Peace is gradually returning to Ethiopia after days of violence, tension and rioting resulted in the destruction of religious centers in some parts of the East African country.

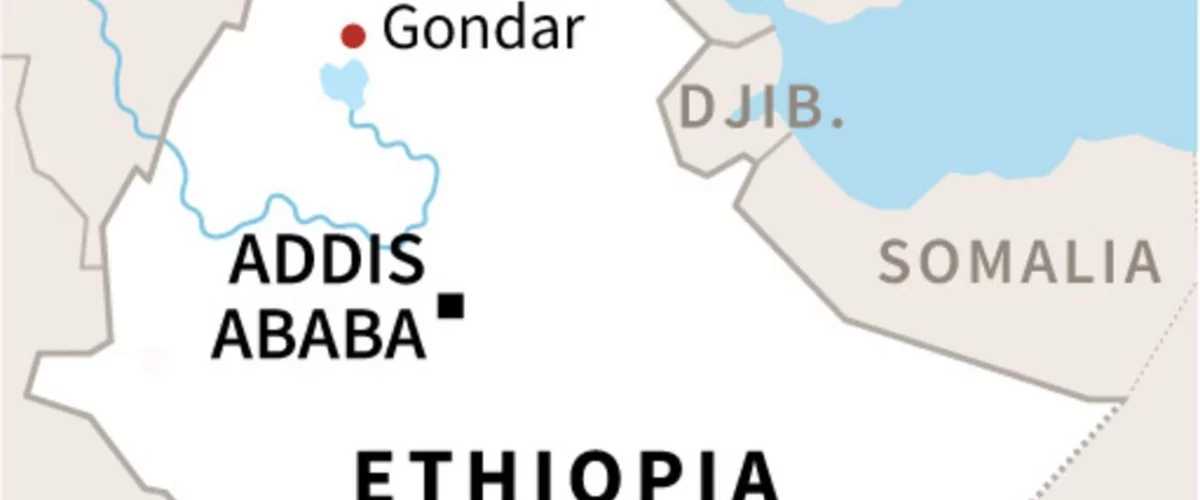

In the northern region of Gondar, 21 people reportedly were killed during a funeral procession blamed on Christian extremists by Muslims. Then in Addis Ababa, the country’s capital city, some Muslims aggrieved by the killings in Gondar rioted during the Eid al-Fitr.

And in still other places where evidence of the violence remain, residents report relief that the crises didn’t snowball into something worse. An escalation of the violence could have worsened the country’s challenges as security forces had, over a year now, been battling separatist fighters in the Tigray region of the country.

Asnake Kefale, an assistant professor of political science at Addis Ababa University, told BNG on May 5 that peace has returned to the cities: “I live in Addis. Addis is very calm. Our relationship (between people of different religious groups) whether at work or social life (hasn’t changed that much). Even Gondar, I have colleagues (there). Calm has returned to Gondar.”

Thousands of Muslims in Addis Ababa rallied demanding justice for victim’s of the attack in Gondar. (Photo: Addis Standard, Ustaz Bediru Hussien)

While noting that churches and mosques were destroyed during the mayhem, he believes “religious tolerance is still in a good position” in the country.

However, Kefale decried the violence and called on Ethiopians, including religious leaders and government officials, to learn from the experience and avoid a repeat of such. What happened in the country, particularly in Gondar, he said, came as a shock to him.

To get to know exactly what happened and avoid a repeat of it, Kefale advised the Ethiopian government to thoroughly investigate the incident and prosecute those found liable.

“We expect the government to come out and tell us the facts of what really happened. There are a number of theories, different kinds of theories about what really happened,” he said. “There are forces, of course (who thrive in crisis, conflict). There is also the political interest. For some, religion could be an instrument to mobilize people for their own political advantages. The government should carry out its obligation, its responsibility. Those who committed crimes from both sides need to be brought to justice, they should be held accountable. I think that would bring solution to the crisis.”

Michele Bachelet, United Nations high commissioner for human rights, also thinks a comprehensive inquest would help chart a new chapter for the country. In a news release dated May 7, Bachelet urged Ethiopian authorities to ensure that justice is done on the matter.

