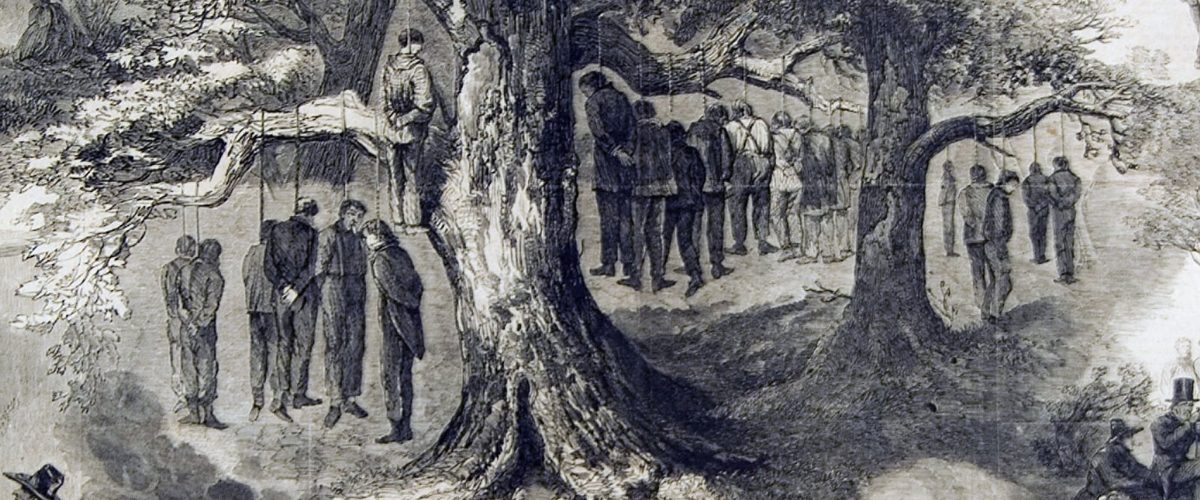

People of faith must rise up against capital punishment as a system of legalized lynching and retribution designed to suppress people of color through intimidation, torture and death, according to a recent panel of legal experts and anti-death penalty advocates.

Participants in the inaugural “Richard Wright Summit: The Father-Daughter Legacy” also urged churches, community groups and others to become more vocal opponents of the inhumane conditions endured by death row prisoners and to see through the false claims that capital punishment is less of a burden on taxpayers than long-term prison sentences and that it helps bring closure to the families of murder victims.

The discussion, sponsored by the Elaine Legacy Center, was moderated by Arkansas judge and pastor Wendell Griffen, who also is a BNG columnist.

Panelists were Little Rock attorney Furonda Brasfield, director of leadership development for the 8th Amendment Project, and Julia Wright, a veteran in the national anti-death penalty movement and daughter of the late Richard Wright, whose 1940 novel Native Son and other novels and short stories exposed the oppression of Blacks in the U.S. His book The Man Who Lived Underground was written in 1941 but published posthumously this year.

Wendell Griffen

Echoing themes he has written about for BNG, Griffen said it should be blatantly obvious that the death penalty in America is used mostly against people who are Black or brown. “It’s not justice, it’s bloodlust. Grief isn’t lessened. They (victims’ families) don’t start missing their loved ones less. That lie needs to be confronted.”

The June 17 virtual discussion occurred just days after the Pew Research Center released a new national survey showing that a majority of Americans support capital punishment.

“Six in 10 U.S. adults favor the death penalty for people convicted of murder, including 27% who strongly favor it,” Pew found. “About four in 10 (39%) oppose it, with 15% strongly opposed. Support is strongly associated with a belief that when someone commits murder, the death penalty is morally justified.”

However, close to 80% of respondents admitted to having concerns about the possibility of innocent persons being executed and most said they don’t believe capital punishment is a deterrent to homicide. Respondents also saw that race is a determinant in the use of state-sponsored executions.

“A majority of Americans (56%) say Black people are more likely than white people to be sentenced to the death penalty for being convicted of serious crimes,” the study’s authors wrote. “This view is particularly widespread among Black adults: 85% of Black adults say Black people are more likely than whites to receive the death penalty for being convicted of similar crimes.”

Other data bear out the truth of the racism behind the capital punishment.

“People of color have accounted for a disproportionate 43% of total executions since 1976 and 55% of those currently awaiting execution. A moratorium of the death penalty is necessary to address the blatant prejudice in our application of the death penalty,” according to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Julia Wright

But for Wright, family history and experience have taught her about the brutality and disparities of the death penalty. She called it “a crime against humanity, basically.”

As a child, she learned an uncle had been lynched in 1916. Her father, who was 8 at the time, asked why the family hadn’t tried to do something about it.

“His mother slapped him into silence,” she said. “The impact of that lynching on that child was so tremendous, I believe that is why he became a writer.”

But she was changed by that story, too. “Those words have reverberated as ghosts in my mind through the times, through the decades, and have sent me on my quest for justice for those who were lynched — the high tech lynchings on our death rows.”

For 40 years, her activism has been devoted to attempting to free Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Black Panther party member and journalist who in 1982 was sentenced to death in the killing of a Philadelphia police officer a year earlier. After decades on death row, his sentence was commuted to life-without-parole in 2011 and he continues to file appeals.

Abu-Jamal’s situation bears witness to the brokenness of the nation’s racist death penalty system, Wright said.

“He was the wrong color: he was Black. That was already a sentence” and “he had the audacity of becoming an award-winning journalist” who exposed police brutality, she said. “You get punished for going up the ladder like that.”

Griffen added that Abu-Jamal has maintained his innocence since his trial. “It shows all the more the illegitimacy of the death penalty, the racism of capital punishment and how capital punishment was used to penalize a Black man exposing police brutality.”

Try to recall a time when a wealthy white person was sentenced to death.

Try to recall a time when a wealthy white person was sentenced to death, he said. “In the U.S. it is used predominantly, almost exclusively, to target people who are poor and not white. That disparity is glaring beyond contradiction.”

Griffen added that the conditions for death row inmates and those serving life without the possibility of parole often cause them to suffer in solitary confinement for decades. “There is a special hell that goes with being on death row.”

Civil rights groups and churches must lend their voices in opposition to these conditions and practices, Griffen said. “We need to see it as a communal issue, an issue of social justice. It’s too big for individual families to fight alone.”

Furonda Brasfield

But convincing religious groups to participate in the movement isn’t always easy, said Brasfield, who said she learned this as the former leader of the Arkansas Coalition Against the Death Penalty.

“I tried to organize faith leaders and often ran into — with some exceptions — a brick wall trying to organize people of faith,” she reported.

The selling points for the cause, however, are numerous and powerful, Brasfield said. “We know it is morally wrong, it is not cheaper (than other forms of punishment) and it does not deter crime. Murderers don’t stop and have moments of clarity.”

She urged death penalty opponents to educate themselves about trends, including efforts in some states to use firing squads or gas to kill prisoners and the continued racial disparity among death row inmates.

“Capital punishment is racist. That is the bottom line,” Brasfield said.

“It’s legalized lynching,” Griffen added. “Let’s call it what it is.”

Related articles:

The case of Rodney Reed: A call to abolish state-sanctioned lynching known as capital punishment | Opinion by Wendell Griffen and Laurie Umansky

Final vote sounds the death knell for capital punishment in Virginia

The death penalty is dying a slow death; it’s time we pull the plug | Analysis by Stephen Reeves