David Sheldon Fearon, 84, died peacefully in his home in Nanaimo, Vancouver Island, B.C. Canada at the beginning of January.

On Oct. 22, 1959, Fearon, then a 21-year-old seminary student at McGill University’s School of Religious Studies, Montréal, Quebec, wrote a five-page letter to Luther A. Weigle, head of the translation team for the newly published Revised Standard Version of the Bible. Fearon questioned the team’s combining and translation of two Greek words in 1 Corinthians 6:10 to the single word “homosexual.” Until the New Testament of the RSV was published in 1946, the word “homosexual” never had appeared in any translation of the Bible.

Fearon was raised in Lenoxville, Quebec, the son of Earl, an iceman, and Evelyn, a primary school teacher. When Fearon was 6, his mother realized he had a strong spiritual bent. As a result, Evelyn decided to change her church affiliation to the United Church of Canada, where the religious education was stronger.

Fearon was raised in Lenoxville, Quebec, the son of Earl, an iceman, and Evelyn, a primary school teacher. When Fearon was 6, his mother realized he had a strong spiritual bent. As a result, Evelyn decided to change her church affiliation to the United Church of Canada, where the religious education was stronger.

In sixth grade, he developed his first “crush” on smart and handsome Dennis. He became nervous, shy and uncomfortable around boys, and he began to develop a stammer. At 16, he noticed a book at the town’s magazine stand, The Divided Path, subtitled “the story of a homosexual.” He thought, “Could he be like me? Maybe I’m not the only one. Maybe there are more people like me that just want to like and be liked by another boy.” Careful not to let the clerk see the book’s face, he paid and brought the book home to read.

‘Mother, I’m gay’

His mother seemed continually disappointed that her younger son did not seem to be “meeting a nice girl.” After all, Gene, Fearon’s older brother, seemed to date several girls simultaneously. To put an end to her nagging, he told her, “Mother, I’m gay.”

“David, you can’t be gay, you’re not a child molester or a pedophile.”

It was 1954, and his stunned mother responded, “David, you can’t be gay, you’re not a child molester or a pedophile.” As would become a lifelong pattern he gathered resources for his mother to read so she might understand what homosexuality meant.

Upon graduating from high school, Fearon attended Bishop’s University in Lennoxville as a day student. He studied history and English, hoping to become a teacher like his mother. While a student at Bishop’s, he served with a Royal Canadian Air Force Auxiliary Squadron from 1955 through 1959.

The system acted as an early warning detection of Russian bombers that might potentially come to the United States from the north, over Canada. Serving in the RCAF was a good opportunity for Fearon to become more comfortable being around other young men his age, something that in the past made him nervous.

Although Fearon had been solidly secure in his faith and beliefs since childhood, now that he was older and taking classes in chemistry and biology, and learning about evolution and Darwinism, he began to think more about the existence of God. He hit a crisis of faith and sought the counsel of his minister.

“I’m not sure God exists,” he confided in Leonard Outerbridge. The minister asked him to pray over the Christmas break and come to his own conclusions.

Two weeks later, Fearon was back in Outerbridge’s office. “Yes, I have found what I was looking for!” Having known David for many years, the wise minister asked, “David, do you feel called to the ministry?” In his mind, Fearon thought, “What am I getting myself into? I am a stammerer, and I’m gay.”

“God fixed my stammer, but not my homosexuality. He must be good with it.”

Outerbridge invited Fearon to give the Sunday night sermon, the service most attended by his peers, his fellow students. He stood to give the sermon, delivered it clearly and never stammered again. It seemed settled to Fearon: “God fixed my stammer, but not my homosexuality. He must be good with it.”

The United Church of Canada gave him a scholarship to attend McGill University School of Theology. The denomination had adopted the RSV as its official text for service and worship in 1952 when the full version of the translation was published.

Reading 1 Corinthians 6

The Revised Standard Version is an English translation of the Bible that was popular in the mid-20th century. It posed the first serious challenge to the King James Version, aiming to be both a readable and literally accurate modern English translation of the Bible.

Fearon had been raised reading the King James Version of the Bible. Eventually, in his divinity program, he came across 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 in the RSV: “Do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived; neither the immoral, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor homosexuals, nor thieves, nor greedy, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor robbers will inherit the kingdom of God.”