Michelle Bachelet

“I call on the Ethiopian authorities to promptly initiate and conduct thorough, independent and transparent investigations into each of these deadly incidents and ensure that those found to be responsible are held to account,” she said. “Individual accountability of perpetrators is essential to prevent further violence. Those arrested must be fully accorded their due process and fair trial rights in accordance with international human rights law, without discrimination.

“To prevent further inter-religious violence, it is crucial that the underlying causes of this shocking violence are promptly addressed, with the meaningful participation of survivors, families and affected communities.”

Counting the cost of the conflict, the U.N. commissioner said: “I understand two mosques were burned and another two partially destroyed in Gondar. In the apparent retaliatory attacks that followed, two Orthodox Christian men were reportedly burned to death, another man hacked to death, and five churches burned down … . There was further violence on April 28 in Debark town in the Amhara region, and Dire Dawa city in the northeastern Afar region.”

In the end, “police have reportedly arrested and detained at least 578 people in at least four cities in connection with the violent clashes.”

There are some who believe the tense atmosphere in Ethiopia caused by the Tigray war may have contributed to the religious disturbances.

Emamsy Mbossa Ngossoh

Emamsy Mbossa, a graduate of negotiation and conflict resolution from Columbia University, is one such person. Unlike Kefale, Mbossa said he wasn’t surprised at what happened in Ethiopia as a precedent had been set before now.

“It wasn’t a surprise for me to see the outbreak of violence even if this one is a faith-based type of conflict,” he explained. “In fact, with the ongoing climate of violence in the country for several months (caused by the Tigray war), there’s a social unrest and fragility. Multiple social disparities can trigger disputes at any time, especially in this moment where not all the basic needs of the population are met.

“This scenario is not new to the Ethiopians, and it can only revive the preexisting tensions. Back in 2019, five people suspected of burning down four mosques in the town of Motta, located in the same region, were arrested by the Ethiopian authorities. Now it’s an alarming situation that needs to be taken care of immediately before it gets out of control.”

While also calling for a thorough and transparent investigation into the incidents to ensure that culprits are brought to justice without discrimination,” Mbossa said, “the current Christian and Muslim clashes represent a major threat to stability in the short and long term in Ethiopia,” and that “with religion being a latent source of conflict in this region, even a minor event can cause the conflict to escalate at any time, (thereby) generating interfaith fear and hostility for a longer period.”

“With religion being a latent source of conflict in this region, even a minor event can cause the conflict to escalate at any time.”

Ethiopian security agencies already are working to prosecute the culprits. After the incidents, the country’s Peace and Security Joint Task Force disclosed that it had arrested suspects and believes the violence was instigated by “historical enemies.”

However, some witnesses at Meskel Square, a public center in Addis Ababa close to the International Stadium axis where chaos erupted during the Eid al-Fitr, blamed security officials for contributing to the chaos.

Ustaz Abubeker Ahmed, an Ethiopian preacher, said he was informed by a security official that a police officer accidentally discharged teargas during the Muslim festival.

Prior to the violent incidents, Ethiopia, a multiethnic and religious country of about 115 million people, was not, despite the incident cited by Mbossa in 2019, a country usually associated with religious violence. The country is about 30% Muslim and 70% Christian.

“Nothing good will come out of religious violence,” Kefale predicted. “As a country we have a very good record of tolerance between Christians and Muslims. We need to maintain that tradition. The government and leadership of different religions need to do what they should do: they should teach their followers that interfaith violence wouldn’t bring anything good. Religious families should begin to teach tolerance and support each other because we have some other problems like inflation. There are conflicts here and there, there are challenges, but I think people in general like to maintain the unity of the country in spite of differences. The differences could be about the direction, the policies or structure of the country but I’m not really that worried about the unity of the country.”

“Nothing good will come out of religious violence,” Kefale predicted. “As a country we have a very good record of tolerance between Christians and Muslims. We need to maintain that tradition. The government and leadership of different religions need to do what they should do: they should teach their followers that interfaith violence wouldn’t bring anything good. Religious families should begin to teach tolerance and support each other because we have some other problems like inflation. There are conflicts here and there, there are challenges, but I think people in general like to maintain the unity of the country in spite of differences. The differences could be about the direction, the policies or structure of the country but I’m not really that worried about the unity of the country.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian born-freelance journalist who currently lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.

Related articles:

In Tigray, Ethiopia, six months of pain, suffering and disaster