Imagine if America’s coalition of conspiracy theorist, cowboy Christianity had colonized its way into the world of international politics and sexual abuse cover-ups under the guise of spreading the gospel. Research scholar Mary Li Ma believes this isn’t an imaginary scenario, but a very real one today.

Li Ma, who is the author of nine books, specializes in social theory and the intersection of China studies, religion, gender, the art market and globalization. She is an advocate for women’s rights and for understanding urban poverty.

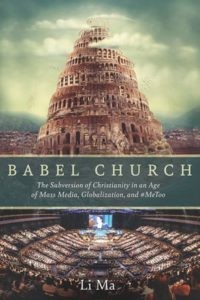

Her latest book, Babel Church: The Subversion of Christianity in an Age of Mass Media, Globalization, and #MeToo, discusses how American conservative evangelicalism has exported its gender-driven power dynamics and obsession with Donald Trump to China.

Her latest book, Babel Church: The Subversion of Christianity in an Age of Mass Media, Globalization, and #MeToo, discusses how American conservative evangelicalism has exported its gender-driven power dynamics and obsession with Donald Trump to China.

She recently gave an exclusive interview to Baptist News Global about these issues.

The American evangelical culture of the 1990s was a converging of purity culture, Left Behind culture and capitalism that fueled a strong fear among conservative evangelicals of their neighbors on the left, a toxically masculine embrace of hierarchy in the home, and an unparalleled support of political violence and war in the pursuit of retributive justice. How was the culture of Christianity in China developing in the 1990s? Was there a similar conspiratorial culture growing in China as well? And how did it compare or contrast to the culture of conservative evangelicalism in America?

In China, the 1990s saw the re-entry of American mission workers. Some went there on tourist visas; others were dispatched by organizations such as Campus Crusade. By then, the general public’s knowledge about Christianity in China had been diminished after a few decades of missionary absence.

Because of a more liberal political climate, people were more open to the basic message of the gospel, which was perceived as part of Western culture. At the same time, there was caution against other cultural imports from the West that threatened the traditional family values. So it was easy for American evangelicalism’s conservative camp to find disciples in China. Even some Chinese academics who were not Christian believers reckoned that America had social problems that conservatism may serve as a remedy. So they thought such conservative remedies may also work in China.

About gender roles, it was not until a decade later in the 2000s when a patriarchal belief was gradually institutionalized, partly through the translation of some conservative preachers’ books and the implantation of some brands of ministry. But even in the 1990s, South Korean missionaries and some traditional sects of Chinese Christianity also perpetuated the understanding of conservative gender roles in Christian families.

About gender roles, it was not until a decade later in the 2000s when a patriarchal belief was gradually institutionalized, partly through the translation of some conservative preachers’ books and the implantation of some brands of ministry. But even in the 1990s, South Korean missionaries and some traditional sects of Chinese Christianity also perpetuated the understanding of conservative gender roles in Christian families.

One of the dominant emotions I remember feeling within American evangelicalism in the 1990s through the 2000s was a fear of persecution against Christians. We often were warned that if the Democrats didn’t usher in the Tribulation, then they would at least bring persecution against American evangelicals like was reportedly happening to Christians in China. What was the experience of persecution against Christians in China like during this time? And how were Chinese Christians becoming attracted to American evangelicalism?

The 1990s was a honeymoon phase for the U.S.-China relationship as the latter re-emerged from previous political turmoil and continued to liberalize the economy. So many Chinese liked to learn English and befriend Americans. Some found Christianity appealing also because they admired American culture.

As a result, the 1990s was actually a decade of exponential growth for the Christian population in China. The state legalized the publishing and selling of Bibles a few years earlier (1987). The entire society was seeing a new open window to the outside world. So “marginalization” is a more accurate term than “persecution.”

Christians in China were marginalized in the sense that they were expected to keep the faith to themselves. Unlike a few decades ago, they now had the freedom to choose and practice a religious belief in private. Evangelism within close-knit groups was frequent and effective. State churches became overcrowded. House churches quickly multiplied.

By the late 1990s, Chinese believers who befriended American missionaries in China were a fresh new generation of converts. There was a leadership gap. So these new converts, some accepted through praying a simple prayer, relied on missionaries as mentors.

Books by Chinese authors about the Puritan Pilgrims on the Mayflower and how America was founded as a “Christian nation” were written and widely circulated.

This means that they were more susceptible to their influence, which was always a kind of short-term imprinting instead of long-term walking-alongside mentorship. Many looked up to mission workers from America because the latter represented a more advanced culture or even a “Christian civilization.”

