In the year 1612, British Baptist/dissenter Thomas Helwys published A Short Declaration of the Mystery of Iniquity, the first English call for universal religious freedom. Addressed to King James I, it began: “Hear, O King, and despise not the counsel of the poor, and let their complaints come before thee. The king is a mortal man and not God: therefore hath no power over the immortal souls of his subjects, to make laws and ordinances for them, and to set spiritual Lords over them.” Such antiestablishment protest led to Helwys’ incarceration in New Gate Prison, where he died around 1616.

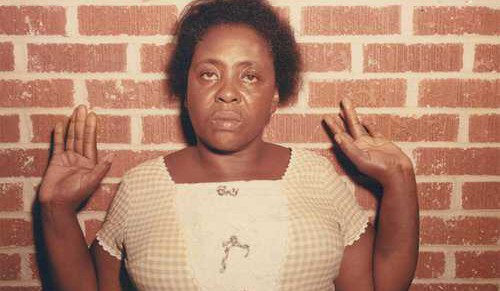

In June 1963, returning from a Southern Christian Leadership Conference voter registration program in South Carolina, a busload of African Americans stopped in Winona, Miss., requesting service at a whites-only lunch counter. Forced to vacate the premises by local police, a SCLC representative began recording license plates of their police cars. That action produced the group’s arrest, among them civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer.

Bill Leonard

Beatings followed incarceration. When police discovered the presence of the “infamous troublemaker” Hamer, her ordeal became even more intense, carried out by two African American inmates compelled by police, who warned them, “If you don’t beat her, you know what we’ll do to you.” The details of that abuse are even more heinous than described here, as documented in Charles Marsh’s God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. Marsh writes, “The experience in the Winona jail proved to be a kind of Golgotha for Mrs. Hamer, an experience of intense physical pain and humiliation.” She would not be deterred.

In August 2017, 32-year-old Heather Heyer was killed in Charlottesville, Va., run down by a 20-year-old white supremacist as she peacefully counter-protested a “Unite the Right” KKK, neo-Nazi protest. The driver, James Alex Fields Jr., received two life sentences for his actions. Nineteen other people were injured as a result of his crime.

Those accounts from three different centuries reflect the necessity and peril of protest for justice and conscience sake, as well as the vulnerability of protesters, actions that repeatedly send me back to Edwin S. Gaustad’s Dissent in American Religion (1973), a classic perhaps more relevant, no, essential, now than at publication a half-century ago. I’ve cited Gaustad’s remarkable insights frequently in this space, but apparently not enough.

“Those accounts from three different centuries reflect the necessity and peril of protest for justice and conscience sake.”

Gaustad writes that “the religious dissenter cries out against absurd confinements in manners and morals, against the fatuous kowtowing of body or of mind, against the circumscribing of vision or of aspiration, against evil that (humans) do in the name of good, against indifference, insensitivity, and inertia.”

He warns: “Society’s and religion’s problem is that amid the clanging cymbals of consensus it is frequently difficult to hear what the dissenter is trying to say. One has to make a special effort to listen. He that has ears to hear, said a dissenter of ancient days, let him hear.”

An April 24 New York Times article titled “G.O.P. Bills Target Protesters (and Absolves Those Who Drive Into Them)” notes that in 2021 one of society’s increasing problems involves the dramatic increase in legislation that would criminalize peaceful dissenters while threatening the right to dissent itself, much apparently aimed at Black Lives Matter protests.

Indiana Republicans propose a bill that forbids those convicted of “unlawful assembly” from state employment, even elective office. A proposed Minnesota law would restrict those convicted of “unlawful protesting” from securing student loans, unemployment funds or housing aid. Oklahoma’s governor recently signed a law relieving drivers of liability should their auto strike, even kill a person should the driver be “fleeing from a riot … under a reasonable belief that fleeing was necessary to protect the motor vehicle operator from serious injury or death.” Iowa legislators passed a similar law this month. Could Heather Heyer’s killer have benefited from such a law?

Turns out Republican legislators in 34 states have proposed 81 “anti-protest bills” so far this year, more than twice the number from 2020. The Times article suggests that what is labeled as “anti-riot” legislation, conflates “the right to peaceful protest with the rioting and looting that sometimes resulted from such protests.” Laws against rioting, looting and public endangerment already exist throughout state governments, leading civil libertarians to fear that new legislation may undermine lawful freedom of speech and assembly.

“Laws against rioting, looting and public endangerment already exist throughout state governments.”

Riots have occurred alongside recent protests in Portland; Minneapolis; Kenosha, Wisc.; and oh yes, Washington, D.C., Jan. 6, 2021, all unacceptable. Yet in an October 26, 2020, Washington Post article, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman studied that summer’s public protests, most related to Black Lives Matter issues, and discovered that only 3.7% brought about vandalism or property destruction. Many involved vandalisms, not from police or protesters, but actions carried out by others. Their data indicated that some 96.3% of protests showed no damage to property or injury to police, with no injuries involved in 97.7% of the “7,305 events in thousands of towns and cities in all 50 states and D.C., involving millions of attendees.”

Chenoweth and Pressman conclude: “These figures should correct the narrative that the protests were overtaken by rioting and vandalism or violence. Such claims are false. Incidents in which there was protester violence or property destruction should be regarded as exceptional — and not representative of the uprising as a whole.”

Thus we ask: Is legislation that appears to link protest with violence necessary for our protection or is it yet another socio-political vehicle for “illegalizing” protest and dissent itself?

That question, read through Ed Gaustad’s text on religious dissent, prompts the following:

- Throughout Christian history, one person’s protest is often another’s orthodoxy. Today’s dissenters support or oppose a wide spectrum of opinions on a vast array of issues, including politics, slavery, race, war, pacifism, abortion, homosexuality, church/state, religious freedom, gender, and economics, to name only a few. Gaustad: “The American experiment, the American folly, was to place both orthodoxy and dissent upon the same shifting platforms of public favor and public support.” Inevitably, conscience produces dissent and holds it accountable.

- Dissent and protest can divide, well, everything — nations, cultures, families, churches, world without end. Gaustad: “Dissent is not a social disease … its reception is different in the marketplace or on the march, in the town meeting or within the church council, at the political forum or even around the family hearth.” It’s about community. Dissent unites and fragments communities for conscience sake.

- In 2021, must legislation that undermines peaceful protest by connecting it with violent rioting be challenged, even protested? Gaustad: “Its answer determines how firm or fine that line between a society that is open and one that is closed, a society that is virile and creative as opposed to one that is sterile and decadent. To steal a rhythm from Reinhold Niebuhr, consent makes democracy possible; dissent makes democracy meaningful.” Legislation should too.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.