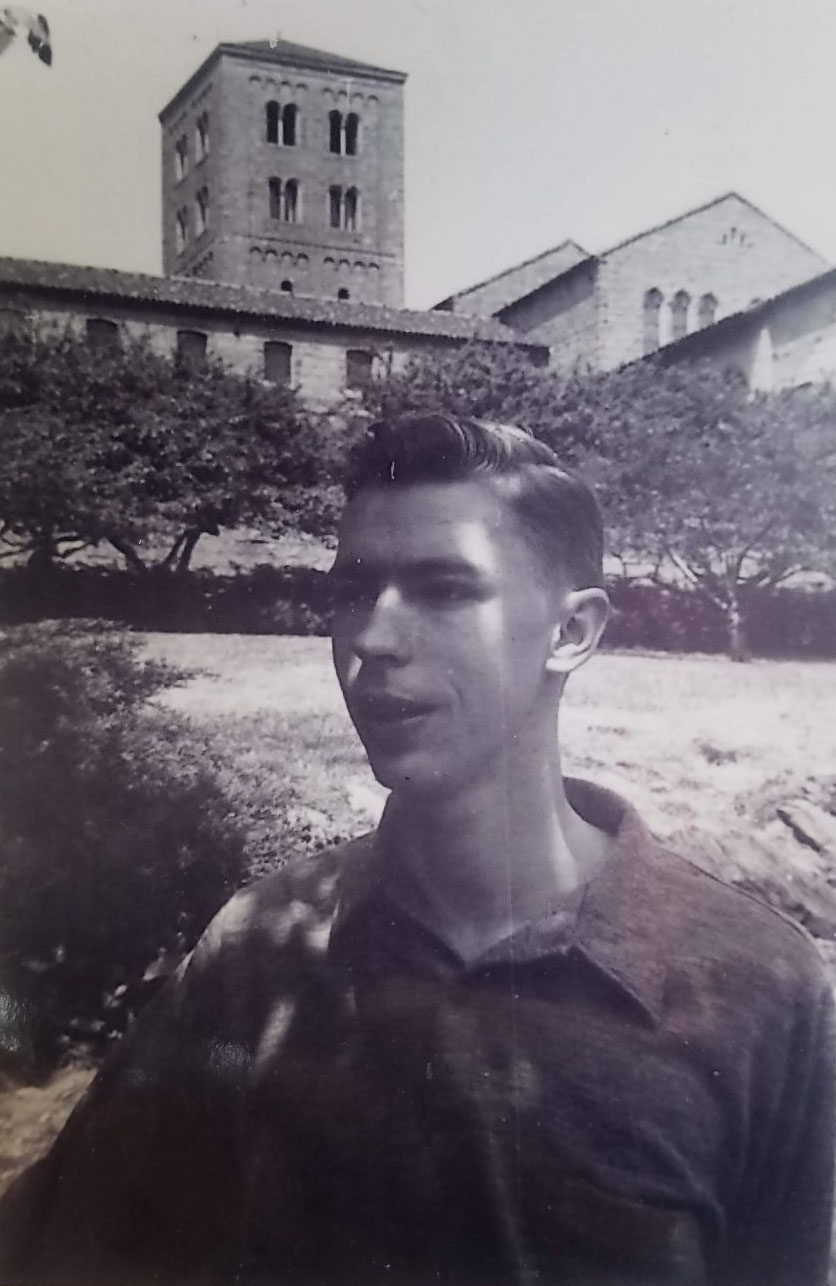

David Sheldon Fearon circa 1962 (Collection of the author)

“Well,” he puzzled, “that doesn’t make sense to me. God called me to the ministry, and he knew I was homosexual. Now I am reading that homosexuals will not enter the kingdom of God. How can that be?”

Then Fearon noticed a small notation “j” beside the word “homosexual” indicating a footnote that read: “Two Greek words are rendered by this expression.”

“This translation has to be wrong, and if so, it is a terrible disservice to homosexual people,” Fearon suspected. “It shows strong prejudice on the part of the translation team.”

The RSV translation of the passage deeply bothered him. The more he thought about it, he thought that the RSV translation of the 1 Corinthians verse would lead to the further discrimination of gay people, but this time, from the church. But Fearon knew how to dig in to find answers to his questions. He had been doing it since his teenage years.

He was a good Greek student both at Bishop’s University and now at McGill. He knew it was essential not to simply read translated words in English versions of the Bible. Instead, he was trained to return to the original Greek texts to better understand the original meanings.