Books by Chinese authors about the Puritan Pilgrims on the Mayflower and how America was founded as a “Christian nation” were written and widely circulated. So it was a trend like in the 1920s, with a more liberal atmosphere toward Western culture; but the danger of deculturalization for the indigenous community also was there.

In the mid 2000s, Together for the Gospel and The Gospel Coalition began organizing major conferences in America, which led to a popularizing of Calvinism and complementarianism through men such as John Piper, Tim Keller, C.J. Mahaney and John MacArthur. While appealing to the gospel and to the story of Adam and Eve, these men promoted a complete male authority over marriage, the family and church. How did this vision for male control resonate with Christian men in China? And how did the spread of complementarianism in China begin to affect the Chinese women in their families and churches?

It was about this time when a complementarian theology, with these Reformed brands from America as you mentioned, were imported to China. The first theological exchange was not always about gender roles. These Reformed brands tend to deliver a seemingly more intellectually sophisticated system of theologies to believers who found the “easy-believeism” kind of Christianity too shallow and compartmentalized.

Translated sermons and books by conservative Reformed pastors seem to represent the kind of “Protestant orthodoxy” especially with emphasis on the significance of John Calvin and the Reformation. Then gradually topics like “the order of creation” and “male headship” in church and family relationships were also being discussed and even trended as signs of a revival toward orthodoxy.

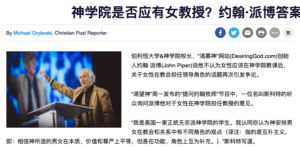

John MacArthur on a Chinese website

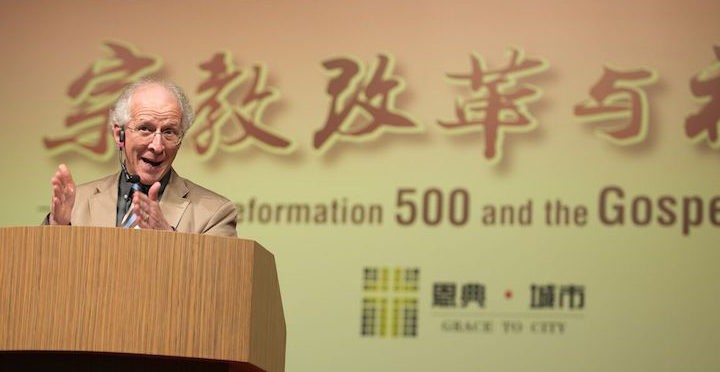

The popularity of these themes among urban young professionals had to do with challenges in marriage and family life. So there was a demand for relevant pastoral care, but the market at the time presented voices from these preachers such as John Piper and Timothy Keller. TGC’s promotions of Keller’s translated books are highly successful, so that became a top brand. The height of all this frenzy was around 2017, the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. Timothy Keller himself spoke at a Hong Kong conference addressing young Chinese pastors.

Many of China’s churches were founded by women, but when this conservative Reformed theology entered and spread, there was a trend to not only exclude women from leadership, but teaching spiritual submission of women to men in all areas of life. This inevitably created lots of tragedies from women preachers being deposed and publicly humiliated, pregnant female staff being fired, to single women and single mothers being sexually preyed upon by abusive male leaders in the church.

As Chinese Christian men began following the lead of American evangelical men in taking control of their marriages, families and churches, how did they envision extending their influence within the world of Chinese politics? What media or technological resources did they have at their disposal to pursue their political agenda?

My 2019 book documents how a church community in China not only reformed its structure in terms of gender roles but also heavily relied on a Republican, anti-communist and Christian civilization-themed vision of government. Like some evangelicals in America, they liked to hold public worship meetings in front of police stations, and when taken away for public security concerns, they claim to have been persecuted.

John Piper on a Chinese website.

From 2017 to 2018, their story got a lot of publicity in right-wing media outlets like World magazine and the Christian Post, then picked up by other mainstream media. But my book pointed out the discrepancy of these media stories and their negligence to pervasive abuse in the church. I also questioned the two main journalists over the phone, both of whom admit having observed the church leadership to be “dictatorial” but eventually chose to paint them into anti-communist heroes of the Chinese church.

After publication, the book got a lot of heat from TGC. How do I know that? If you read the reviews under this book on Amazon, the top bashing piece (using a fake name) was the same TGC posted on its Chinese website.

How did American evangelical organizations such as The Gospel Coalition and Redeemer City to City begin partnering with Chinese Christian organizations? What roles did they play in shaping the values of Chinese Christianity? And what effect did the secretive nature of ministering in China under the threat of persecution have on accountability for these partnerships?

