A few weeks ago, I had an epiphany. It sprang from an odd source: Episode 178 of a podcast called The Bible for Normal People, “Pete Ruins Isaiah.” Pete Enns is an Old Testament scholar determined to bridge the great gulf fixed between scholars and laypeople.

First, Pete “ruined” Isaiah by telling his listeners that Isaiah was written by at least three separate authors confronting distinct historical crises. Most of chapters 1 through 39 was composed by an eighth century prophet. The crisis was a looming Assyrian empire. A century-and-a-half later, a prophet known to scholars as “Second Isaiah” addressed the plight of an Israel languishing in Babylonian exile. A third Isaiah picked up the prophetic plot after the people had returned to their homeland.

Alan Bean

But Pete’s real shocker was his treatment of Isaiah 53: “He was wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities; upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his stipes we are healed.” This isn’t a prediction of the vicarious death of Jesus, he told his audience. The “suffering servant” portrayed in this passage is the nation of Israel itself.

About the servant songs

There are four “servant songs” in Second Isaiah, Enns pointed out, and in the other three, the “servant” clearly refers to Israel.

More precisely, Isaiah’s “servant” is the exile generation, those who watched in disbelief as the armies of Nebuchadnezzar leveled Jerusalem and ground the temple of Solomon to powder. Then, in a gradual and sporadic process that began in 597 and ended in 581 BCE, the leading families of Israel were periodically rounded up and dragged off to the rivers of Babylon. Every member of this exile generation watched loved ones die under the most wretched conditions imaginable. They lost their national identity. They lost their temple. And, by all appearances, they lost their God.

The big question was “Who are we?” The answer: “We are lost.”

Second Isaiah begged to differ. Galvanized by the rise of Cyrus the Great (circa 539 BCE), the prophet saw nothing but blue skies ahead.

Pete’s ruination of Isaiah may have gone a bit too far. Many Jewish scholars detect notes of messianic promise in Isaiah 53; they just don’t see Jesus as the fulfilment Isaiah had in mind. And, just because the prophet was thinking of the exile generation as he excitedly put pen to papyrus doesn’t mean the first Christians were wrong to apply his enigmatic language to the death and resurrection of Christ. How could they have done otherwise?

The big question was “Who are we?” The answer: “We are lost.”

But few serious scholars would challenge Enns’ conclusion: The suffering servant of Isaiah 53 is the exile generation.

I have long been aware of the scholarly consensus on this issue, but, until this week, I had never wrestled with its theological implications. When I did, I got my epiphany.

Healing and wholeness out of exile?

How was God using the horrors of exile to bring healing and wholeness to Israel? Isn’t that the whole point of the “Deuteronomic history” that stretches through the books of Samuel and Kings? Didn’t the exile generation deserve exactly what they got?

Not necessarily? When Second Isaiah cries that Israel has “received from the Lord’s hand double for all her sins,” he is implying that, like a parent exasperated by a disobedient child, Yahweh went a little overboard with the punishment. The exile generation was comprised of sinners, to be sure, but were these people uniquely sinful?

Second Isaiah didn’t think so. The folks too young to remember Nebuchadnezzar’s horror show were every bit as disobedient as their grandparents. “All we like sheep have gone astray;” the prophet laments, “we have all turned to our own way, and Yahweh has laid on him (the exile generation) the iniquity of us all.”

The exile generation suffered for the sins of Israel — past, present and future. And it is precisely because of this suffering, Second Isaiah insists, that a future of healing and wholeness lies open before us.

The epiphany

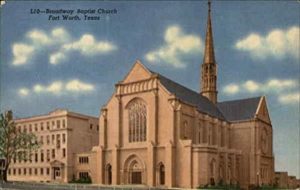

Finally, we arrive at my epiphany. My congregation, Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, has its own exile generation. For the past 40 years, the men and women of Broadway have suffered through one crisis after another. Each successive trauma has produced an exodus of gifted and dedicated members. And, counter-intuitively, God has used Broadway’s exile generation to bless people like me beyond measure.

Vintage postcard of Broadway Baptist Church

A little background. When the exile generation was young, Broadway Baptist was a flagship congregation within the Southern Baptist Convention. With thousands of members, a jam-packed sanctuary, a well-attended Training Union, vibrant Girls in Action and Royal Ambassadors programs for the youth, a world-class ministry of music, and a tight relationship with a neighboring seminary, Broadway was a religious powerhouse.

In 1952, Broadway dedicated a sanctuary modeled on Chartres Cathedral. The church boasted a powerful Casavant organ, several Christian education wings and gorgeous stained-glass windows. The congregation was highly educated and prosperous. We had a robed choir of 70 trained singers, gifted musicians and renowned ministers of music. Professors and students from Southwestern Seminary provided a bountiful source of teachers and leaders. The pews were filled with business leaders and the occasional deep-pocketed oil tycoon. In the fulness of time, the congregation added a swimming pool and a roller-skating rink to its menu of delights.

Concerns dating back to the 1980s

In 1984, James Leo Garrett wrote Living Stones, a 1,000-page congregational history to mark Broadway’s centennial. The sanctuary was still full most Sundays, but Garrett was concerned about declining participation in denominational meetings, lagging Sunday school and Training Union enrollment, and a retreat from aggressive evangelistic outreach. If the church continued to drift from the growth formula that made it great, Garrett warned, the future would be bleak.

