To learn more about religion, just ask an atheist.

That’s one takeaway from a recent Pew Research Center survey that asked Americans multiple-choice questions about religion.

Respondents also were asked about their own faith traditions – and were rivaled by atheists there, as well.

But that comes as little surprise to scholars who study and teach about American religion.

“With atheists and agnostics, my initial guess its an education effect,” said Paul Froese, a sociology professor and director of Baylor University’s Survey of Religion. “On average, they tend to have more education.”

Paul Froese

And that makes them more likely to be studious on matters of faith, he said.

Nor is it shocking that Christians aren’t particularly well versed about Christianity. That’s to be expected in a nation where overall religious literacy is low.

Froese said that’s been evident for a time and well documented in the 2007 book Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know – and Doesn’t, by Stephen Prothero.

“People don’t tend to know a lot about other religions, and they don’t tend to know much about their own religion, either,” Froese said.

Atheists most knowledgeable

The tale is in the numbers.

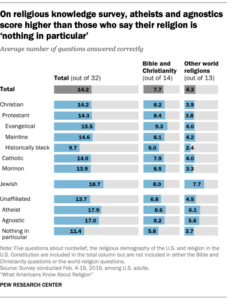

Pew reported that atheists and agnostics, respectively, answered an average of 17.9 and 17 questions correctly, out of 32. The only group to score better overall were Jewish Americans at 18.7, Pew reported.

Evangelical Christians were next with an average of 15.5 correct answers, followed by Mainline Protestants at 14.6 and Catholics with 14.

Atheists – at 55 percent – also led the way when asked if they know there is “no religious test” required by the Constitution for to hold office.

Agnostics were next at 41 percent, followed by Jewish respondents at 38 percent. Pew said 27 percent of mainline Christians answered correctly.

Among the lowest scorers on that question were evangelicals and historically black Christians, at 22 and 15 percent respectively, according to Pew.

But 33 percent of those who identify as “unaffiliated” answered that question correctly.

Understanding “where the lines are”

Atheists and Jews and other minority groups are often up-to-speed on other people’s religions because they have to be, said Robert Nash, professor of missions and world religions at Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology.

Religious minorities around the world are highly motivated to learn about the dominant faiths in their settings to either avoid or deal with persecution, he said.

“You have to understand where the lines are.”

Examples of that include Muslims in the United States and Christians in the Middle East.

“Christians in Syria are probably much more in touch with Islam than Muslims in Syria are in touch with Christianity,” Nash said.

Jewish communities have been at this for centuries because they have always been tiny fraction of the world’s population.

“They have to know the dominant culture and other religions wherever they may find themselves,” he said.

Trouble finding Matthew

The Pew survey also focused on knowledge about the Bible and Christianity.

Here, evangelicals led the way with an average of 9.3 questions out of 14 answered correctly, Pew said. Other top scorers were atheists at 8.6, Latter-day Saints at 8.5, mainline Christians at 8.1 and Jewish respondents with 8.0.

The numbers reflect realities that ministers and religion professors have been tracking for decades.

“Twenty-five years ago, I could ask my students in class to open the Bible and find the Gospel of Matthew. More could find it then than can find it today,” said Glenn Jonas, professor of religion at Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina.

Glenn Jonas

Jonas, who has also served local congregations as an interim pastor, said there could be more knowledge in the pews about church and denominational history.

“You can’t take for granted that the typical Baptist, the typical Presbyterian or the typical Lutheran lay person will know anything about their own traditions,” he said.

Nor do many he encounters have much of an understanding of other faiths. But it should be a priority.

“Religious literacy is important in helping us understand the world and, in American society, to navigate through so many of the ethical arguments going in society right now,” he said.