Digging deeper into the text

After reading the RSV 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 footnote, he took out his Greek Bible and looked up the two words that had been combined to form the one word “homosexual.” The two Greek words are malakos and arsenokoites. In his interlinear New Testament that compared the Greek text with the literal translation immediately above it, Fearon learned that the word arsenokoites was likely to have been coined by Paul the Apostle to address a specific situation happening within the church at Corinth.

Corinth, an ancient seaport city, regularly saw sailors, and to service their sexual needs, prostitutes. In the ancient world and in Greek culture, men enjoyed both male and female prostitutes, but more often men preferred the less complicated services of men, particularly young men.

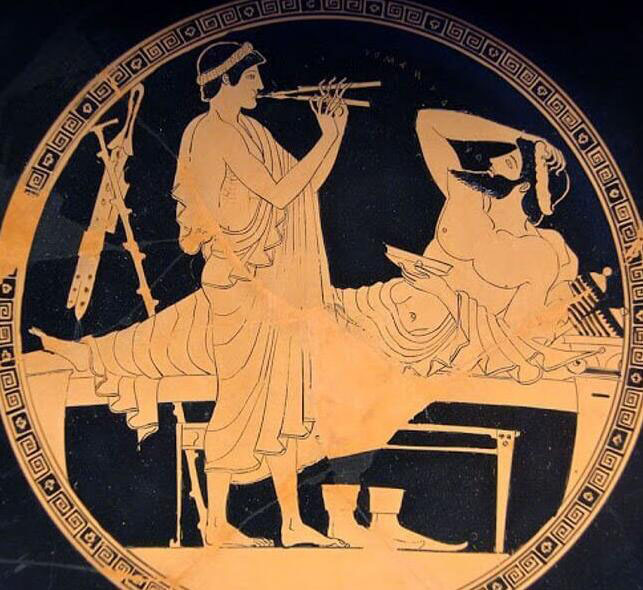

Ancient Greek male prostitute with his male client.

(From the collection of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece)

Fearon recalled from his study that these men who had sex with male prostitutes were called by some “abusers of men.” Those who gave themselves for sexual use, especially to be used sexually as women and used, in other words, to be penetrated like women, were the malakos, meaning “effeminate,” which suggested “to be used like women.”

He was confident from what he’d learned about the Greek words, from the history of Corinth, and who he was as a homosexual, that Paul could not have been writing about homosexuals as he knew them.

“Hmmm,” he thought, “I’m a homosexual, but this is not about me. I know I am a Christian in the kingdom of God. I know God called me to the ministry. I’ve always known God has loved me, even as a child. The translators didn’t get this right. I don’t think ‘homosexuals’ is what Paul meant by these words at all.”

Fearon then checked the translation of the two words as they had appeared in the KJV. There, the two words were translated as: “the effeminate” and “abusers of themselves with mankind.” He thought the KJV translation was far more accurate for these two words separately than the RSV combining Paul’s original two words into one sweeping word.

It seemed clear to Fearon that this RSV translation reflected the prejudice and ignorance of the society in which he had grown up.

He concluded: “My sexuality is part of God’s plan for me and for humanity. I just don’t think they got this right.” He continued to think about the translation. But he couldn’t talk to anyone about it, not even to his professors. The blindness in society at the time to his orientation would expose him.

Writing a letter

Over the span of almost two months, he privately went about constructing a single-spaced three-page letter, with an additional appendix, to send to the publisher of the RSV. He didn’t know if his letter would even be noticed, for he was certain the many Greek scholars around him at the university and so many more throughout the world who had read this Corinthians passage during the past seven years would have noticed this error and written to the publisher as well.

Over the span of almost two months, he privately went about constructing a single-spaced three-page letter, with an additional appendix, to send to the publisher of the RSV.

On Oct. 22, 1959, Fearon sent his five-page letter to Luther A. Weigle. At the end of his impressive academic substantiation of the assumed error in translation, the young seminarian warned:

I write this letter after many months of serious thought and hard work, partly to point out that which to me is a serious weakness in translation, but more because of my deep concern for those who are wronged and slandered by the incorrect usage of this word.

Since this is a holy book of Scripture sacred to the Christian, I am more deeply concerned because well-meaning and sincere, but misinformed and misguided people (those among the clergy not excluded) may use this Revised Standard Version translation of 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 as a sacred weapon, not in fact for the purification of the church, but in fact for injustice against a defenseless minority group which includes the sincere, convicted, spiritually re-born Christian who has discovered himself to be of homosexual inclination from the time of his memory.

I write this letter with certain homosexual individuals in mind — Christians who would die for their faith, their church, and their Lord, but who cannot alter their biological state of being.