“If the church continued to drift from the growth formula that made it great, Garrett warned, the future would be bleak.”

Garrett was a Broadway member who taught theology at Fort Worth’s Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. As he researched Living Stones, the Southern Baptist Convention was erupting into civil war. A group of Texas-based zealots was determined to gain control of the denomination. The enemy was “liberalism,” and churches like Broadway were exhibit A. Liberal congregations, conservatives charged, had turned their backs on evangelism and the inerrant word of God. The result was Ichabod: The glory had departed.

Garrett secretly feared that, without a return to its evangelical roots, Broadway eventually would be forced out of the SBC and the rich relationship between congregation and seminary would be lost.

Within Broadway’s membership, an influential minority shared Garrett’s concern. These people weren’t fundamentalists, and they loved classical music as much as anyone. But they wanted to bring back the old days, and that meant adhering to old ways.

The local scene

From the 1960s on, the inner-city neighborhood around Broadway had been deteriorating. The church responded with an ever-expanding suite of social ministries. The conservatives were uncomfortable with this trend, especially when, in the cold of winter and the heat of summer, Broadway opened its doors overnight to her unsheltered neighbors.

Shortly before Garrett completed Living Stones, Broadway ordained its first female deacons. This move exacerbated the church’s strained relationship with Texas Baptists. This made the congregation’s conservative wing nervous.

“Then Broadway’s senior pastor joined a protest sponsored by his Black Baptist counterpart. That was a bridge too far.”

In the 1990s, Broadway developed a sister-church relationship with a nearby Black Baptist congregation. Joint worship services were well-attended. Initially, Broadway’s conservative faction was comfortable with this trend. Then Broadway’s senior pastor joined a protest sponsored by his Black Baptist counterpart. That was a bridge too far. The joint services came to an abrupt end.

Little changes bothered the congregation’s conservative faction. Broadway pastors never seemed to mention Christ’s vicarious death on the Cross. They didn’t talk about the eternal consequences of unbelief.

For most Broadway members, this factional tension wasn’t particularly noticeable. Pastors and lay leaders worked hard to keep it that way. But when the discontent bubbled to the surface, a few more conservative families would disappear. As Broadway moved into the 21st century, the empty pews were impossible to ignore.

Picture this: Disaster strikes

Then disaster struck. A number of Broadway members had been working with AIDS patients since the early 1990s. For a church devoted to social ministry, the epidemic was unavoidable. But as medical treatment improved, AIDS patients began to stabilize. Drawn by a mix of gratitude and curiosity, several members of the LGBTQ community started showing up in worship.

The conservative faction was uncomfortable with this trend. But they could live with it as long as Broadway was “welcoming but not affirming.” Then several gay couples expressed a desire to appear as couples in the church’s new pictorial directory. That was the match that lit the fuse. A petition was circulated demanding the pastor’s resignation. Someone quietly offered to pay $50,000 in exchange for a quick exit. The leaders of the conservative faction had grown desperate. With each successive exodus, their ranks had thinned. If they didn’t make a stand here and now, the game was lost.

“The leaders of the conservative faction had grown desperate. With each successive exodus, their ranks had thinned. If they didn’t make a stand here and now, the game was lost.”

But their aggressive tactics horrified the congregation’s progressive leadership. Angry conversations broke out in the hallways after Sunday school. The rancor spilled into the local media.

The humiliation of Broadway’s exile generation was complete.

Now we have an exile generation

None of this compares with the plight of Isaiah’s exile generation, or to the struggles of most Black churches. Nobody torched the sanctuary. No one was lynched. We still have our jaw-dropping sanctuary. If anything, the choir is better than ever.

But make no mistake, Broadway (like many churches of like faith and practice) has its exile generation. Men and women who remember past glories. Our exile generation were children and young adults when the current sanctuary was built in the early 1950s. If congregational vitality is measured in dollars and attendance stats, Broadway is but a shadow of its former glory.

An entire generation moans in lonely exile from its past. There has been so much rejection. So many broken friendships. So much regret.

But whether this exile generation realizes it or not, they have done great things. They have sailed uncharted water, broadened their understanding of the kingdom, found the courage to live with the consequences.

In the eyes of many, perhaps in their own eyes, the exile generation was “despised and rejected by others, a people of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” Like Isaiah’s exile generation, they have grappled with the hard questions of meaning and identity: Where is God in all this. Who are we?

There was no easy path to the right answer. We worship a God who bears the sin and suffering of a broken world; as God’s people, we can do no less. We have done no less. Our pain is productive because it is rooted in faith. Kingdom living isn’t supposed to be easy.

Nancy and I have been part of the Broadway family for a little more than a decade. We are not part of Broadway’s exile generation. But we, and hundreds of people like us, are reaping the benefits of a church’s struggle.

“Out of their anguish, we see light” (Isaiah 53:11). Or, to paraphrase Psalm 126, what they have sewn in tears, we reap with shouts of joy.

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

On building, planting and faithful questions in a time of exile | Opinion by Paul Baxley

The church in exile: How will we respond to the marginalization of Christianity in American society? | Opinion by Doyle Sager

Do you wonder if you’re the only one who believes the way you do? | Opinion by Jason Koon