Since 2010, The Gospel Coalition and Redeemer City to City have been training pastors from China. Through another PCA-affiliated ministry, they also expanded the network in many Chinese cities, subsidizing local pastors who follow the brand and its values.

“Because they have occupied a big share of the Christian publishing market in China, their presence was formidable,”

Because they have occupied a big share of the Christian publishing market in China, their presence was formidable, demanding other ministries to yield to their rules of the game. While doing fundraising in America, they tell the public that because they are serving churches in China, these American missionaries (including some Chinese Americans) need to have anonymity. This effectively deletes any accountability for what they do in China. When local believers question their ways, they either silence dissent or demand to be kept anonymous for misconduct.

So the myth of persecution has provided a convenient shield for missionary irresponsibility. Ironically, these same missionaries liked to make their names widely known on big conferences, but when someone asks for accountability in situations of abuse, they insisted on anonymity just because they were serving people in China.

In 2016, 81% of American evangelicals voted for Donald Trump to become the president of the United States. Given the Chinese Christian fascination with American evangelicalism, along with the Chinese Christian political aspirations for making China into the next great Christian nation, what effect did American evangelicalism’s enthusiasm for Trump have on Chinese Christianity? What hopes did Chinese Christians have for the Trump administration? And how is Trump viewed among Christians in China today?

It was around the same time when the narrative of “China as the next largest Christian nation” became circulated on American media by some evangelical scholars and religious liberty advocates. America has always had this obsession about Christianizing China (especially a communist one after 1949) since more than a century ago, so that kind of narrative was favored by many.

Despite Trump’s explicit anti-Chinese racism, evangelical leaders in China and America formed a kind of coalition.

Trump’s election in 2016 certainly heightened this Christian civilization narrative among church leaders in China who grew increasingly dissatisfied and impatient with the regime. They hoped Trump could help check some encroaching religious regulations in China. But there was a more fervent pro-Trump wave among evangelicals and pastors in China in 2020, mainly because of disinformation on Chinese social media. So despite Trump’s explicit anti-Chinese racism, evangelical leaders in China and America formed a kind of coalition — they think Trump is right in bashing China’s regime, a major obstacle to the realization of their “Chinese Christian civilization” dream.

The same Chinese evangelical leaders who propagated this “Christian civilization” narrative were the same core group that signed a pro-Republican statement in 2020 urging Chinese Americans to vote Republican.

As we’ve seen an increase in racism and violence against the Chinese community in America fueled by our own white supremacy, purity culture and obsession with retribution, what do you hope American evangelicals will become aware of regarding their power in shaping white supremacist hierarchical relationships over Chinese Christians and in exporting these race and gender power dynamics to the Chinese Christian community?

As I try to point out in my new book, American evangelicalism has been the upstream delivering theologies and practices to other parts of the world. Without fixing its own dysfunctions, these models of religious entrepreneurism already have created similarly toxic damages to indigenous faith communities.

This is not a new thing. On the one hand, we need to continue preaching against colonialism, and decolonization is a perpetual mandate. On the other hand, only America had the media resources to either enable or correct these mistakes. Not many media outlets in America are shedding light on the mess they helped create in other parts of the world.

“Not many media outlets in America are shedding light on the mess they helped create in other parts of the world.”

Who would want to hear about an anti-communist church leader in China falling from grace? The American public are either too self-involved or deep in their mess to care, or they consider it inconvenient. So far, the #MeToo and #ChurchToo movements are still correcting the corruption in America; even here, there is too much to be done. But women as a vulnerable group in other parts of the world have also suffered the same harm.

What could a healthy relationship between American Christians and Chinese Christians look like?

The same answer to the question of what a healthy relationship between white Christians and Black Christians entails. If the more privileged group reflect on that very privilege and use empathy, the relationship can be a healthy and mutually edifying one.

The whiteness of American evangelicalism and its lack of self-reflection has affected how other ethnic faith communities relate to each other. For example, most Chinese churches in America like to emulate the culture of white evangelicalism. In mainland China, although the state of Christians can be closely compared with that of Black churches in America — both have suffered from some systemic oppression and marginalization — mainland Chinese Christians tend to admire white American missionaries and celebrity leaders.

These days, it is more tragic for this kind of already challenging cross-cultural relationship to be caught up in a hyper-politicized U.S.-China international relationship dynamic. I think conscientious Christians in America should know how to reject “political lies” and demand accountability for their missionaries. They ought to be alert to ministries that over-exploit the persecution narrative while ignoring the power dynamics within a church between its leadership and congregants.

It is important to know that churches everywhere are power structures and leaders are not saints, not even in communist China. Elevating church leaders to the pedestal of sainthood always creates a façade for power abuse.