I hope the committee responsible for considering any possible corrections or revisions of the RSV text may take my case here presented for consideration.

Weigle responded Nov. 3. He saw the possibility of an error and offered a suggested revision as “those who participate in homosexual vices.”

Fearon responded to Weigle on Nov. 23, 1959, counter-suggesting, “those who practice homosexual vices.” Homosexual vices, as Fearon explained, were akin to same-sex rape. The same-sex sex referred to in 1 Corinthians, he pointed out, was abusive and exploitative in nature, like rape.

The exchange ended on Dec. 3, with Weigle assuring him the letters would be placed in a file and revisited when the team worked on a revision.

An error duplicated

Fearon never thought about the letters again. He could not speak to anyone about them for fear his questioning the translation might point to his sexuality. He did not know his letters were placed in a file, and that, in the next round of translation edits, the team did change “homosexuals” to “sexual perverts,” a term that could be applied to any person, and not to a specific group, homosexuals. The 1971 RSV-r reflects this change.

The creator of The Living Bible added the word “homosexual” in five more places in addition to 1 Corinthians.

However, several other Bible translations already were in the creation process by 1959. None of those translation teams (The Living Bible, The New American Standard Bible, and The New International Version) knew about the admission of error by the RSV team and the intention to revise. All the newer translations used the RSV as the base text. “Homosexual” had become the accepted translation. The creator of The Living Bible added the word “homosexual” in five more places in addition to 1 Corinthians.

Homosexuality soon became a highly charged and useful political wedge issue for the Religious Right. First, the top-selling Bibles all supported the notion of the sinfulness and depravity of homosexuality. Then, the AIDS crisis hit. Romans 1, now including the word “homosexuals,” cemented the Religious Rights’ idea that AIDS was a penalty for sinful behavior.

I knew of this sudden translation shift and included the information in my first book, Walking the Bridgeless Canyon. When I spoke about it in my public presentations, I always added, “I believe this translation shift was the result of cultural and ideological assumptions by men who were born between 1870 and 1917. They knew nothing about what it was to be gay or the meaning of homosexuality as an orientation.”

The letter exchange has been housed in the archives in the Sterling Library at Yale University since 1976, when Weigle died.

Finding the paper trail

Weigle had been the dean of Yale Divinity. In October 2017, I went to Yale University for five days with co-researcher Ed Oxford to see if we could find documentation as to why the RSV team made the decision they did. There was no paper trail that existed for the translation period; it seemed that they made a “logical” uncontested assumption in their translation.

I imagine them looking into the culture of the 1930s, when the work on 1 Corinthians was done, and asking, “What is a simple way to express sex between men that is exploitative, abusive and excessive.” For them, that was homosexuality.

We had found no record of explanation as to their decision anywhere in the almost 100,000 documents we searched, until, on the third day of searching, I found the four-letter exchange between Fearon and Weigle.

We had found no record of explanation as to their decision anywhere in the almost 100,000 documents we searched, until, on the third day of searching, I found the four-letter exchange between Fearon and Weigle.

This set Ed and me on a quest to undo the translation error that had been based on assumptions. For the past four years, I have been writing a book, Forging a Sacred Weapon, which traces the verses used against the LGBTQ community throughout history; it will be out in mid-2023.

The other curiosity was, “Who is this David Sheldon who wrote these crucial letters?” They were written with a P.O. box return address based in Lennoxville, Quebec. We asked my friend Tina Wood to help us find Sheldon. Tina volunteers to help adoptees, birth families and others searching for family and friends.

The details of her search (also told in the book) are head-spinning. How do you find a person who wrote a series of letters 60 years ago with a P.O. box as the return address? (We did not know at the time that Fearon was using his first and middle name, not his last name.) It took almost a year, but Tina found him.

On Aug. 17, 2018, I called Fearon and asked him if he had written letters questioning the RSV translation team in 1959.

“Yes,” came his reply.

I had suspected on first reading the letters that the author was gay. Fearon confirmed he was.

“When did you come out?” I asked.

“Never. I never came out,” he replied. He was 80 years old.

He was partnered with Joe for 23 of those years. People thought live-in Joe was his cousin.

