount of gender diversity is evident as well, I am disappointed in the very limited amount of racial diversity of the editors. It doesn’t appear that any of the 34 or so editors of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and Apocrypha/Deuterocanon sections are African American, and only three of 22 New Testament editors are African American.

“White Christians, and white scholars, have to do better than this, especially considering the long history of white supremacy in our nation and its influence which extends through all previous American Bible revisions and translations.”

Related articles:

New NIV translation due out in 2011

For Godself’s sake, stop picking on the small church where Beth Allison Barr’s husband serves as pastor | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr

My quest to find the word ‘homosexual’ in the Bible | Opinion by Ed Oxford

I knew the truth about women in the Bible, and I stayed silent | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr

About disfellowshipping churches based on the ‘clear’ teaching of Scripture | Opinion by Dalen Jackson