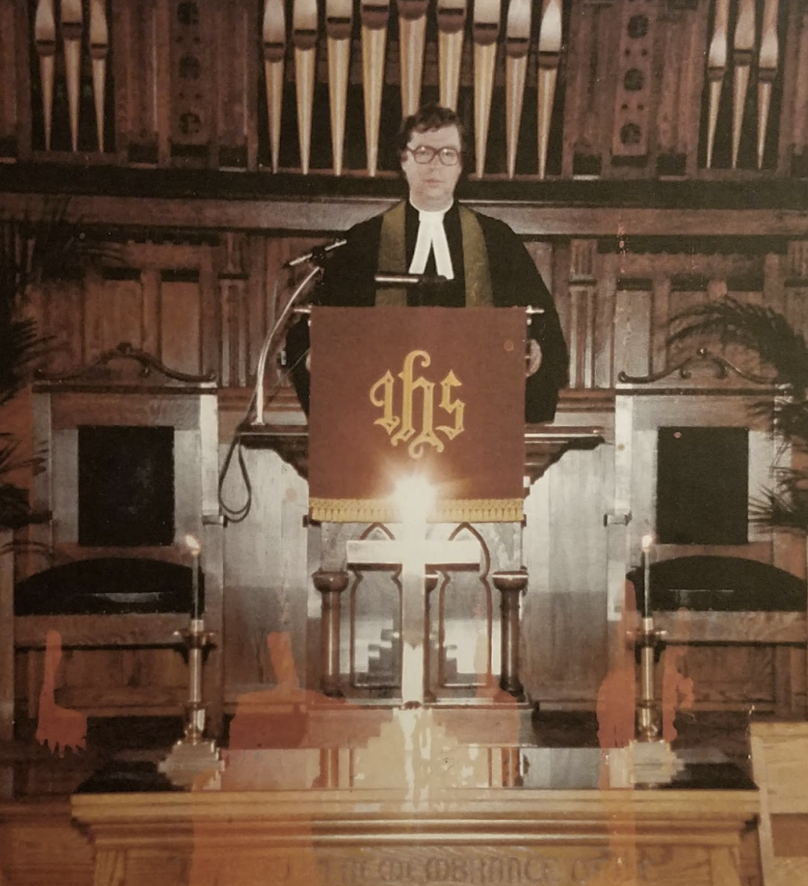

Fearon became a minister in the United Church of Canada after his studies at McGill. He served in nine pastorates for over 37 years. He was partnered with Joe for 23 of those years. People thought live-in Joe was his cousin.

The only such letters

Fearon’s letters left a historical record of why the RSV translation team made their long-reaching and damaging decision.

There is no other documentation explaining why the team included the word “homosexual” in the Bible, except the information found in the Fearon-Weigle letters.

Fearon had yet to learn he impacted the 1971 revision change. He noticed the shift to “sex perverts” in the revision. When I shared the information with him in our first of dozens of long phone calls, he was surprised his letters had moved Weigle to reassess his assumptions. Fearon always imagined his letters were “one of hundreds, if not thousands” written objecting to the translation.

In fact, Fearon’s was the only such letter.

I began presenting these findings in public presentations starting in 2018. At one such presentation at Hollywood United Methodist Church, filmmaker Rocky Roggio brought her pastor father along.

Sal Roggio believes homosexuality is a sin. Rocky was planning on doing a documentary examining her relationship with her father. However, after listening to the presentation, Rocky switched courses. Over the past four years, she produced an excellent documentary, 1946: The Mistranslation that Shifted a Culture.

1946 threads several stories together: Rocky and Sal, my research work with Ed, Fearon’s letters, and his story, and all supported by interviews with expert Old and New Testament scholars. The film is going through film festival now and will likely end up with a major online streamer within the next year.

Fearon died last week peacefully in his home in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island. He was discovered Jan. 8 by a friend who requested a wellness check. He was slumped over at his dining room table, his glass of beer half-finished, his television on, and his eyeglasses only slightly askew.

I would like to imagine he was watching the news, and God said, “Hey, David, good and faithful servant, you’ve done your work. It’s time.”

Fearon did not know the legacy he would leave when, at age 21, he bravely challenged the RSV translation error. His recently discovered letters left a record that allow us to further academically challenge a grave translation error based on wrong assumptions.

In the last few years, he often said, “I used to think God called me to pastoral ministry despite my being gay. I’ve decided he called me to ministry because I am gay.”

Watch an interview with David here.

Kathy Baldock lives in Reno, Nev., where she is a researcher, author and LGBTQ ally. Her forthcoming book is Forging a Sacred Weapon: How the Bible became Anti-Gay.

Related articles:

My quest to find the word ‘homosexual’ in the Bible | Opinion by Ed Oxford

After 30 years, the NRSV gets an update: Here’s what that means